ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

EMBROIDERY AND OTHER MATERIAL CULTURE

– in the Årsta Diary 1793 to 1839

Märta Helena Reenstierna (1753-1841) lived most of her life at Årsta manor house close to Stockholm, and for over forty years, she wrote a diary known as the Årsta Diary (Årstadagboken). She started the diary first at the age of 40 in 1793, after a childbearing period when seven of her eight children tragically died before reaching adulthood. Several abridged Swedish editions of her diary have been published over the years, together with audiobooks, a few in-depth publications, book chapters, and journal articles on various aspects of her writing. This essay aims to increase the understanding within an English reading audience for this relatively unknown document from an international perspective. Primarily focusing on her interest in embroidery fitted into her responsibilities and everyday tasks in the manor house.

The only known portrait of Märta Helena Reenstierna is this miniature, with an engraving giving the date to 13 November in 1796 – that is to say about three years after she started to write her diary. According to information on the museum catalogue card, the ring was a present to her husband Christian Henrik von Schnell, whilst the gold ring had been made by the jeweller Nils Hoffsten in Stockholm. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum. No: NMA.0059486).

The only known portrait of Märta Helena Reenstierna is this miniature, with an engraving giving the date to 13 November in 1796 – that is to say about three years after she started to write her diary. According to information on the museum catalogue card, the ring was a present to her husband Christian Henrik von Schnell, whilst the gold ring had been made by the jeweller Nils Hoffsten in Stockholm. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum. No: NMA.0059486). Embroidery for various needs of the family was mentioned every now and then in the diary, but even so had a continuation over the years. Whilst the necessity to decide about and purchase new fabrics, be in contact with tailors and seamstresses, keep an eye on ongoing laundry tasks, darning or remaking of clothes, financial realities linked to clothing as well as her own sewing being a much more substantial material in her diary – which has been researched by fashion historian Pernilla Rasmussen (2010: pp. 106-122). These matters will not be dealt with further in this essay, but it may be noted that Märta Helena, throughout her life, seems to have had a genuine interest in fashion, which to some extent included embroidery. The diary also reveals a multitude of details about the employees in the manor house and her role as the mistress of the household, keeping a close eye on domestic economies. The consumption of textiles never appears to have been excessive, even if the family’s standard of living was comfortable, and Märta Helena was able to live throughout her long life after the standards she was used to with an active social life, mainly in bourgeoise circles of the Stockholm area but also within the lower nobility.

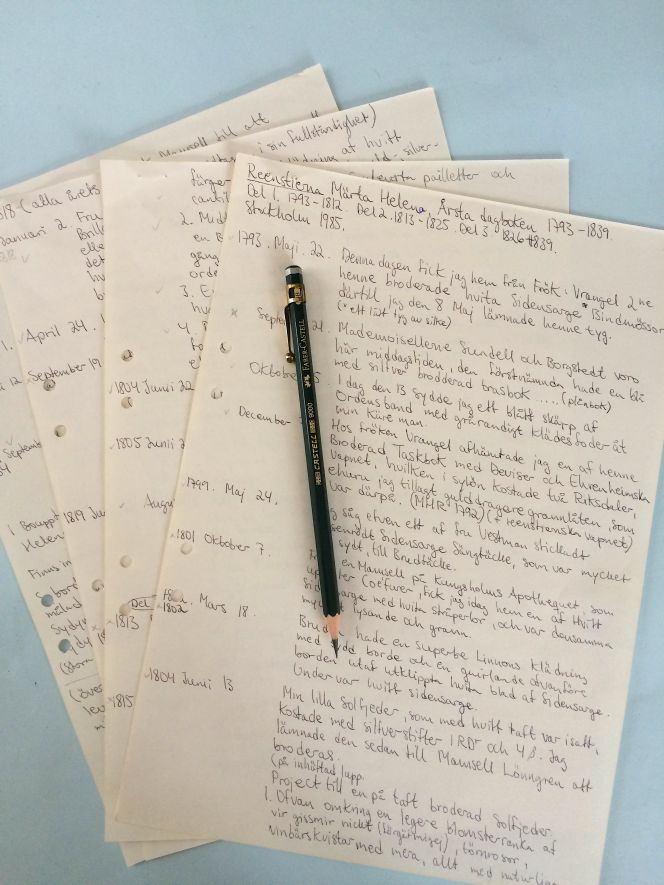

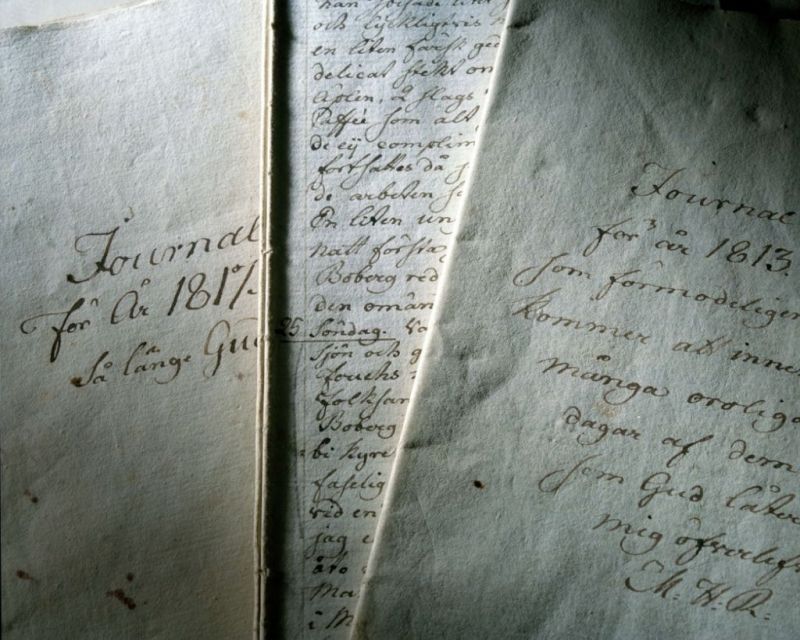

The diary from 1793 to 1839 consists of circa 5000 folio pages, whereof only parts have been published. The handwriting is overall careful and clearly readable, but to minimise handling of the document, the Nordic Museum Library additionally keeps a machine written copy of the Årstad Diary (Årstadagboken). (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum Archive. No: NMA.0034852).

The diary from 1793 to 1839 consists of circa 5000 folio pages, whereof only parts have been published. The handwriting is overall careful and clearly readable, but to minimise handling of the document, the Nordic Museum Library additionally keeps a machine written copy of the Årstad Diary (Årstadagboken). (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum Archive. No: NMA.0034852).Some enlightening examples about her ongoing textile work from the years 1793 to 1834 give glimpses into her daily life, craft skills, design ideas, ordering of silk embroideries, materials used as well as to her own desired objects used in luxury and everyday garments and accessories.

- 22 May 1793. ‘This day, I received from Miss Wrangel two of her embroidered white caps of silk serge, for which I had given her fabric on 8 May.’

- 15 October 1793. ‘Today, I stitched a blue belt of a ribbon of an order with a grey striped broadcloth lining to my dear husband.’

- 7 December 1793. ‘At Miss Wrangel’s, I collected one of her embroidered pocket-books with devices and the Ehrenheim coat of arms, which in sewing charges came to 2 rixdollar, even if I had added the beautiful golden [thread] on display (MHR 1792 and the Reenstjierna coat of arms)’.

The aristocratic unmarried Miss Wrangel was well known for her embroidery skills among the well-to-do in Stockholm at this time, a handicraft expertise which gave her an additional income (Ilmakunnas: p. 316) – evident also in the diary entries above.

Some years later, Märta Helena admired an embroidery made by another lady in her circle of friends: ‘I also saw one of Mrs Vestman’s rose-red silk serge bedcovers, which was sent and very finely stitched – for a wedding bedcover.’ (24 May 1799). It is overall my impression, after an in-depth study of the diary, that Märta Helena did not make delicate silk embroidery herself. However, it seems not to have been due to lack of time; instead, she preferred other textile handicrafts or to socialise with relatives and friends in her spare time. Reasons may also have been that she had no specialist knowledge in fine embroidering or too poor eyesight, at the same time as she appears to have aimed for a high level of perfection. On the other hand, she had very specific wishes for design, materials and colours, which was explained in the diary on 13 June 1804 and at an added note about a project idea: ‘My small fan, which was made of white taffeta, came to 1 rixdollar and 4 öre including pins of silver. I thereafter handed it over to Miss Lönngren to be embroidered.’

‘Project for one on taffeta embroidered fan.

- Above a flower creeper of forget-me-not, roses, currant bush twigs etc, all with natural colours and sorts of coloured spangles and braids.

- Centred, a larger medallion, which should depict an arbour or green trees forming a covered path; between the trees, there will be a curved shape whereupon one can read the word la Solitude.

- A smaller oval on one side of the larger, within a coat of arms, is embroidered in black thread only.

- On the other side, a similar sized oval, where a flying bird seems to hold in its beak a note or devise with the letters MHR [Märta Helena Reenstierna].’

Already nine days later, on 22 June 1804, she wrote: ‘From Miss Lönngren, I now received my small fan, embroidered with roses, silver- and red spangles.’

![This map over Stockholm drawn in the earliest years of the century (printed 1805), demonstrates how close to the capital the Reenstierna family lived, useful for shopping, selling kitchen garden produce of the manor house, visiting friends or the theatre alike. Please notice that Årsta manor house was situated on the south side of ‘Årsta Wiken’ at the bottom left of the map. Occurrences linked to embroidery and travels as mentioned in her diary from the same period is enlightening. Initially on 27 June in 1805: ‘Today I drew a motif, which I think should be lovely to embroider after, with coloured threads on white silk serge for a small parasol.’ Probably this design was sent to the chosen skilled embroiderer, because about six weeks later, on 8 August the diary entry reads: ‘The afternoon was glorious and pleasant, when I with chaise travelled to the city to Mrs Hultner [dressmaker and embroiderer] due to pay the great expense for the satin stitching, which adorned an ell of white silk serge, intended for a small parasol, and for which she charges 6 rixdollar. I left the fabric to parasol maker Backmanson’. (Courtesy of: Military Archive in Stockholm. Map of Stockholm in 1802-1803 by Carl Akrel).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/3-1280px-map_stockholm_akrel_1802_stockholm_277a-800x519.png) This map over Stockholm drawn in the earliest years of the century (printed 1805), demonstrates how close to the capital the Reenstierna family lived, useful for shopping, selling kitchen garden produce of the manor house, visiting friends or the theatre alike. Please notice that Årsta manor house was situated on the south side of ‘Årsta Wiken’ at the bottom left of the map. Occurrences linked to embroidery and travels as mentioned in her diary from the same period is enlightening. Initially on 27 June in 1805: ‘Today I drew a motif, which I think should be lovely to embroider after, with coloured threads on white silk serge for a small parasol.’ Probably this design was sent to the chosen skilled embroiderer, because about six weeks later, on 8 August the diary entry reads: ‘The afternoon was glorious and pleasant, when I with chaise travelled to the city to Mrs Hultner [dressmaker and embroiderer] due to pay the great expense for the satin stitching, which adorned an ell of white silk serge, intended for a small parasol, and for which she charges 6 rixdollar. I left the fabric to parasol maker Backmanson’. (Courtesy of: Military Archive in Stockholm. Map of Stockholm in 1802-1803 by Carl Akrel).

This map over Stockholm drawn in the earliest years of the century (printed 1805), demonstrates how close to the capital the Reenstierna family lived, useful for shopping, selling kitchen garden produce of the manor house, visiting friends or the theatre alike. Please notice that Årsta manor house was situated on the south side of ‘Årsta Wiken’ at the bottom left of the map. Occurrences linked to embroidery and travels as mentioned in her diary from the same period is enlightening. Initially on 27 June in 1805: ‘Today I drew a motif, which I think should be lovely to embroider after, with coloured threads on white silk serge for a small parasol.’ Probably this design was sent to the chosen skilled embroiderer, because about six weeks later, on 8 August the diary entry reads: ‘The afternoon was glorious and pleasant, when I with chaise travelled to the city to Mrs Hultner [dressmaker and embroiderer] due to pay the great expense for the satin stitching, which adorned an ell of white silk serge, intended for a small parasol, and for which she charges 6 rixdollar. I left the fabric to parasol maker Backmanson’. (Courtesy of: Military Archive in Stockholm. Map of Stockholm in 1802-1803 by Carl Akrel).Some notes in the diary from Märta Helena’s older years, between 1818 and 1834, give further ideas of her ongoing interest in embroidery and willingness to pay quite extensive sums for fashionable garments as well as being nostalgic and planning for her own demise.

- 2 January 1818. ‘Mrs Grak had with her a Christening gown of white Brillantin [a sort of muslin, including gold, silver and silk threads, which add an effect to the pattern and make it shine] with a raised embroidered tulle decoration and where on I put rose red silk serge ribbons’.

- 24 April 1818. ‘Today I have sewn with Turkish [red] yarn, in the afternoon, marked four pairs of socks.’

- 23 June 1819. ‘Miss Wilhelmina Vesterstråle had sewn a Bonnett Negligée [morning cap] for me, as I intend to use as a funeral cap when God call me unto Himself. I therefore sent her 3 rixdollar on 23 March. She had sent the cap to my sister-in-law, which further enriched the same, as it was quite beautifully and finely embroidered and decorated with a scalloped piece of tulle around it.’ It is more than understandable that she felt old at this time when having outlived her husband and all eight children, but Märta Helena came to live for another twenty years, up to the old age of 87. Her social life, however, continued up to her 70s and 80s:

- 31 July 1828. ‘Carl Reenstierna with wife and daughter arrived for dinner – the last mentioned presented me with a rather fine embroidered small tulle collar’.

- 12 July 1830. ‘Mrs Molzer, who had been kind enough to choose a black gauzy veil, called Voile in French – sent such a one, of embroidered tulle, for 24 rixdollar. I considered this an extensive foolish expense – but paid in cash.’

- 24 September 1834. ‘Mrs Leufstedt visited for a while – we entertained ourselves by looking at – a pair of 200-year-old embroidered wedding shoes and my soon sixty-years-old wedding shoes and wedding slippers, etc.’

This well-preserved cap was part of the Christening costume for Märta Helena Reenstierna’s and Christian Henrik von Schnell’s children being born between 1776 and 1787. This small garment just as the second cap below, must have been very sentimental objects for Märta Helena and her husband as seven of the eight children died when young. Probably being kept in a chest or drawer, for best safekeeping. Judging by the diary introduced first in 1793, such a delicate garment seems not to have been made by the young mother herself, but instead by several craft skilled individuals. Maybe she choose the fabric etc, assisted by a seamstress who stitched the fine cap of silk brocade with a cotton lining and attached red silk ribbons. The gold metallic bobbin lace was probably of French origin and purchased from a shop in Stockholm. This assumption is strengthened by that the rigorous sumptuary laws from 1766 was revoked by Gustav III during his reign from 1772 to 1792 – a period when all sorts of imported luxury goods became immensely popular in the well-to-do strata of society. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum. No: NM.0000638).

This well-preserved cap was part of the Christening costume for Märta Helena Reenstierna’s and Christian Henrik von Schnell’s children being born between 1776 and 1787. This small garment just as the second cap below, must have been very sentimental objects for Märta Helena and her husband as seven of the eight children died when young. Probably being kept in a chest or drawer, for best safekeeping. Judging by the diary introduced first in 1793, such a delicate garment seems not to have been made by the young mother herself, but instead by several craft skilled individuals. Maybe she choose the fabric etc, assisted by a seamstress who stitched the fine cap of silk brocade with a cotton lining and attached red silk ribbons. The gold metallic bobbin lace was probably of French origin and purchased from a shop in Stockholm. This assumption is strengthened by that the rigorous sumptuary laws from 1766 was revoked by Gustav III during his reign from 1772 to 1792 – a period when all sorts of imported luxury goods became immensely popular in the well-to-do strata of society. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum. No: NM.0000638).  This somewhat plainer Christening cap in just as good a condition, is the second such baby garment used in the Reenstierna family during the 1770s and 1780s. One may speculate if this one was intended for the boys and the more colourful one above for the girls! However, the design being similar and lined with a fine cotton quality, but a silk brocade was chosen for the top part only, whilst a plain white silk fabric was used for the side parts of the cap. The exquisite silver metallic bobbin lace being the main feature together with white silk ribbons to tie under the cheek. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum. No: NM.0000639).

This somewhat plainer Christening cap in just as good a condition, is the second such baby garment used in the Reenstierna family during the 1770s and 1780s. One may speculate if this one was intended for the boys and the more colourful one above for the girls! However, the design being similar and lined with a fine cotton quality, but a silk brocade was chosen for the top part only, whilst a plain white silk fabric was used for the side parts of the cap. The exquisite silver metallic bobbin lace being the main feature together with white silk ribbons to tie under the cheek. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum. No: NM.0000639).As a note of conclusion, Märta Helena Reenstierna’s estate inventory, dating 24 February 1841, listed substantial numbers of cloth, yarn and thread of various qualities. The document lacked any details about embroidery on furnishing textiles or clothes, but a few necessary tools were included, which she must have used over the years: 1 Sewing-table, 1 Painted wooden box with eight needle holders, 1 Sewing pad fastened with a screw & 1 Sewing pad with a lead weight.

Notice: All quotes from (Reenstierna, Märta Helena, Årstadagboken…) and the estate inventory (1841) have been translated from Swedish to English via the edition printed in 1985.

Sources:

- Ilmakunnas, Johanna, ‘Embroidering women and turning men – Handiwork, gender, and emotions in Sweden and Finland, c. 1720–1820’, Scandinavian Journal of History, 41:3, 306-331, 2016.

- Military Archives in Stockholm, Sweden (map of Stockholm 1805, digital source).

- Rasmussen, Pernilla, Skräddaren, sömmerskan och modet – Arbetsmetoder och arbetsdelning i tillverkningen av kvinnlig dräkt 1770-1830, Stockholm 2010 (pp. 106-122).

- Reenstierna, Märta Helena, Årstadagboken: journaler från åren 1793-1839, del 1-3, ed. Gunnar Broman and Sigurd Erixon, Stockholm 1985.

- Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon, Band 29, p. 724 – ‘Märtha Helena Reenstjerna’ (Author: Christina Sjöblad), 1995-1997.

- The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden (Digitalt museum: Four photographs & information about the historical links to Märta Helena Reenstierna on the catalogue cards).

iTEXTILIS | LOCATION | Notes written in the late 1980s

The idea for this essay came to light when I recently looked through my old textile archive and found these quotes about embroidery from the Årsta Diary – dating 1793 to 1839 – made more than thirty years ago. Historical embroidery has been one of my main interests and research subjects over the years, also including reconstructions of various designs and techniques. Additionally, present-day free available digitised images from many museum collections, like the objects linked to Märta Helena Reenstierna in this essay, give new possibilities to present historical textiles.

V H

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE