ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

INSPIRATION FROM EARLIER TRADITIONS

– in Late 19th Century Textiles

The bourgeois in Sweden favoured a rich selection of heavy fabric qualities together with dark-coloured wallpapers and furniture – for their home sphere and interior design – in the later years of the 19th century. New ideas were mixed with influences originating in traditional art-woven textiles from rural areas and nostalgic period styles both dating centuries back. This essay will continue to examine the evidence and historical circumstances connected to Malmö in the southernmost part of the country. Foremost in the context of everyday life and material culture within the home and how a number of individuals, primarily within the well-to-do, preferred and became advocates for this particular trend. They were textile artists, writers, historians, painters, exhibitors at various world exhibitions, early museum founders, etc.

Interior from a well-to-do Malmö home in the 1890s. The fashionable draperies were clearly inspired by the farming communities’ textile traditions and used motifs from earlier time periods (ca 1700-1850) in close-by rural areas. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MM FK267).

Interior from a well-to-do Malmö home in the 1890s. The fashionable draperies were clearly inspired by the farming communities’ textile traditions and used motifs from earlier time periods (ca 1700-1850) in close-by rural areas. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MM FK267).One idea was to copy patterns from century-old textiles and change the design to one’s own taste – as in the above image – another way was to cut up, re-shape and use the original woven fabrics or embroideries for other purposes in a “modern” apartment. If not adjusted for its new environment, the tapestries were kept in their original sizes and placed side by side on a wall, for example, to cover a corner of a room combined with Persian carpets, heavy draperies of dark colours decorated with tassels or fringes, “Orient” inspired fancy goods etc. Everything was mixed and admired as good taste, but a few decades later – or already by some contemporaries – the style was seen as old-fashioned and cluttered.

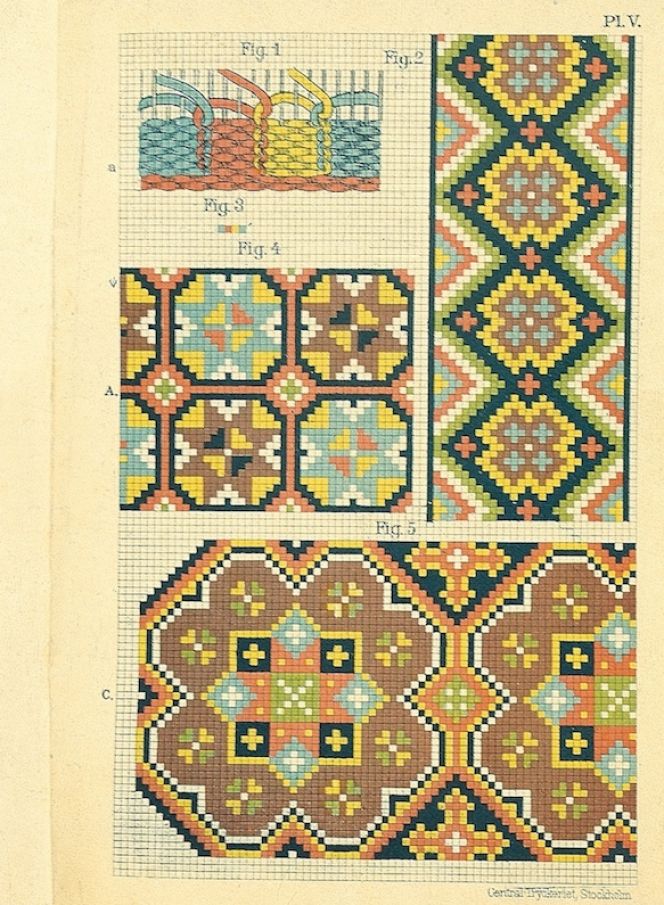

Practical weaving book by Maria Collin printed in 1890. The aim of her book was to explain the technique “rölakan” or double interlocked tapestry and give examples of the wide range of colours and ornaments from the previous long-lived traditions of such cushions, bench covers etc in southernmost Sweden. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

Practical weaving book by Maria Collin printed in 1890. The aim of her book was to explain the technique “rölakan” or double interlocked tapestry and give examples of the wide range of colours and ornaments from the previous long-lived traditions of such cushions, bench covers etc in southernmost Sweden. (Photo: The IK Foundation, London).Maria Collin (1864-1933) published three books in the 1890s on the theme of art weaving from the most southerly province of Skåne. At this time, she corresponded with the elderly artist and researcher Nils Månsson Mandelgren (1813-1899), who had been one of the earlier advocates for the preservation and historical knowledge of traditional craft, including hand-weaving and embroidery. He had made observations in the province between 1850 to 1872. Furthermore, he founded Svenska Slöjdföreningen (the Swedish Craft Organisation) in 1845 and visited craft exhibitions on the Continent, for example, the World Exposition in Vienna 1873, where he noticed Swedish textiles of techniques and designs included in Collin’s books two decades later.

“In the chest chamber” is one in a series of similar paintings by the artist Jakob Kulle from the 1870s and 1880s. The observations always included various interiors from 19th century farming communities in southernmost Sweden – with the traditional textiles and clothing as featured focal points. (Owner: Malmö Museum. Photo: The IK Foundation, London).

“In the chest chamber” is one in a series of similar paintings by the artist Jakob Kulle from the 1870s and 1880s. The observations always included various interiors from 19th century farming communities in southernmost Sweden – with the traditional textiles and clothing as featured focal points. (Owner: Malmö Museum. Photo: The IK Foundation, London).Jakob Kulle (1838-1898) was an artist who made a number of depictions of everyday life in the rural area of Skåne. However, he was not solely a painter; studies of historical textiles were another area of expertise. This knowledge was particularly useful in 1874 when he became one of the founders of Handarbetets Vänner (Friends of Handicraft) in Stockholm. Their philosophy was foremost to get inspiration from the old textile traditions and develop these patterns into new designs for up-to-date uses. Kulle had the vital role of finding suitable female weavers for the Friends of Handicraft in the capital and purchasing tapestries and embroideries in the southernmost province. A connection to Malmö was, for instance, an exhibition at an agricultural meeting in 1881; admirers as well as critics of the “new textile collection” – inspired and altered from the old tapestries, etc – were equally heard.

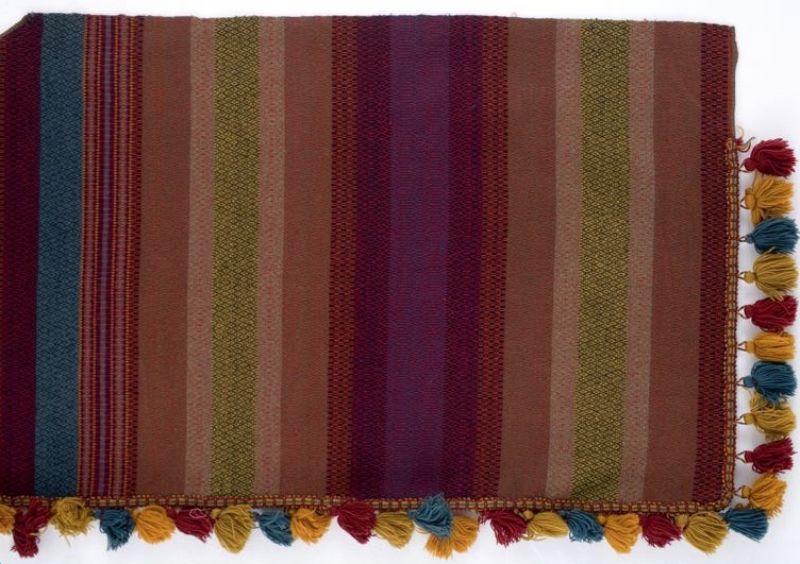

One of a pair of curtains dated 1888; hand-woven with cotton warp and woollen weft in strong synthetic colours. The designer is unknown, but the fabric in “rosepath” was strongly inspired by bench covers and cushions in technique/design/motifs from rural farming communities pre-1850s. Furthermore these decorative curtains were used in a bourgeois Malmö apartment at Östergatan in the late 19th century – as part of the interior design of a family’s dining-room, possibly purchased in a shop or ordered to fit this particular room. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MM 042280:009).

One of a pair of curtains dated 1888; hand-woven with cotton warp and woollen weft in strong synthetic colours. The designer is unknown, but the fabric in “rosepath” was strongly inspired by bench covers and cushions in technique/design/motifs from rural farming communities pre-1850s. Furthermore these decorative curtains were used in a bourgeois Malmö apartment at Östergatan in the late 19th century – as part of the interior design of a family’s dining-room, possibly purchased in a shop or ordered to fit this particular room. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MM 042280:009).![A study of photographs taken in Malmö in the 1890s, reveals that at least two shops sold yarn. This particular image was taken in 1899, the corner of Södergatan and Balzarsgatan situated in the central parts, by the local photographer Axel Sjöberg. In the “Malmö Nya Garnbod” [Malmö New Yarn shop] customers could purchase yarn for leisure activities, educational needlecraft, embellishing clothing or for details in interiors – like woollen yarn to make strong coloured tassels as on the image above. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: EH: 002116).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/5-garnaffar-800x575.jpg) A study of photographs taken in Malmö in the 1890s, reveals that at least two shops sold yarn. This particular image was taken in 1899, the corner of Södergatan and Balzarsgatan situated in the central parts, by the local photographer Axel Sjöberg. In the “Malmö Nya Garnbod” [Malmö New Yarn shop] customers could purchase yarn for leisure activities, educational needlecraft, embellishing clothing or for details in interiors – like woollen yarn to make strong coloured tassels as on the image above. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: EH: 002116).

A study of photographs taken in Malmö in the 1890s, reveals that at least two shops sold yarn. This particular image was taken in 1899, the corner of Södergatan and Balzarsgatan situated in the central parts, by the local photographer Axel Sjöberg. In the “Malmö Nya Garnbod” [Malmö New Yarn shop] customers could purchase yarn for leisure activities, educational needlecraft, embellishing clothing or for details in interiors – like woollen yarn to make strong coloured tassels as on the image above. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: EH: 002116). Notice: A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of notes, see the Swedish article by Viveka Hansen.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Fyra sekel Malmö textil – 1650 till 2000’, Elbogen pp. 23-91, 1999 (pp. 54-59).

- Malmö Museum, Sweden (Online collection, three images & information – catalogue cards).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE