ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

MANGLING AND IRONING

– Laundry Tools and Traditions in Whitby: 1700 to 1914

Linen becomes smoother if mangled, that is to say, taken when still slightly moist and rolled backwards and forwards between large wooden rollers under considerable pressure. The earliest mangles were developed in the 18th century and variously called box-mangle or table mangle. These were extremely heavy to use, but during the next century, models with various mechanisms and wheels were developed, making them more accessible to women. This essay will take a closer look at primary sources which give evidence for mangling in Whitby, together with a wide variety of preserved tools connected to ironing. Including; box irons with or without a stand, glass smoothers for linen, horseshoe stands for irons, Italian “tally” irons, cap irons, metal boxes with wick and stand for curling irons as well as goffering block and roller for shaping collars and other garments.

Goffering block and roller, inscribed on the back, ‘Hannah Barnbridge Craig 1804’. This is one of two preserved sets that could be used on collars, cuffs, nightcaps and other aspects of clothes that needed crimping and goffering. The model is made entirely of wood with a grooved wooden block, 10 x 15 cm, and a matching small grooved roller; such a model was in use as early as the 18th century. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History, SOH 370). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Goffering block and roller, inscribed on the back, ‘Hannah Barnbridge Craig 1804’. This is one of two preserved sets that could be used on collars, cuffs, nightcaps and other aspects of clothes that needed crimping and goffering. The model is made entirely of wood with a grooved wooden block, 10 x 15 cm, and a matching small grooved roller; such a model was in use as early as the 18th century. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History, SOH 370). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

The earliest written sources from Whitby that mention smoothing irons are 18th century probate inventories. It may be assumed that these implements were to be found in most homes, even if they are not always explicitly described but were probably included under ‘other small implements’ or ‘household goods’ since the recorded irons were of no great value. Other mentions are more specific. John Elrington’s inventory of July 1709 contains ‘A smoothing cloth’ valued at 10 pence which must have been either an underlay used while ironing or a piece of cloth placed between the garment and the iron to prevent the iron from damaging the garment. Elrington also owned ‘A smoothing box and heaters’ worth 1 shilling 7 pence, that is to say, a box iron with at least two extra metal sections, which would have been alternately heated on the fire and fitted to the box part of the iron. A ‘smoothing box’ was also to be found among the possessions in February 1725 of George Cockerill, a master mariner from Bagdale. In March 1743/44, Charles Lightfoot, Bailiff of Whitby Strand, owned ‘2 flat smoothing irons, 2s.’: that is to say, irons with a flat underside that could be heated on the fire to the desired temperature. The same inventory also contains an ‘old broken iron, 1s.’ and ‘2 clothes presses, 3s.’; it is not clear what kind of iron is meant by these ‘presses’. In 1752 a ‘Box and heaters’ worth 3 shillings is found with Miles Sweeting and in 1760 a ‘smooth box’ worth 7 shillings with Jane Small. A final example is dated January 1771 John Gibson owned ‘1 smoothing box and heaters’ also valued at 7 shillings. Thus the commonest type of iron in the 18th century was the box iron with heaters that could be inserted alternately to keep the iron as hot as possible. This was also the cleanest method of ironing since the iron itself never needed to be near the fire, which avoided the risk of scorching the garment being ironed.

Victorian box iron of an ordinary model, whilst two of the box irons from this period in the researched collection is in miniature format and were thus specially intended for areas otherwise difficult to reach on collars and smocks, etc. The collection also contains two ‘stands’, one of which is horseshoe shaped; the iron could be rested on a stand of this kind either during use or when not needed in the household. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History, SOH333.) Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Victorian box iron of an ordinary model, whilst two of the box irons from this period in the researched collection is in miniature format and were thus specially intended for areas otherwise difficult to reach on collars and smocks, etc. The collection also contains two ‘stands’, one of which is horseshoe shaped; the iron could be rested on a stand of this kind either during use or when not needed in the household. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History, SOH333.) Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Whilst the ‘glass linen smoothers’ listed in probate inventories are very heavy mushroom-shaped objects in a dark glass 15-20 cm high that could be used for smoothing out the cloth. According to the donor – R. Lionel Foster, Esq. of Egton Manor, 1931 – these linen smoothers date back to the 17th century. The Whitby Museum collection also contains ‘goffering tongs’, scissors-like long tongs with flat blades that were in common use in the 1850s. These would be heated over the fire, then used to grip the cloth and goffer it to the desired form. One such pair of iron tongs (SOH 344) also has yarn added at the end to protect the user against burning herself. Both the early forms of box iron and the 19th century models functioned just as described above for the probate inventories, with heaters that were placed inside the box.

There are also four ‘Italian “tally” irons’ in the collection. This was a type of smoothing iron very popular in the Victorian age, with its curved foot and holder into which interchangeable ‘heaters’ could be inserted. It was used for the finer details of lace, small pleats, goffering frills, etc. Attached to one of these (SOH 336) is an interesting label: ‘Purch. R. Gray & Son’. This a reference to one of Whitby’s larger draper shops, which according to advertisements in the Whitby Gazette, was opened in 1874 and still in existence after 1914. This particular Italian smoothing iron is decorated with a heavy brass foot that extends into the ironing section, while the upper part is strong porcelain lined inside with iron. The handle is wood to protect the user from burning her fingers.

The other three irons of this type are made entirely of iron, two of them being small, while the third is 30-35 cm high and has an attractive leaf-shaped foot (SOH 338). Another piece of special equipment used for ironing was the ‘cap ironer’ or ‘lumphead’. Two varieties of this have been preserved, one entirely of iron while the other, the larger one, is 25-30 cm high and has an iron extremity in the form of three lion’s feet joined to a brass rod with a round top also made of brass, on which caps could conveniently be formed and rounded to the desired shape (SOH 347). Interestingly, a wooden hand mangle and roller were also acquired together with another wooden hand mangle from Whitby (1896.72.1) through Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt-Rivers (1827-1900), though it is not known who the local collector was. The items were incorporated in Pitt-Rivers’ collection in Oxford in October 1896 and originally described as ‘Two old Yorkshire wooden hand-mangles (oak), one with a roller, Whitby 15/-’.

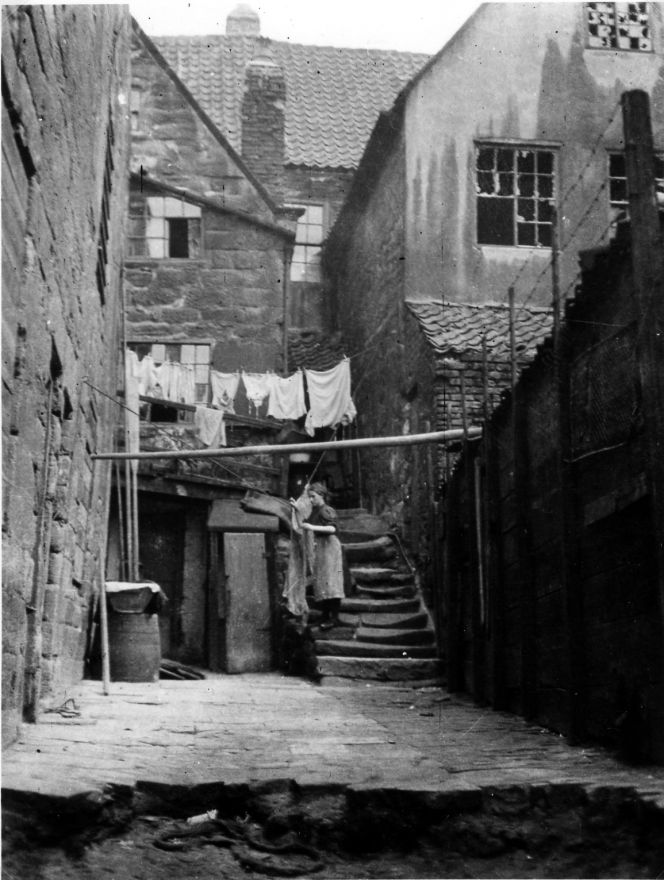

It is not possible to be sure whether this woman in Argument’s Yard in Whitby was washing for her family or was a professional laundress, but all the censuses list many women in Church Street and its yards who worked in the laundry business. Clothes and linen were often put out to dry in backyards. Research of the Poor Law valuation and continuous census returns during the 19th century also reveals that mangle houses were located along Church Street or the nearby yards. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Photograph Book Four, 4/15).

It is not possible to be sure whether this woman in Argument’s Yard in Whitby was washing for her family or was a professional laundress, but all the censuses list many women in Church Street and its yards who worked in the laundry business. Clothes and linen were often put out to dry in backyards. Research of the Poor Law valuation and continuous census returns during the 19th century also reveals that mangle houses were located along Church Street or the nearby yards. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Photograph Book Four, 4/15).It may be supposed that the two ‘Mangle-houses’ in the 1837 Poor Law valuation of Whitby contained large mangles of the improved type. The ‘Angel Inn’, owned by Esther Yeoman in Baxtergate, was valued as high as £123 and among the many facilities she was able to offer was a ‘Mangle-house’. In contrast, Ann Allinson’s ‘Mangle-house and chamber’ was valued at only £1 10s. Some of the census returns also recorded houses containing a mangle and women who mangled. In 1851 such mangles were found on Church Street; in 1861, in both Church Street and Baxtergate; and finally in 1871, in Church Street and Wade’s Yard. Earlier smaller and handier upright mangles began to appear in the later decades of the 19th century and continued to be popular because they were easier to use, easier to accommodate and cheaper.

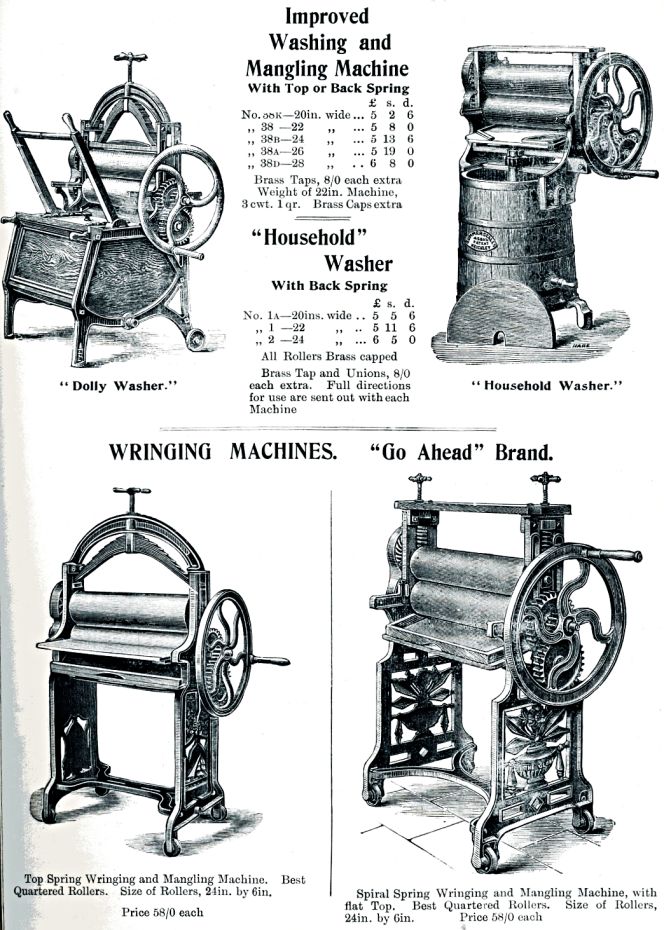

Mangles of this type can be found in the 1902 Richd. Johnson, Clapham & Morris catalogue, by which time most models combined more than one function, either as a ‘washing and mangling machine’ or a ‘wringing and mangling machine’, showing the most effective and essential aids of the day to laundry. (From: J C M Catalogue 1902 p. 395).

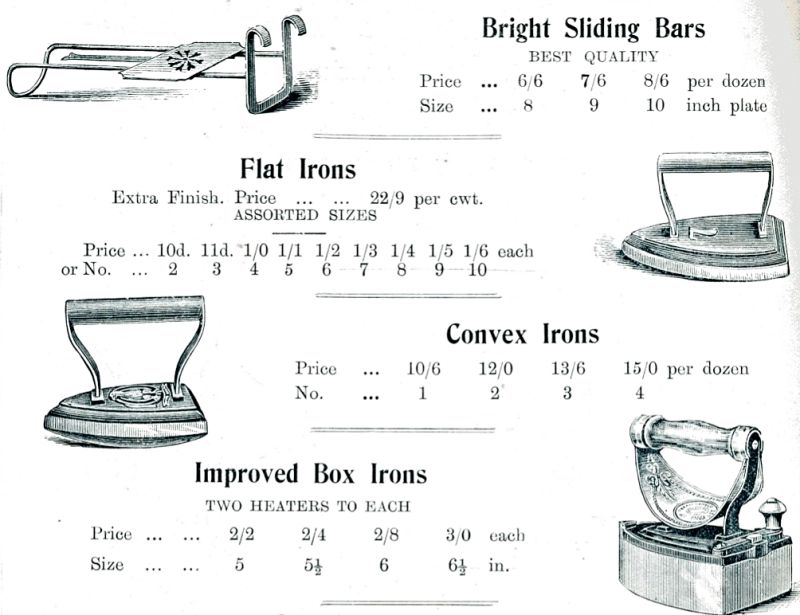

Mangles of this type can be found in the 1902 Richd. Johnson, Clapham & Morris catalogue, by which time most models combined more than one function, either as a ‘washing and mangling machine’ or a ‘wringing and mangling machine’, showing the most effective and essential aids of the day to laundry. (From: J C M Catalogue 1902 p. 395).  A second example from the same catalogue visualised and informed about three different types of irons. The models of flat, convex and an improved box iron with a protective handle for the heat, which the earlier Victorian model illustrated in this essay lacked. (From: J C M Catalogue 1902 p. 384).

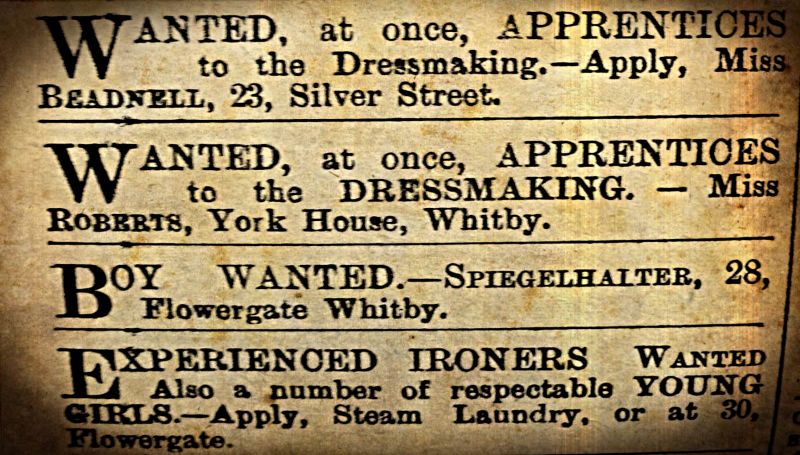

A second example from the same catalogue visualised and informed about three different types of irons. The models of flat, convex and an improved box iron with a protective handle for the heat, which the earlier Victorian model illustrated in this essay lacked. (From: J C M Catalogue 1902 p. 384). Looking for ‘Ironers’ was relatively uncommon in announcements in the local newspaper Whitby Gazette, but occurred several times in the year 1900. For instance, evident in this advert from the Steam Laundry wanted ‘Experienced Ironers’ and ‘a number of respectable Young Girls’ to work in their laundry business. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Gazette 1900, April-June). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Looking for ‘Ironers’ was relatively uncommon in announcements in the local newspaper Whitby Gazette, but occurred several times in the year 1900. For instance, evident in this advert from the Steam Laundry wanted ‘Experienced Ironers’ and ‘a number of respectable Young Girls’ to work in their laundry business. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Gazette 1900, April-June). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.A novelty at the turn of the century was mangling with steam, as advertised in Cook’s 1901 Directory by ‘Stakesby Steam Laundry, Stakesby Road; receiving office, 30 Flowergate – Thornton & Co., proprietors. However, the old box mangle was better than the smaller mangles if one wanted really smooth linen. Certainly, the steam laundry technique also ensured really smooth work, but some fabrics – particularly linen – would eventually suffer damage from the high temperatures used in these machines. The only garments and home textiles suitable for mangling were fabrics without folds or uneven areas, like sheets, tablecloths, napkins and handkerchiefs. All mangles ultimately derive from the very oldest form of mangling with board and roller, that is to say by winding the material to be mangled onto a roller and then rolling it backwards and forwards on the table by pressing the mangling-board on top at right angles to the roller. These boards, often given as engagement presents, were also frequently beautifully carved and painted. But no surviving examples of such decorated tools have been found in the Whitby Museum Collection of this early method of mangling.

Sources:

- Cook, W. J. & Co., Whitby and District Directory, Whitby 1901.

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914: A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015 (pp. 305-308).

- Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, England (1896.72.1. Mangle and roller from Whitby).

- Richd. Johnson, Clapham & Morris Limited, General Catalogue, Manufacturers, Merchants, Hardware factors and Complete house Furnishers, Manchester 1902.

- The National Archives at Kew, England (Poor Law Valuation, Whitby 1837.

- Whitby, North Yorkshire Country Library, England (Census: Whitby and Ruswarp; 1841-1901 microfilm).

- Whitby Museum, England. Whitby Lit. & Phil. | Library & Archive & Social History Collection (Research of Whitby Gazette 1855-1914, irons, smoothers and other equipment for ironing).

- Vickers, Noreen, A Yorkshire town of the 18th century, Whitby 1986.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE