ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

INDIGO BLUE CLOTHES

– A European Perspective on East India Voyages: 1740s to 1770s

Most years of the Swedish naval officer Carl Fredrich von Schantz’s (1727-1792) life are relatively unknown – a married man with three children who reached adulthood – but a period in his youth (from 1746 to 1749) is an exception due to a preserved handwritten journal of his hand. This written account has inserted watercolour plates, some of which include local men dressed in indigo blue on Java and Canton (Guangzhou). The illustrations reveal informative observations of everyday life as he saw it at the time on an East India voyage. The vividly illustrated blue garments used in the local communities can also be compared to a selection of contemporary written descriptions of blue textile dyes and a few other traditionally used dye plants, carefully examined and recorded in travel journals by three of Carl Linnaeus’ Apostles. They travelled with the Swedish East India Company around the same time, whilst one of them worked for the Dutch East India Company in the 1770s. These linked primary sources will be examined more closely in this essay to put von Schantz’s six illustrations of blue clothes in a broader context.

![Calm waters at ‘Wampoo’ [Whampoa] in China, included as an introduction in the 19-year-old Carl Fredrich von Schantz’s East India travel journal. He was not trained in natural history, as he was an apprentice for the Admiralty on board the East India ship. However, he made a selection of natural history drawings and other depictions in watercolour, which are still pristine. These original illustrative documentations were inserted as separate plates between the copied text pages in the handwritten Swedish journal, a copied, revised version – in his own hand – due to that the first page recorded the exact return date of the voyage ’20 June in 1749’ and this introductory image with ‘the year 1749’. One motivating factor for this effort to document in the text as well as the image may have been that on the same ship – Götha Lejon – another young officer, the 18-year-old Carl Johan Gethe (1728-1765), also kept a detailed journal including watercolours. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 7).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/1a-m-800x631.jpg) Calm waters at ‘Wampoo’ [Whampoa] in China, included as an introduction in the 19-year-old Carl Fredrich von Schantz’s East India travel journal. He was not trained in natural history, as he was an apprentice for the Admiralty on board the East India ship. However, he made a selection of natural history drawings and other depictions in watercolour, which are still pristine. These original illustrative documentations were inserted as separate plates between the copied text pages in the handwritten Swedish journal, a copied, revised version – in his own hand – due to that the first page recorded the exact return date of the voyage ’20 June in 1749’ and this introductory image with ‘the year 1749’. One motivating factor for this effort to document in the text as well as the image may have been that on the same ship – Götha Lejon – another young officer, the 18-year-old Carl Johan Gethe (1728-1765), also kept a detailed journal including watercolours. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 7).

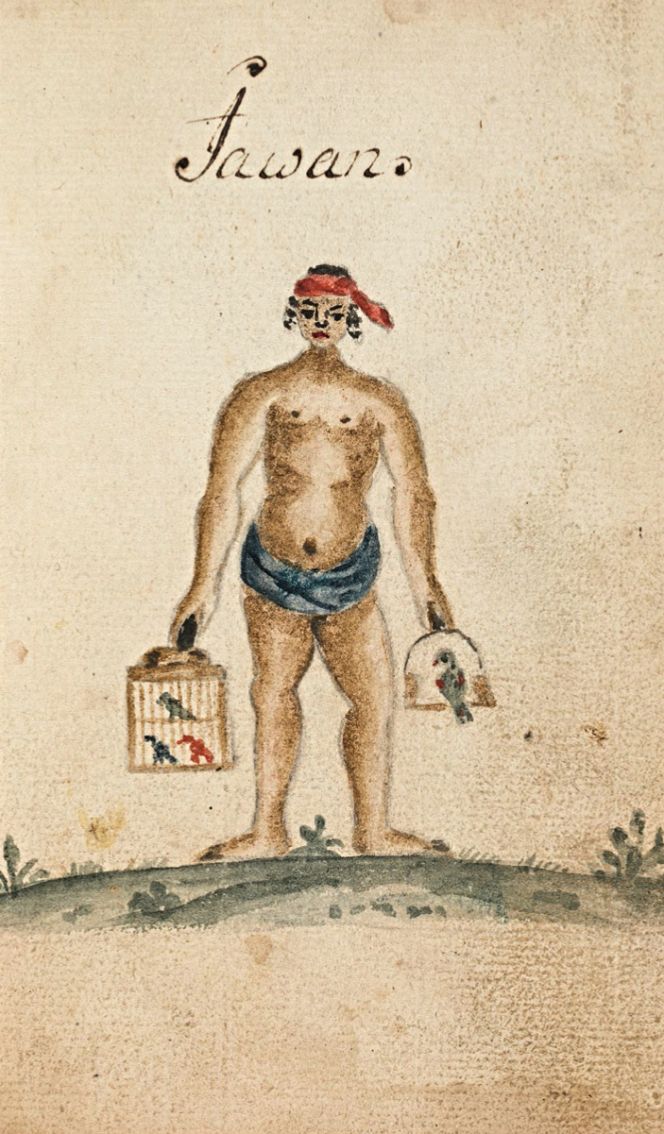

Calm waters at ‘Wampoo’ [Whampoa] in China, included as an introduction in the 19-year-old Carl Fredrich von Schantz’s East India travel journal. He was not trained in natural history, as he was an apprentice for the Admiralty on board the East India ship. However, he made a selection of natural history drawings and other depictions in watercolour, which are still pristine. These original illustrative documentations were inserted as separate plates between the copied text pages in the handwritten Swedish journal, a copied, revised version – in his own hand – due to that the first page recorded the exact return date of the voyage ’20 June in 1749’ and this introductory image with ‘the year 1749’. One motivating factor for this effort to document in the text as well as the image may have been that on the same ship – Götha Lejon – another young officer, the 18-year-old Carl Johan Gethe (1728-1765), also kept a detailed journal including watercolours. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 7). The 19-year-old Carl Fredrich von Schantz travelled on the ship ‘Götha Leijon’ in the same year as Carl Linnaeus’ apostle Christopher Tärnström (1711-1746) sailed on the ‘Calmar’ towards China. Taken from the youth’s travel notes is this Javanese wearing the typical loincloth according to the country's custom. Schantz described the local men’s loincloth briefly, without any note about the material or dyes used for the illustrated blue cloth. This was the kind of dress Tärnström observed on his visit to Java, however, whereas his notes make no mention of indigo-dyed fabrics. That the man depicted used a blue fabric was no coincidence, as the tradition of dyeing blue had by that time already long been in existence in the Javanese archipelago, just as in many other tropical and subtropical warm regions where the plant Indigofera tinctoria thrived. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 66).

The 19-year-old Carl Fredrich von Schantz travelled on the ship ‘Götha Leijon’ in the same year as Carl Linnaeus’ apostle Christopher Tärnström (1711-1746) sailed on the ‘Calmar’ towards China. Taken from the youth’s travel notes is this Javanese wearing the typical loincloth according to the country's custom. Schantz described the local men’s loincloth briefly, without any note about the material or dyes used for the illustrated blue cloth. This was the kind of dress Tärnström observed on his visit to Java, however, whereas his notes make no mention of indigo-dyed fabrics. That the man depicted used a blue fabric was no coincidence, as the tradition of dyeing blue had by that time already long been in existence in the Javanese archipelago, just as in many other tropical and subtropical warm regions where the plant Indigofera tinctoria thrived. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 66).Carl Fredrich von Schantz, among many other Swedes, became part of global culture via the East India trading company – from which his journal reveals reflections of his interest, amazement and, at times, distraction via his observations of diverse societies and everyday life in visited places. Overall, he appears to have been interested in local communities intertwined with facts about natural history and geographical matters along the sea route. In Cadix, when sailing past Teneriffe, The Line [Equator], Cape of Good Hope, Java, in particular at the main destination Canton and on the homeward leg through Bangka Strait, at anchors at Ascension Island, the English Channel and the North Sea before reaching Göteborg on 20 June in 1749 after ’32 months and 2 days.'

Schantz did not mention textile dyes – like indigo or other dye plants in his journal – so this was probably not a subject the young man had any knowledge about. His watercolours, however, clearly show which colours various groups of inhabitants in Canton preferred or were obliged to wear during the 1740s, which in combination with other contemporary written sources, gives a good understanding of the traditionally used colours on clothing. In Schantz’s written notes (pp. 97-101), on the other hand, one must be more cautious because he seems to have been uncertain about the textile materials used and the choice of colours. A few text sections will be quoted in a translation from Swedish to exemplify his lack of confidence in connection with such matters:

"Mandarins and Merchants use black silk fabric coats, and there under white plain woven linen [probably of cotton] coats, somewhat shorter than the outer garment, the trousers are of white and brown linen [cotton], wide modelled and tied at the knee, on the legs, they use boots made of damask, which to the half is white and half is blue, the white on the top and blue at the bottom, the seam is midway on the leg, the shoes [he refers to the lower part of the boots] are of black damask and soles of pigskin… which are either red, yellow, white or blue in colour if one may see if someone is very distinguished or belongs to the small Mandarines, due to which colour they use, that I know nothing about… (pp. 97-98)."

Of textile interest are several drawings depicting the inhabitants’ clothes at the destination of Canton. Carl Fredrich von Schantz’s captions included these colourful costumes of predominantly indigo blue, which read in translation: ‘Mandarin’, ‘Mandarin’s Wife ’, and ‘Ordinary Soldier’. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 103).

Of textile interest are several drawings depicting the inhabitants’ clothes at the destination of Canton. Carl Fredrich von Schantz’s captions included these colourful costumes of predominantly indigo blue, which read in translation: ‘Mandarin’, ‘Mandarin’s Wife ’, and ‘Ordinary Soldier’. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 103).The naturalist-cum-ship’s chaplain Pehr Osbeck’s (1723-1805) focus on dyes in China was indigo and a few other plants; indigo was mainly described in general terms without any specific details on the methods of dyeing. His most detailed observations on the voyage with the Swedish East India Company from 1750 to 1752 (10 & 12 Sept. 1751 in his diary) are evidence of the plant being cultivated in profusion outside Canton, where it was stressed that indigo grew best on the uppermost slopes, often happily companion-planted with cotton. It was even the case that, in the 18th century in that area, it was as important a cultivated plant as rice and cotton. Crop rotation was a method of planting often employed, indigo and rice alternating every two years, which was thought to keep the dyers sufficiently supplied with the blue dyestuff. He also established that in Canton, dyers were to be found in streets along with other artisans, such as apothecaries, bookbinders, mirror makers, shoemakers, etc. The Chinese language had two different words for indigo: Tång ann or Wå. Alum, the essential mordant, was also sold in Canton and was described as ‘fine and clear’. That product was not required for dyeing with indigo but was essential for dyeing textiles using many other colours.

Osbeck, a former student of Carl Linnaeus, interestingly visited Canton only a few years after Carl Fredrich von Schantz, whose watercolour illustrations of indigo blue clothes reveal more about the frequent use of blue dyes for men working on various local boats. Particularly evident in the three chosen images below.

Two men wearing short coats and trousers of indigo blue fabric in a ‘Mandarin Sampan’. Watercolour by Carl Fredrich von Schantz, November 1747. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 118).

Two men wearing short coats and trousers of indigo blue fabric in a ‘Mandarin Sampan’. Watercolour by Carl Fredrich von Schantz, November 1747. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 118). The men wore the same style of indigo blue clothing in this ‘Hoppos Sampan’. The ‘Hoppos’ were inspectors of maritime merchandise between Whampoa – where foreign ships unloaded their goods – and Canton, so this category of local workers had frequent direct contact with the European East India Companies. Judging by the watercolour (November 1747), the ‘Hoppos’ must have been visible at a close distance as Carl Fredrich von Schantz made such a detailed illustration of their boat, clothing, etc. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 123).

The men wore the same style of indigo blue clothing in this ‘Hoppos Sampan’. The ‘Hoppos’ were inspectors of maritime merchandise between Whampoa – where foreign ships unloaded their goods – and Canton, so this category of local workers had frequent direct contact with the European East India Companies. Judging by the watercolour (November 1747), the ‘Hoppos’ must have been visible at a close distance as Carl Fredrich von Schantz made such a detailed illustration of their boat, clothing, etc. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 123). In a final watercolour of local inhabitants in the Canton area, Carl Fredrich von Schantz also made a depiction of a ‘Long Sampan’ in February 1748 – on a boat where all rowers and drummers alike were visibly dressed in indigo blue coats and trousers with a contrasting red hat. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 129).

In a final watercolour of local inhabitants in the Canton area, Carl Fredrich von Schantz also made a depiction of a ‘Long Sampan’ in February 1748 – on a boat where all rowers and drummers alike were visibly dressed in indigo blue coats and trousers with a contrasting red hat. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… M 292, p. 129).Whilst the naturalist-cum-ship’s surgeon Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828), who travelled with the Dutch East India Company in the 1770s, made enlightening observations on indigo dyeing on Java, which was also observed via a watercolour by Carl Fredrich von Schantz (see image 2). Indigo was as valuable for the export market as was the dyestuff for the dyeing of cloth for the use of the country’s own needs. Ever since the beginning of the 17th century, when Batavia was founded by the Dutch, the dye-plant was one of the East India Company’s most important trading commodities. For domestic use, many women on the Indonesian islands learnt how to dye, and they mastered not only the art of dyeing but also how to produce resist-dyed weaves. However, dyeing with indigo was considered a most difficult art, of which only a limited number of families had the knowledge and skill, and the craft of dyeing yarn for the most complex ikat fabrics was handed down from mother to daughter. It is unclear from the journal whether Thunberg came across women who dyed using indigo, but he did study the plant in gardens around Batavia. Those plantations were run by Chinese who grew sugar cane and coffee besides indigo. It was also recorded that in addition to the small-scale Chinese plantations, the plant ‘grew wild everywhere.'

Indigo may have been the dominant dye in the area, but other plants also produced durable colours. Yet again, the Chinese were described as knowledgeable and involved in the process, using the plant Mangustinos, Garcinia mangostana, which was brought from Bantam to Batavia and used for dyeing black. From the visit in 1775, Thunberg’s travel journal recorded: ‘...and is only to be had at a certain time of the year, which is in January and the months following. The rind is of a purple colour on the outside and pale within, soft, of an astringent nature.’ A plant that could produce red dyes was Morinda citrifolia, the root of which dyed red just like the common madder. The difference is that, like indigo, the Morinda species could be dyed in lukewarm water, an unusual characteristic in natural dyeing. During his second visit to Java, Thunberg noted two more plants which were used for dyeing blue. In June 1777, after nearly six months on the island, he wrote: ‘Korang garing and Tampalulan are two plants, with which the Javanese dye blue.’ The fact that Thunberg’s most significant interest was focused on dyeing blue further demonstrates the enormous importance of the colour as much for Java and its vicinity as for the country’s export.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (Chapters of: Pehr Osbeck, Christopher Tärnström and Carl Peter Thunberg).

- Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm, Sweden (National Library of Sweden); ‘En kort beskrifning uppå en Ostindisk resa till Canton uthi China. Förrättat af Carl Fredrich von Schantz Ifrån åhr 1746 Till åhr 1749.’ (M 292). | Dagbok hållen på Resan till Ost Indien, Begynt den 18 octobr: 1746 och Slutad den 20 Juni 1749’ by Carl Johan Gethe (M 280) .

- Osbeck, Peter [Pehr], A Voyage to China and the East Indies, 2 vol., London 1771.

- Sandberg, Gösta, Indigo: en bok om blå textilier, Stockholm 1986.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

- Tärnström, Christopher, Christopher Tärnströms journal – En resa mellan Europa och Sydostasien år 1746, Mundus Linnæi Series No: I, edited by Kristina Söderpalm, London & Whitby 2005.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE