ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

PINS AND NEEDLES

– Textile Observations by 18th Century Naturalists on Long-distance Journeys

Carl Linnaeus’ seventeen Apostles, who undertook natural history journeys to more than 50 countries between 1746 and 1799, have been part of my research for more than two decades. For this essay, some of these naturalists’ observations will provide enlightening details about needles and pins used in connection with textiles and trade, together with similar reflections by Linnaeus himself during his provincial tours in Sweden from the 1730s to the 1740s. These useful textile tools were kept on pincushions, in small boxes or needle cases for safekeeping. Needles and pins were also part of the handcrafted trade and still at this time regarded as valuable commodities, made of either brass, steel or iron. A wide range of primary sources has assisted this study, including contemporary 18th century travel journals, listed expenses, artworks and preserved physical objects, which reveal global encounters from the perspective of the small needles and pins.

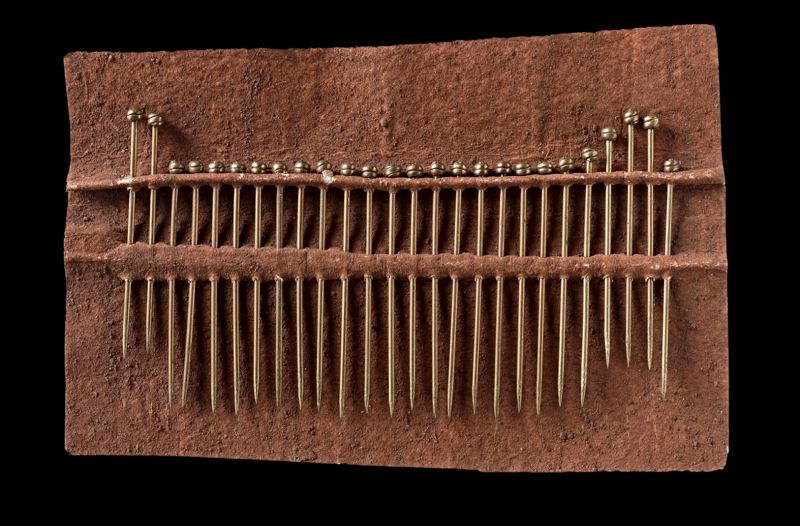

This is one of several preserved sample pages of brass pins, once part of Anders Berch’s collection. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0017648B:493. DigitaltMuseum).

This is one of several preserved sample pages of brass pins, once part of Anders Berch’s collection. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0017648B:493. DigitaltMuseum).Anders Berch (1711-1774) was appointed to a professorial chair in Uppsala in 1741, as was Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) during the same year. Berch’s tools, as well as textile samples of multiple materials, colours and weaving techniques, were intended for use as teaching material for his students and together with many other objects formed a significant part of his collection. The amassing of East Indian fabrics took place mainly during the 1750s and 1760s, which most probably was the same for these pins, illustrated above, due to a note from the original cataloguing in 1877. In translation from Swedish, it recorded: ‘B.493 Pins, 26 pieces, brass with wire heads, length 3,5 cm, Chinese marks’. The manufacturing of pins may not have been made in the trading city of Canton (Guangzhou) itself, however, judging by diary notes by the contemporary naturalist and ship’s chaplain Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) who travelled with the Swedish East India Company around 1750. From his stay in the Canton area, he mentioned needles as well as pins in September 1751: ’The Chinese tailors’ scissors are small, but exactly like ours in every other respect. Their needles have round eyes, 100 of them cost a mes. Pins are not made here. Instead of the smoothing iron, they have a little pan, without feet of brass or copper, into which they put some burning charcoal, and rub the seams…’

Although these hand-forged pins, made in the 18th century, had remained much the same in appearance for a long time. Such tools became necessary when tailors began to cut cloth during the second half of the 14th century and needed pins to hold the various pieces of material in place during sewing. The more slender needles available for sewing in the Middle Ages were also significant in the development of the art of needlework and the making of clothes. From a view of natural history journeys during the 18th century, these small objects were mainly mentioned in various documents, in contexts other than textiles, by Carl Linnaeus and his Apostles. First and foremost for the usefulness for naturalists’ collection work and in particular pins for insects. While other practical needs for pins recorded in travel journals were: hair could be curled assisted by pins in Amsterdam, by pricking patterns on the skin in North America, for acupuncture in Japan, as well as that pins and needles were part of a multifaceted trade in Russia. Pins equally appear to have been popular in a gift exchange and barter between the Europeans and indigenous groups of people in the Pacific. Urban and rural as well as local and global cultures were intertwined in these easily portable objects.

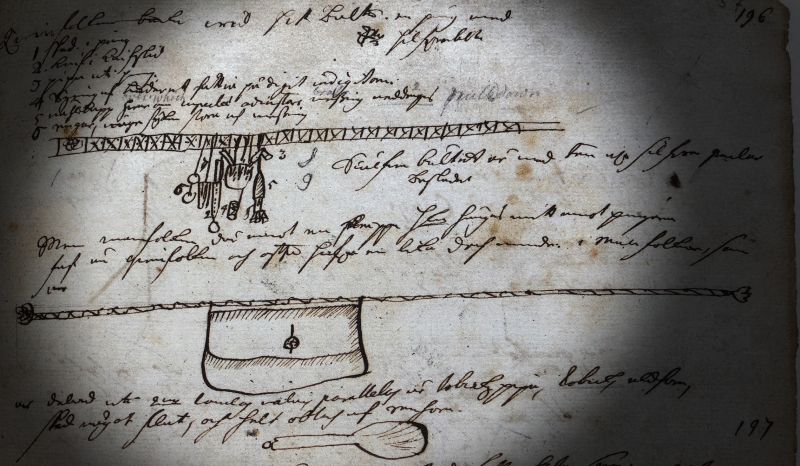

‘Norvegia’ is what Linnaeus called the Sami region belonging to Norway in his journal from the Lapland Journey in 1732. On 16 July, he described and illustrated costume details in his diary, which included a needle case. It was the women’s silver belts, along with the necessary possessions attached to them, which were examined according to his drawing. Two of the items have a direct link with the production of clothes, namely an embroidery hoop of leather and a needle case. The sewing hoop was likely a handy tool for stretching fabrics to achieve perfect seams, while the sewing needles were valuable possessions and were kept in a closed needle case. (Collection: The Linnean Society of London. | Close-up detail of note no. 196 in the original diary). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, London.

‘Norvegia’ is what Linnaeus called the Sami region belonging to Norway in his journal from the Lapland Journey in 1732. On 16 July, he described and illustrated costume details in his diary, which included a needle case. It was the women’s silver belts, along with the necessary possessions attached to them, which were examined according to his drawing. Two of the items have a direct link with the production of clothes, namely an embroidery hoop of leather and a needle case. The sewing hoop was likely a handy tool for stretching fabrics to achieve perfect seams, while the sewing needles were valuable possessions and were kept in a closed needle case. (Collection: The Linnean Society of London. | Close-up detail of note no. 196 in the original diary). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation, London.Two years later, during his journey to the province of Dalarna, Linnaeus equally reflected on traditional clothing and needle cases. In particular, in the parish of Mora, on 8 July 1734, Linnaeus notices in his diary that the women around the waist wore a leather belt and tied to this belt, they attached a needle-case, keys and a knife in its sheath. Whilst during the Västergötland Journey, at the manufacturers at Alingsås on 7 July 1746, in the otherwise exhaustive descriptions of this textile enterprise in his journal, without any further details listed, ‘The needle making workshop’. This particular workshop had been a part of the Alingsås manufactures – founded in 1723 by Jonas Alström (1685-1761) – since at least 1726 when the following workshops were located at this place: needle making, hat manufacturing, passementerie, upholstery, the printing of calico as well as weaving of broadcloth, stockings, ribbons and various other woollen cloths.

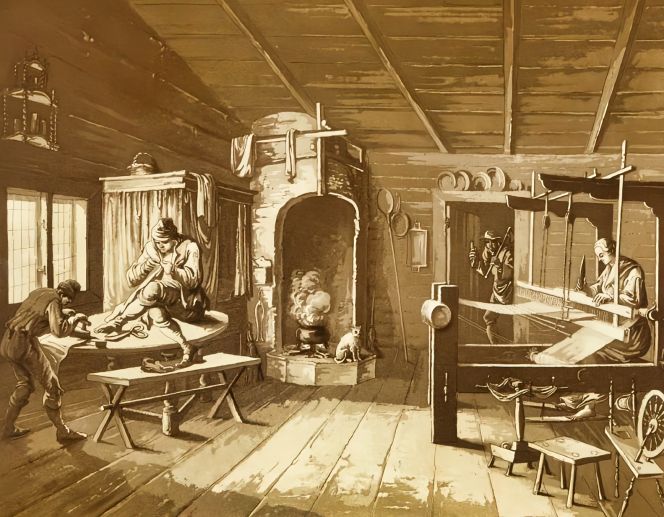

Aquatint by Johan Fredrik Martin (1755-1816) depicted a farmer’s cottage, probably during the period 1784-87, at a time when the artist travelled around the Swedish countryside. (Courtesy: Stockholmskällan. No: SSM 100304. Creative Commons).

Aquatint by Johan Fredrik Martin (1755-1816) depicted a farmer’s cottage, probably during the period 1784-87, at a time when the artist travelled around the Swedish countryside. (Courtesy: Stockholmskällan. No: SSM 100304. Creative Commons). In this artwork, the journeyman tailor and his apprentice reveal details of interest, with the tailor sitting cross-legged on the table, stitching a garment with thread and needle. Simultaneously, as his apprentice was ironing a cloth. Overall, people in the Swedish countryside during the 18th century tended to hand their home-woven or purchased fabrics to the tailors, or as in this case, the tailor stayed in their home for the time needed to have their clothes made up according to whatever style was current. Making skirts with bodices, breeches, and outer garments was a skill hard to master, requiring a special craftsman. Whilst embroideries and various linen garments, on the other hand, were, as a rule, done by the women themselves in rural areas.

A few of Carl Linnaeus’ long-distance travelling naturalists have given further information about needles and pins from a much wider geographical area – London, Quebec, Montreal, Egypt, Russia and West Africa – in their preserved writings. These reflections from a textile perspective could have had aims like admiration or disapproval of traditions learned via the indigenous population in the various places, as they saw it at the time, notes of pure interest or necessary accounts that listed one’s expenses during the journey. In a chronological sequence, Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) was on his way to the North American colonies, a journey which lasted from October 1747 to the return home to Sweden in the summer of 1751. He sailed from Göteborg on a ship via Norway to England, accompanied by his assistant, Lars Jungström, where they stayed for approximately six months. Most of the time spent in London, surrounded by the metropolis, Kalm’s detailed travel accounts listed needles and pins among many commodities.

The various stages of needle making, illustrated on an 18th century etching, are comparable to Pehr Kalm’s travel accounts in London. On 23 June 1748, he purchased: 'Stitching and sewing needles, 2d.’, ‘Silk, blue, green, yellow, black, 1Sh. 6d.’ and ‘Thread of several colours, at 2d per ounce. 1Sh. 2d.’ The following day the list also included ‘Darning needles, 1d.’ Even if these items were chiefly intended for use in the natural history collections and the stitching together of sheets of paper, needles and pins were also useful during a several-year-long journey for darning socks and patching worn-out clothes. (Courtesy: Wellcome Collection 33002i).

The various stages of needle making, illustrated on an 18th century etching, are comparable to Pehr Kalm’s travel accounts in London. On 23 June 1748, he purchased: 'Stitching and sewing needles, 2d.’, ‘Silk, blue, green, yellow, black, 1Sh. 6d.’ and ‘Thread of several colours, at 2d per ounce. 1Sh. 2d.’ The following day the list also included ‘Darning needles, 1d.’ Even if these items were chiefly intended for use in the natural history collections and the stitching together of sheets of paper, needles and pins were also useful during a several-year-long journey for darning socks and patching worn-out clothes. (Courtesy: Wellcome Collection 33002i).Two further notes on the subject of pins and needles were included in Kalm’s travel journal. From Quebec on 8 September 1749, he made a description of the Inuits’ traditions and their interactions with the Europeans. ‘Esquimaux…the needles with which they sew their clothes are likewise made of iron or bone. All their iron they get by some means or other from the Europeans.’ Kalm himself never travelled far enough north to have the chance to meet them personally, but through a number of individuals’ experiences, he managed to create a picture for himself of how they were dressed, etc. His extensive journal also gave examples of how the French in Canada carried out trade with the Indigenous peoples. Steel or iron needles were part of the commerce, too. From Montreal on 22 September 1749, his journal reflected on: ‘Hatchets, knives, scissors, needles, and steel to strike fire with these instruments are now common among the Indians. They all take these instruments from the Europeans, and reckon the hatchets and knives much better than those which they formerly made of stones and bones.’ Ill health, in general, seems to have been the most common ailment onboard a Swedish East India Company ship in the years 1753-56, judging by Linnaeus’ apostle Carl Fredrik Adler’s (1720-1761) medical journal, but as a ship’s physician on a merchant ship nonetheless, he had to know about surgical procedures, primarily amputations.

In the coming decade in a totally different part of the world, the naturalist Peter Forsskål (1732-1763) was one of six participants who in the autumn of 1760 were assembled in København to determine their plans for Den Arabiske Rejse (The Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia), which they began on 7 January 1761. An observation linked to needles has been traced in his diary from March-April 1762, when Forsskål’s diary listed goods transported via the Mecca and Cairo caravan. In the direction from Cairo, the caravan, among a multitude of goods carried ‘Sewing-needles’ and ‘Large sewing-needles’ as well as ‘Silk thread and fabric from Syria’. Syria had a central position in the far-flung Ottoman Empire and was consequently a centre for trading, with Damascus as its focal point. It was also recorded that caravans went directly from Syria to Mecca, bypassing Cairo. Taking part in those journeys was, in other words, made by competing merchants who traded in the same type of goods but via different caravan routes. ‘The Syrian Mecca caravan’ took a route heading practically straight south, carrying larger quantities of silk, potentially making the price more favourable for the Mecca customer.

The naturalist Johan Peter Falck (1732-1774) led one of the Imperial Academy of Sciences’ natural history expeditions from September 1768 up to his death in 1774; posthumously, his comprehensive travel journal was published. A journal that had been kept over a five-year journey that was to stretch across widespread areas of land in present-day Russia and Kazakhstan, significantly greater distances than any of the other apostles covered overland. Falck’s way of amassing facts and, with meticulous precision, giving account for the most varied disciplines bore great similarities with Linnaeus’ methods of working. Traded goods were quite often in focus from different regions; in some cases, needle-making was part of this information. Firstly, from the River Oka region, where Falck visited a textile establishment in Oka and noted in his journal that: ‘There are two linen factories here, each with about 60 looms, producing Raventuch, light sailcloth, hemp canvas and striped linen, mostly for export, and also some table linen. The factories buy the flax and hemp yarn from the farmers for 1-5 roubles a pood. Apart from these, the town also has a needle factory.’ As he continued his journey into the River Ural region, he made in-depth recordings of the trade in his journal. Interestingly, the notes included needles, pins and fine textiles among other desired goods by the Kighiz and Bukharan peoples:

- The Kirghiz… ‘They take in exchange coarse and fine cloth, silk and half-silk Chinese and Astrakhan material, velvet, dyes, dyed linen, ribbons and cords, thread, yuft, safyan, lace, beads, beaver and otter pelts, saddles and bridles, stirrups, waistbands, rings, earrings, buttons, buckles, snakeheads (cyprea), thimbles, needles, combs, scissors, mirrors, padlocks, chains, axes, trivets, iron griddles, copper, tin and wooden utensils, long Russian knives, lighters, large bells and miniature bells, tobacco, tobacco pipes and boxes, pepper, sugar, groats, millet and flour.’

- The Bukharans… ‘They take away the fine cloth, heavy silk cloth, sole-leather, indigo, cochineal and other dyestuffs, gold thread, metal implements, brass and iron stirrups, mirrors, needles and pins, padlocks, scissors, beads and all kinds of haberdashery, sugar-candy, ginger, copper sulphate, ordinary glue and fish glue, cast-iron cooking-pots and otter pelts.’

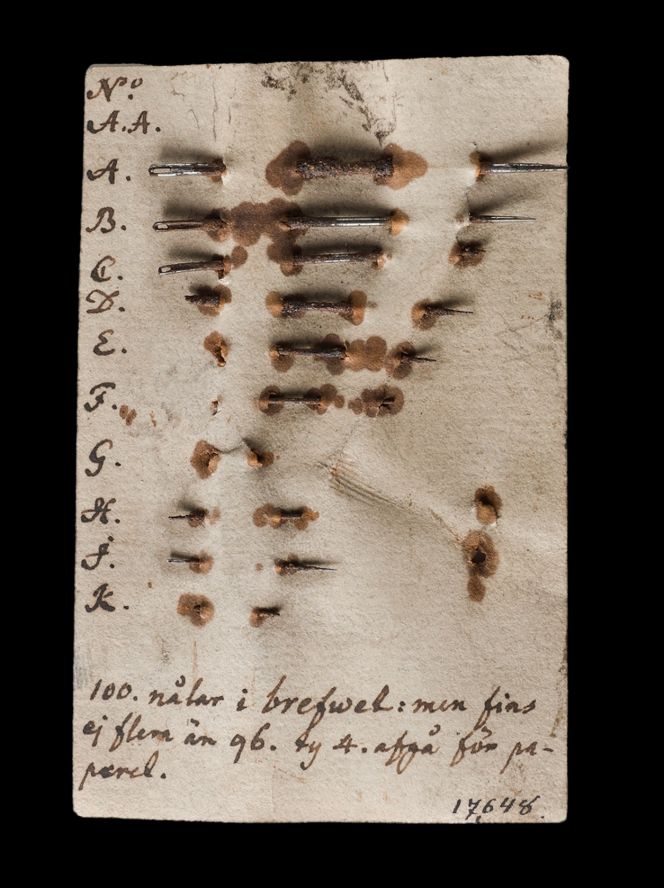

18th century needles. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0017648B:501. & 502 notes only. DigitaltMuseum).

18th century needles. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0017648B:501. & 502 notes only. DigitaltMuseum).In conclusion, these small objects, used in varied settings around the world, shown above with a second example from the Anders Berch Collection, demonstrate a selection of steel needles in various sizes, dating from circa the 1740s to the 1760s. The disadvantage of steel (before the invention of stainless steel) and iron, compared to brass, is clearly visible via the substantial corrosion on these needles. The text reads in translation: ‘100 needles in this letter: but there are no more than 96, due to that 4 is used for the paper [paper parcel]’. Additionally, the collection includes a small sample page of sewing needles of steel, in the eight stages of the manufacturing process, with a description, which makes it likely that these sewing needles, as well as the illustrated examples, were domestically made.

Sources:

- Hallberg, Paul & Olsson, S. Bertil, ed., En ostindiefarande fältskärs berättelse – Carl Fredrik Adlers journal från skeppet Prins Carl 1753-56, Göteborg 2013.

- Hansen, Lars, ed. The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Vol. Two: Johan Peter Falck’s journal, Vol. Three: Pehr Kalm’s journal, Vol. Four: Peter Forsskål’s journal & Vol. Seven: Pehr Osbeck’s journal).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017.

- Kalm, Pehr, Pehr Kalms Amerikanska reseräkning, published by Svenska Litteratursällskapet in Finland, Helsingfors 1956.

- Kjellberg, Sven T., Ull och Ylle, Malmö 1943.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa på riksens högloflige… förrättad åhr 1746, Stockholm 1747.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Linnés Dalaresa – Iter Dalecarlicum, Stockholm 1953.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Iter Lapponicum – Lappländska resan 1732. (Ed. A. Hellbom, S. Fries & R. Jacobsson). vol. I., Umeå 2003.

- The Linnean Society of London, United Kingdom (Visit in the year 2000. Research of Carl Linnaeus’ original diary ‘Iter Lapponicum…1732’. The Linnean Collections).

- The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. (Anders Berch Collection: needles and pins. Information on online catalogue cards. DigitaltMuseum).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE