ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

HANS SLOANE’S COLLECTION

– An 18th Century Study of Natural Curiosities and Textile Dyes

In 1748, the naturalist Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) visited the famous collection of the elderly physician Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) in Chelsea, London. Kalm’s journal observations reveal details of a very substantial collection, including the interest in other cultures via descriptions of clothing and natural dyes. It also has to be pointed out that the 18th century European travellers’ various ways of studying Indigenous peoples have to be seen in the context of the time – slavery, women’s position in society, the Europeans versus people of other cultures and curiosity. This essay will focus on personal belongings and collections from 18th-century travels, with notes and images linked to Sloane. Foremost natural red dyes – like cochineal and madder – from his travel to Jamaica, among other islands in his youth, and the Chelsea Physic Garden, together with some thoughts on his global natural history network, female scientific illustrators and early museums.

Line engraving of Hans Sloane by W. H. Lizars after T. Murray in 1722 or about twenty-five years before Pehr Kalm visited Sloane’s collection. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Images, No: V0005467ER).

Line engraving of Hans Sloane by W. H. Lizars after T. Murray in 1722 or about twenty-five years before Pehr Kalm visited Sloane’s collection. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Images, No: V0005467ER).The naturalist Pehr Kalm, who stayed in London and the surrounding counties for circa half a year on his way to the North American colonies along the East Coast, was one of many visitors to the well-known collection of Hans Sloane in Chelsea. In April and May of 1748, he made several visits according to his travel journal. Finally, on May 26th, he listed an extensive number of items from the Sloane collection, including descriptions of minerals, some ethnographical curiosities and natural history objects. The listing had few brief details of a textile nature and may even be regarded somewhat in the “outskirts of textiles”, occasionally only giving a hint about such materials.

- ‘An adult Chinese lady’s shoes, though no larger than the shoes of children 2 or 3 years old among us.

- Various dresses of Indian women.

- Bark of a tree from Jamaica, which was said to be called ‘Ligoto’, of which some exactly resembled a piece of white chamois; some pieces of it resembled linen or paper; some pieces resembled light muslin or cambric, and they were said to have been used for cuffs.

- The shoes of various nations; but the birch-bark shoes of the Finns and the bast shoes of the Russians were lacking here.

- In another room we were shown an Egyptian mummy, all kinds of anatomical praeparata, human sceleta etc.

- Another room with various kinds of leather and other forms of clothing of strange peoples; in the same room also a stuffed camel.’

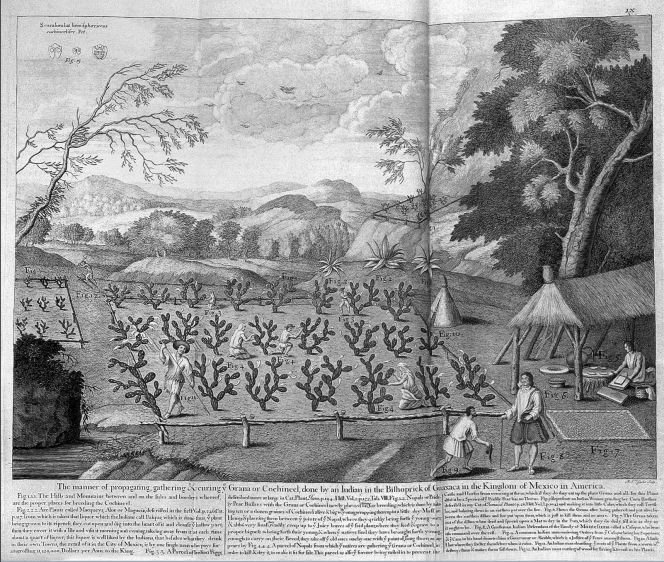

In Kalm’s observations of the collection in Chelsea – cochineal was not listed. However, this very informative and detailed image from Sloane’s publication – ‘A voyage to the islands, Madeira, Barbados, Nieves, St. Christophers and Jamaica with the natural history of the herbs and trees…’ (1707, 1725) – demonstrates Sloane’s interest in the desirable red dyestuff in a plantation in Mexico. Additionally, Kalm made notations on cochineal in other contexts, during his stay in the North American colonies from 1748 to 1751 (Courtesy of: Wellcome Images, No: EPB 48545/D VOL. 2).

In Kalm’s observations of the collection in Chelsea – cochineal was not listed. However, this very informative and detailed image from Sloane’s publication – ‘A voyage to the islands, Madeira, Barbados, Nieves, St. Christophers and Jamaica with the natural history of the herbs and trees…’ (1707, 1725) – demonstrates Sloane’s interest in the desirable red dyestuff in a plantation in Mexico. Additionally, Kalm made notations on cochineal in other contexts, during his stay in the North American colonies from 1748 to 1751 (Courtesy of: Wellcome Images, No: EPB 48545/D VOL. 2).Pehr Kalm was a former student of Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) in Uppsala, Sweden and was regarded as one of Linnaeus’ seventeen so-called Apostles who all travelled outside Europe for the purpose of science, collecting natural history specimens, discovering new plants from a European perspective etc. Except for Linnaeus, he was the only one in the group who met Hans Sloane in person. However, a few of the others – Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805), Anders Sparrman (1748-1820) and Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) – mentioned Sloane’s collection or referred to his work in their journals during the period 1750s-1770s.

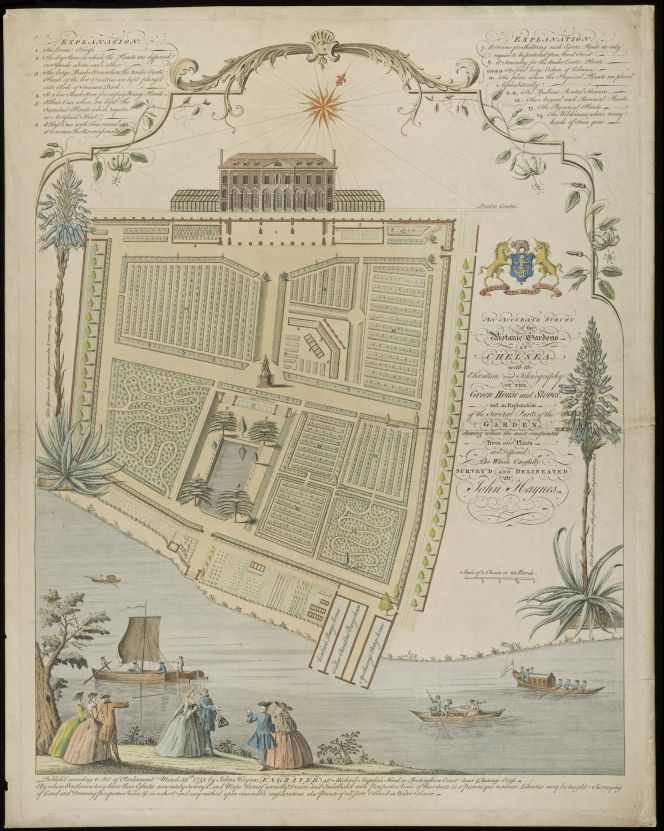

A detailed and beautiful view of ‘The Physic Garden, Chelsea: a plan view. Engraving by John Haynes, 1751’. The plan gives an impression of wealthy visitors to the garden, dressed in the latest fashion. Furthermore, this depiction was made just a few years after Pehr Kalm’s visit to Hans Sloane, who since 1713 had been the owner of the manor house in picture. Kalm was one of numerous naturalists, botanists and other individuals of the time, who were associated with the garden and its wide range of native and non-native plants. One such plant for natural dyeing of yarn and fabric was the useful madder (Rubia tinctorum) for hardy red colours, as informed by the chief gardener Philip Miller (1691-1771) of Chelsea Physic Garden in his book published in 1758. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Images, No: Iconographic Collection 662588i).

A detailed and beautiful view of ‘The Physic Garden, Chelsea: a plan view. Engraving by John Haynes, 1751’. The plan gives an impression of wealthy visitors to the garden, dressed in the latest fashion. Furthermore, this depiction was made just a few years after Pehr Kalm’s visit to Hans Sloane, who since 1713 had been the owner of the manor house in picture. Kalm was one of numerous naturalists, botanists and other individuals of the time, who were associated with the garden and its wide range of native and non-native plants. One such plant for natural dyeing of yarn and fabric was the useful madder (Rubia tinctorum) for hardy red colours, as informed by the chief gardener Philip Miller (1691-1771) of Chelsea Physic Garden in his book published in 1758. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Images, No: Iconographic Collection 662588i).Interestingly, Pehr Kalm’s journal on April 28th 1748 mentioned the significance of Sloane’s collection and gave some thoughts about its future destiny:

‘We were exhausted by looking at all these rarities and were obliged to acknowledge that up to the present day no private individual in the world, merely from what he has collected in his lifetime, is likely to more than half-way match what Sir Hans Sloane possesses, who, apart from what has been presented to him, has used more than 100,000 pounds sterling to buy these natural history specimens and rarities; and he is now said to wish to sell it to some public collection for 30,000 p. st., disregarding the fact that he would thereby lose 70,000 p. st., if only his collection may be kept together after his death.’

A few years later, after Sloane’s death, the continuing history and importance of the collection have been described as follows by the British Museum:

‘A physician by trade, Sir Hans Sloane was also a collector of objects from around the world. By his death in 1753 he had collected over 71,000 objects. Sloane bequeathed his collection to the nation in his will and it became the founding collection of the British Museum.’

Overall, Hans Sloane had an extensive net of friends and colleagues during his long life; many associated with him via the natural sciences and some of these individuals are linked to my ongoing project about 18th century naturalists: Kalm (1748) and Linnaeus (1736 & correspondence) were two of these naturalists, who both – with twelve years apart – had made visits to Sloane. Together with ten further individuals out of the hundred in the studied “Linnaean network”, which have been possible to trace to Sloane. Either via personal meetings/long-term professional contacts in London or via correspondence:

- Peter Artedi (1705-1735): Swedish naturalist – stayed at least eight months in London around 1732-33.

- John Bartram (1699-1777): botanist in the Philadelphia area – correspondence only.

- Johannes Burman (1706-1779): Dutch botanist and physician – correspondence only.

- Abraham Bäck (1713-1795): Swedish physician – who visited London and Sloane’s museum in 1742.

- Mark Catesby (1682-1749): English naturalist – in person and correspondence.

- Peter Collinson (1694-1768): gardener in London & trader of plants – in person and correspondence.

- Johann Jacob Dillenius (1684-1747): German botanist, moved to Oxford – in person and correspondence.

- George Edwards (1694-1773): English naturalist and ornithologist – in person and correspondence.

- Philip Miller (1691-1771): English botanist and gardener at Chelsea Physic Garden – in person.

- Albertus Seba (1665-1736): Dutch collector, pharmacist and zoologist – correspondence only.

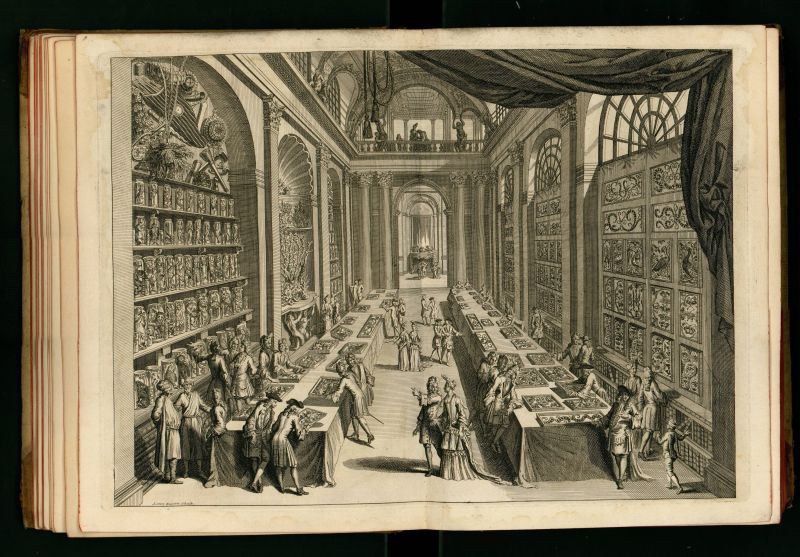

As an example of Sloanes further networking, an image from the Dutch textile merchant and collector Levinus Vincent’s (1658-1727) cabinet of curiosities is enlightening in more than one way. Over many years, Levinus had designed and collected a great variety of natural history and ethnographical objects for this cabinet – assisted by his wife Joanna van Breda (16?-1715). The collection was a main attraction for wealthy individuals in the Dutch Republic and foreign visitors alike, aiming to show scientific symmetry, harmony and aesthetic ordering of Nature. Judging by this detailed depiction from circa 1705, the “museum” was displayed in magnificent settings in Harlem, with selected boxes placed on long tables covered with linen cloths – including desirable “exotic” objects purchased, bartered, looted or maybe just collected for free from far-flung countries, whilst the weaving of linen cloth was a domestic speciality of the Dutch. There is no evidence for that Hans Sloane visited the cabinet and he and Levinus had slightly different approaches/professions to natural history and textile materials, but even so correspondence linking the two men are still extant. (From: Vincent Levinus, Wondertooneel der natuur…frontispiece, Harlem 1715. Wikimedia Commons).

As an example of Sloanes further networking, an image from the Dutch textile merchant and collector Levinus Vincent’s (1658-1727) cabinet of curiosities is enlightening in more than one way. Over many years, Levinus had designed and collected a great variety of natural history and ethnographical objects for this cabinet – assisted by his wife Joanna van Breda (16?-1715). The collection was a main attraction for wealthy individuals in the Dutch Republic and foreign visitors alike, aiming to show scientific symmetry, harmony and aesthetic ordering of Nature. Judging by this detailed depiction from circa 1705, the “museum” was displayed in magnificent settings in Harlem, with selected boxes placed on long tables covered with linen cloths – including desirable “exotic” objects purchased, bartered, looted or maybe just collected for free from far-flung countries, whilst the weaving of linen cloth was a domestic speciality of the Dutch. There is no evidence for that Hans Sloane visited the cabinet and he and Levinus had slightly different approaches/professions to natural history and textile materials, but even so correspondence linking the two men are still extant. (From: Vincent Levinus, Wondertooneel der natuur…frontispiece, Harlem 1715. Wikimedia Commons).To what extent women took part in natural history work in the 18th century is often a debatable question, owing to a multitude of reasons at this time. Strictly limited access to education within this field was the main obstacle, with the exception of botany – like collecting plants, keeping a herbarium or being a botanical artist – which to some degree was accepted. Other limitations being pure social norms or moral traditions or motherhood over an extended period of time. Another aspect is that even if coming from a well-to-do background, women were less able to write than men, which further reduced the traces of any possible former involvement in natural science activities linked to letters, pamphlets or books of their hand. Even so, in some contemporary depictions of cabinets of curiosities, early museums or botanical gardens, wealthy female visitors visibly took an active interest in natural sciences from several perspectives, equally as women evidently worked as artists/scientific illustrators. Particularly notable was the botanical and zoological illustrator Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717) – a predecessor to most naturalists in the Linnaean network – whose life and legacy have frequently been researched in recent decades. However, she was famous already during the 18th century for her skilfully made as well as minutely accurate drawings of plants and insects, which in this context is an interesting link to Hans Sloane, due to that his extensive collection included watercolour drawings of her hand. One of these large-size albums of Merian’s watercolour drawings is on display in The Enlightenment Gallery at the British Museum – together with other rare objects from Sloane’s original collection.

Sources:

- British Museum, London, United Kingdom. (Research visit at The Enlightenment Gallery, January 2020. & Museum website source: Sir Hans Sloane and his collection & quote).

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, Volume Three, Book One & Two (Pehr Kalm’s journal), London & Whitby 2008.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (Pehr Kalm’s chapter. pp. 31-60).

- Kalm, Pehr, Travels into North America, three vols. Vol. 1: Warrington 1770 & Vol. 2-3: London 1771.

- Kalm, Pehr, Resejournal över resan till Norra Amerika. Published by Martti Kerkkkonen & John E. Roos, Helsingfors, first vol. 1966 & second vol. 1970.

- Miller, Philip, The method of cultivating madder, as it is now practised by the Dutch in Zealand…, London 1758.

- Roemer, Bert van de, ‘Redressing the Balance: Levinus Vincent’s Wonder Theatre of Nature’, Public Domain Review (Online: 2014/08/20).

- Skottsberg, Carl, Pehr Kalm – Levnadsteckning, Stockholm 1951.

- Sloane, Hans, A voyage to the islands, Madeira, Barbados, Nieves, St. Christophers and Jamaica with the natural history of the herbs and trees…, two volumes. London 1707, 1725.

- The Linnaean Correspondence (Studies of a large selection of letters, to and from individuals in the Linnaean network). Online resource, Alvin.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE