ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

THE STORY No. 6 | FIELDWORK – THE LINNAEAN WAY

Pockets, Shoes, Boots, Hats & Wigs on Naturalist Journeys

This Essay is part of the long-term research and publicise project

THE STORY | FIELDWORK THE LINNAEAN WAY

Describing pockets on clothes was relatively rare in various writings by travelling naturalists during the 18th century, but it was even so a theme that reoccurred in various daily life happenings. Pockets were overall useful for a multitude of practical reasons during field observations. A selection of contemporary artworks, trade cards, and preserved clothing, including visible proofs of pockets, presents further links to these young men’s notations in Europe, the North American colonies, French Polynesia, Asia, and Africa. This essay will also examine several such recordings closely, drawing on preserved journals and correspondence by Carl Linnaeus, his so-called Apostles, and other individuals in their network. Just as having proper shoes or boots for one’s feet, hats as cover for rain and sun, as well as the use of wigs during a natural history journey.

![This illustration, taken from Peter Forsskål’s (1732-1763) autograph book, dated Göttingen 1755, represents the former Carl Linnaeus student Forsskål and his fellow student Frederik Seidelin (1733-1775), dressed entirely according to the European fashion of the time. Their coats had visible large pockets, which were helpful during botanical excursions for the two students of the University of Göttingen. Such a book was at times part of one’s personal belongings and could replace a letter of Introduction as the student’s teachers and others had already written some sentences in the book before the journey, studies abroad or a Grand Tour, etc. Forsskål also kept a second autograph book, used during the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia, with names included from his time in Copenhagen [København] and later on. After his death, the book was retrieved by the sole survivor, Christian Niebuhr, and brought back to Denmark in 1767. (Courtesy: Det Kongelige Bibliotek [The Royal Library] København, Denmark).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/1-a-forsskal-800x496.jpg) This illustration, taken from Peter Forsskål’s (1732-1763) autograph book, dated Göttingen 1755, represents the former Carl Linnaeus student Forsskål and his fellow student Frederik Seidelin (1733-1775), dressed entirely according to the European fashion of the time. Their coats had visible large pockets, which were helpful during botanical excursions for the two students of the University of Göttingen. Such a book was at times part of one’s personal belongings and could replace a letter of Introduction as the student’s teachers and others had already written some sentences in the book before the journey, studies abroad or a Grand Tour, etc. Forsskål also kept a second autograph book, used during the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia, with names included from his time in Copenhagen [København] and later on. After his death, the book was retrieved by the sole survivor, Christian Niebuhr, and brought back to Denmark in 1767. (Courtesy: Det Kongelige Bibliotek [The Royal Library] København, Denmark).

This illustration, taken from Peter Forsskål’s (1732-1763) autograph book, dated Göttingen 1755, represents the former Carl Linnaeus student Forsskål and his fellow student Frederik Seidelin (1733-1775), dressed entirely according to the European fashion of the time. Their coats had visible large pockets, which were helpful during botanical excursions for the two students of the University of Göttingen. Such a book was at times part of one’s personal belongings and could replace a letter of Introduction as the student’s teachers and others had already written some sentences in the book before the journey, studies abroad or a Grand Tour, etc. Forsskål also kept a second autograph book, used during the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia, with names included from his time in Copenhagen [København] and later on. After his death, the book was retrieved by the sole survivor, Christian Niebuhr, and brought back to Denmark in 1767. (Courtesy: Det Kongelige Bibliotek [The Royal Library] København, Denmark).The practical importance of sizeable pockets on garments can also be seen in a letter from the naturalist Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) to Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), sent a few months after his return back to Göteborg in the autumn of 1752, when he had been employed as a ship’s chaplain on a Swedish East India Company, he informed about the difficulties experienced – not to risk his clothes, his money or even his life – when collecting plants in the Canton area, and added that ‘I was glad to note what was necessary with my pencil and the notebook kept in my pocket’. Whilst the botanist Johann Gerhard König (1728-1785) included a kind or maybe ingratiating comment in a long letter to Linnaeus, sent from Tranquebar in India 1769, about how he ‘had shown the bishop of the island Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae, which he brought with him in his pocket’. Furthermore, in an earlier letter dated 26 September 1767, sent from København, he had hopes of obtaining Systema Naturae before leaving Denmark and noted that his departure might not be until the middle of November. Due to his comment in 1769, it appears that König managed to obtain a copy of the book in time for his travels.

After Anton Rolandsson Martin’s journey (1729-1785) to Spitsbergen in 1758, on the way home through southernmost Sweden, it may be glimpsed from the later-written autobiography that he must have had large pockets. He described how cumbersome it was to wash the one and only shirt he possessed; when it had become too dirty to be worn, the shirt was dipped in water, beaten against a stone, and then stuffed into his pocket to dry, thereby forcing him to go without a shirt for a whole week while it slowly dried.

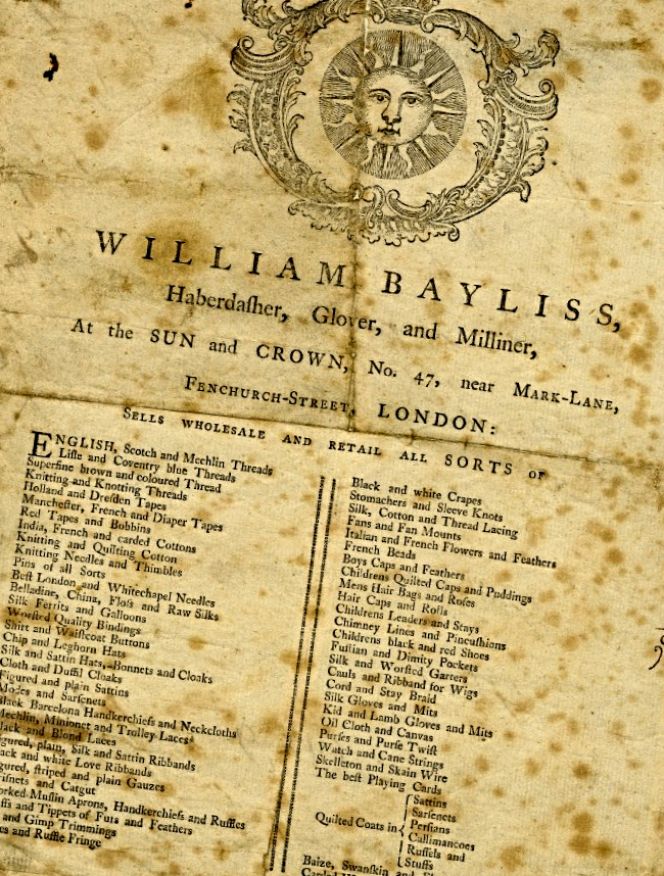

This detailed trade card from a London ‘Haberdasher, Glover, and Milliner’ dated 1769 at the back, reveals rare information about the business that sold ‘Fustian and Dimity Pockets’. Qualities were woven of a hard-wearing twill-fustian, mostly came in one single colour and were distinguished by checks or stripes, both suitable for pockets. One may assume that these were standard fabrics for pockets, as such items are included on several trade cards in this collection. (Courtesy: Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 70.7, Collection online).

This detailed trade card from a London ‘Haberdasher, Glover, and Milliner’ dated 1769 at the back, reveals rare information about the business that sold ‘Fustian and Dimity Pockets’. Qualities were woven of a hard-wearing twill-fustian, mostly came in one single colour and were distinguished by checks or stripes, both suitable for pockets. One may assume that these were standard fabrics for pockets, as such items are included on several trade cards in this collection. (Courtesy: Trustees of the British Museum, Trade cards, Heal 70.7, Collection online).One of Linnaeus’ other former students, Christopher Tärnström (1711-1746), made notes in his journals of the thorough search of pockets during their stopovers in Cadix as ship’s chaplains on Swedish East India Company ships. Tärnström gave the following account on 10th March 1746: ‘…Otherwise, they would have searched one’s pockets for snuff and tobacco at the gate, something which is very strictly controlled in Spain, as it is the merchandise of the King. And if anyone brings in a pipe of tobacco or the smallest amount of snuff in his box he will be arrested and carried on the galleys as a lifetime prisoner, which did indeed happen to one or other of our sailors on previous voyages who had to be bought back.’ Whilst the earlier mentioned Pehr Osbeck made a similar observation – ‘Those that go out are visited with a strictness beyond description…’ – of the search of pockets on 13th January 1750, and overall, the authoritarian rules seem to have been a worry for the travellers. It may also be noted that even being chaplains on a ship, they had to be dressed in ordinary European men’s clothing in Cadix, as it was not allowed to wear Lutheran clergyman’s dress in Catholic Spain.

The somewhat later portrait of the Spanish architect Ventura Rodríguez (1717-1785), dated 1784, provides accurate details of large pockets on the coat and smaller ones on the waistcoat, still very similar in style to those of the 1750s, which can be compared to the landscape portrait above and observations in contemporary journals. Oil on canvas by Francisco de Goya (1746-1828). (Courtesy: National Museum, Sweden. NM 4574. Wikimedia Commons).

The somewhat later portrait of the Spanish architect Ventura Rodríguez (1717-1785), dated 1784, provides accurate details of large pockets on the coat and smaller ones on the waistcoat, still very similar in style to those of the 1750s, which can be compared to the landscape portrait above and observations in contemporary journals. Oil on canvas by Francisco de Goya (1746-1828). (Courtesy: National Museum, Sweden. NM 4574. Wikimedia Commons). This well-preserved man’s coat and waistcoat, circa 1760-1780, must have been similar in style to garments used by the travelling naturalists. Both clothing items were stitched of fine red broadcloth with additional practical pockets. When a three-piece suit like this was used, the breeches probably also had side pockets, so the wearer of such a suit had at least six pockets. (Collection: Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom. The exhibition: ‘Europe 1600–1815’). Photo: Viveka Hansen, October 2017.

This well-preserved man’s coat and waistcoat, circa 1760-1780, must have been similar in style to garments used by the travelling naturalists. Both clothing items were stitched of fine red broadcloth with additional practical pockets. When a three-piece suit like this was used, the breeches probably also had side pockets, so the wearer of such a suit had at least six pockets. (Collection: Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom. The exhibition: ‘Europe 1600–1815’). Photo: Viveka Hansen, October 2017.In his advice to visitors in hot climates, side pockets for breeches/trousers and their practical uses were mentioned by the naturalist Henry Smeathman (1742-1786), whom the Linnaeus apostle Andreas Berlin (1746-1773) worked for during a journey to West Africa in 1773. Smeathman wrote: ‘Upon a visit, people now and then wear a coat or jacket which are of no use except to carry one’s handkerchief, snuff box and odd things; but two large side pockets in one’s trousers and two before will, in general, suffice to carry such things as are necessary. Side pockets are convenient for carrying pocket pistols, which I think no European should be without on the coast of Africa.’

The practical aspects of pockets in warm climates during field observations were also briefly mentioned by Daniel Rolander (1723-1793) in Suriname on 5 July 1756: ‘…nor had they yet made the identification that I was such a man as was under the necessity of putting away and carrying in the pockets of my clothes every specimen of Nature that I had chosen to examine or dry.’

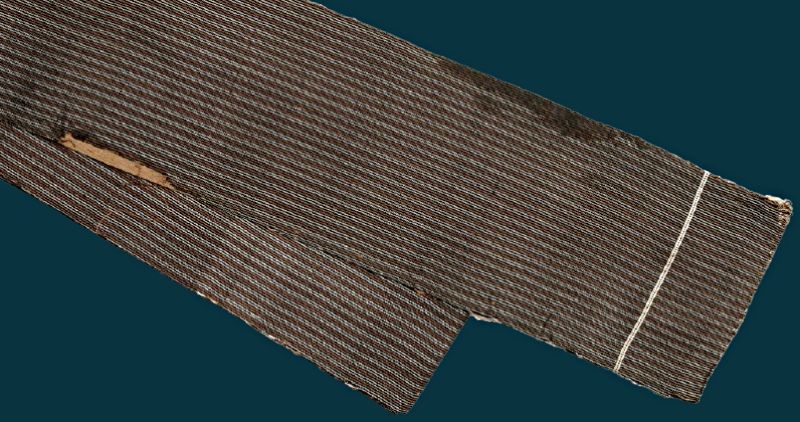

Carl Peter Thunberg, who visited Japan in 1775 and 1776, described the rigorous search of his own pockets, etc. every time when disembarking and reembarking the ship in Nagasaki's harbour and how the Japanese kept their smaller items safe. On 4 September 1775: ‘Both these searches are very strict; so that not only travellers’ pockets are turned inside out, and the officers’ hands passed over their clothes…’ Whilst this depicted example is a brown striped sash of silk, a so-called obi, ten cm wide, to be used with a man’s dress, which was brought back by Thunberg from his voyage. The sash forms an essential part of the traditional Japanese costume, serving both to hold one or more nightgowns together and to attach personal items, as Japanese garments typically did not have pockets. (Courtesy: Museum of Ethnography, Stockholm. No: 1874.01.0092. Online collection).

Carl Peter Thunberg, who visited Japan in 1775 and 1776, described the rigorous search of his own pockets, etc. every time when disembarking and reembarking the ship in Nagasaki's harbour and how the Japanese kept their smaller items safe. On 4 September 1775: ‘Both these searches are very strict; so that not only travellers’ pockets are turned inside out, and the officers’ hands passed over their clothes…’ Whilst this depicted example is a brown striped sash of silk, a so-called obi, ten cm wide, to be used with a man’s dress, which was brought back by Thunberg from his voyage. The sash forms an essential part of the traditional Japanese costume, serving both to hold one or more nightgowns together and to attach personal items, as Japanese garments typically did not have pockets. (Courtesy: Museum of Ethnography, Stockholm. No: 1874.01.0092. Online collection). During Anders Sparrman’s (1748-1820) two periods in the Cape province from 1772 to 1776, he on several occasions mentioned his useful pockets. For instance: ‘a luncheon of bread and butter doubled together, and stuffed into my coat-pocket’, ‘filled our pockets in all haste with loose gunpowder’ or ‘I caught one of them [a lizard] at the Warm Bath, and, wrapping it up in paper, kept it in my pocket’.

A negative experience from their European viewpoint, connected to pockets, was mentioned during James Cook’s (1728-1779) second voyage, where Anders Sparrman took part as an assisting botanist, as well as on the first voyage, where the Linnaeus apostle Daniel Solander (1733-1782) had the same position. According to the journals of Sparrman and James Cook, as well as the journal of the artist Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771) from Cook’s first voyage, they often had to take great care not to be pickpocketed in French Polynesia. Sparrman noted that he had handkerchiefs in his pockets, but if he used handkerchiefs made from their cloth of mulberry tree bark instead, he minimised the problem (22 Aug. 1773). Two weeks later, he mentioned pockets in such terms as ‘defend my pockets against his thieving compatriots’ or ‘…I did not carry my knife separately in a side pocket of my trousers’. On the first voyage, Cook also noted (14 April 1769): ‘Notwithstanding the care we took Dr Solander and Dr Monkhouse had each of them their pockets picked the one of his spyglass and the other of his snuff-box…’ and about two months later Parkinson (3 June 1769) wrote: ‘Mr [Joseph] Banks lost his white jacket and waistcoat, with silver frogs; in the pockets of which were a pair of pistols, and other things…’. However, on most occasions, they seemed to have had the stolen items returned or bargained back at a later date.

Whilst proper shoes or boots for one’s feet were enormously crucial for one's health, sore and aching feet affected one’s entire well-being and, by extension, the level of collecting work. Natural history travellers probably had at least two pairs of shoes, one to wear and one tucked away among their other personal belongings. Men’s shoes at that time were of a fairly plain design, featuring black leather with a low heel and a buckle made of silver or another metal. All being observations that stretched across broad geographical areas, the Arctic, Egypt, Canton (Guangzhou), Sierra Leone, southernmost Africa, Kashmir mountains, Libya, Sweden and Portugal – assisted and illustrated by contemporary artworks and a preserved pair of shoes.

This 1790s gouache on paper by Pehr Nordquist (1771-1805) provides a comparable idea of male everyday clothing during the late 18th century, including the powdering of a wig and wearing leather boots, both of which are also mentioned by some of the travelling naturalists in their journals. Furthermore, two of the portrayed men were dressed in warm, long coats and seemed to be on their way outdoors. Even if the artist Nordquist was not part of the Linnaean network and was born somewhat later than the youngest in the chosen group of natural historians, et al., their destinies have similarities. He travelled abroad in 1801 to France and Italy, and sadly died at quite an early age in Naples in 1805, just like several of the so-called Linnaeus Apostles, due to illness in a foreign country. (Courtesy: National Museum, Sweden, NMB 1408. Wikimedia Commons).

This 1790s gouache on paper by Pehr Nordquist (1771-1805) provides a comparable idea of male everyday clothing during the late 18th century, including the powdering of a wig and wearing leather boots, both of which are also mentioned by some of the travelling naturalists in their journals. Furthermore, two of the portrayed men were dressed in warm, long coats and seemed to be on their way outdoors. Even if the artist Nordquist was not part of the Linnaean network and was born somewhat later than the youngest in the chosen group of natural historians, et al., their destinies have similarities. He travelled abroad in 1801 to France and Italy, and sadly died at quite an early age in Naples in 1805, just like several of the so-called Linnaeus Apostles, due to illness in a foreign country. (Courtesy: National Museum, Sweden, NMB 1408. Wikimedia Commons).The naturalists Daniel Solander and Joseph Banks (1743-1820), for instance, are wearing black leather shoes with silver buckles in a group portrait by the painter William Parry dating from the 1770s, as is Peter Forsskål in his picture from the mid-1750s and similarly so in many other contemporary portraits of well-to-do individuals at the time. Boots, on the other hand, did not appear in similar paintings until the late 18th century, as illustrated above; it was only then that this sturdy and functional type of footwear became an essential part of fashion. Earlier, boots were mainly associated with the military or when riding, even if they were also used by natural historians et al. in cold weather, on travels or as a social status footwear.

From the many narratives linked to the Linnaean network, Anton Rolandsson Martin briefly mentioned that he was wearing boots without stockings in his autobiography in connection to the cold and stormy voyage to Spitsbergen in 1758. As opposed to Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752), when he visited the Egyptian pyramids from 17-26 July in 1750 where he encountered problems with the use of boots in the heat: ‘I had already got to the middle of the Pyramid, and between each step found something worth notice; when the stones, heated by the sun, began to burn through my boots’. Adam Afzelius (1750-1837) also discusses the importance of shoes for maintaining health during his time in Sierra Leone in the 1790s, when he was bitten by ants and sandflies swarming around him. He therefore kept his shoes on at night for protection, as he could not find his socks. In comparison, Pehr Osbeck needed new shoes during his stay in the Canton area in 1751, as he noted that the shoemakers there could make both shoes and slippers in a European style. The quality was, however, regarded as poor as they used cotton thread for sewing, which meant that the heels and soles came off as soon as the shoes got wet.

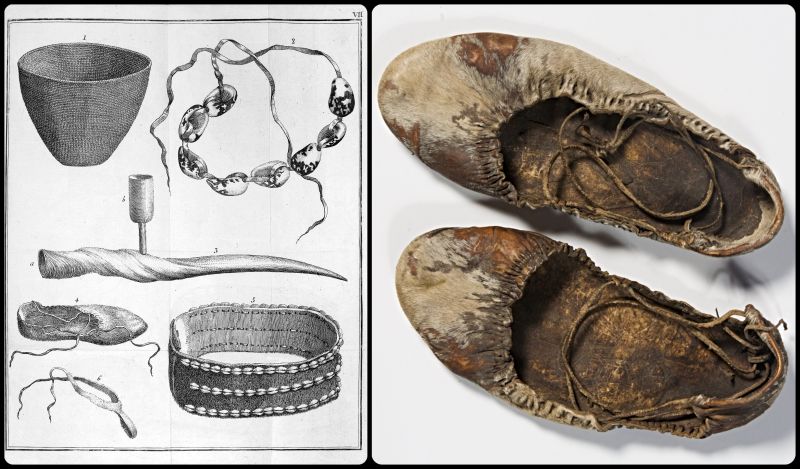

Two primary sources originate from the naturalist Anders Sparrman’s lengthy stay in the Cape region during the 1770s. ’Hottentot shoes’ with straps, are part of the many objects he brought back from the voyage to his home country. This may well be the same pair of shoes that Sparrman described in his journal, ‘...while my feet were set off with Hottentot shoes, made to draw up with strings, of the same kind with those represented in Plate I, Fig. 4’ from the English edition printed in 1786. (Courtesy: Etnografiska museet, Stockholm, Sweden, Sparrman Collection. No. 1799.02.0069 Photo: The IK Foundation, London, United Kingdom). & (Illustration from: Sparrman, Anders, A Voyage to…1786 (Plate I, vol. 1).

Two primary sources originate from the naturalist Anders Sparrman’s lengthy stay in the Cape region during the 1770s. ’Hottentot shoes’ with straps, are part of the many objects he brought back from the voyage to his home country. This may well be the same pair of shoes that Sparrman described in his journal, ‘...while my feet were set off with Hottentot shoes, made to draw up with strings, of the same kind with those represented in Plate I, Fig. 4’ from the English edition printed in 1786. (Courtesy: Etnografiska museet, Stockholm, Sweden, Sparrman Collection. No. 1799.02.0069 Photo: The IK Foundation, London, United Kingdom). & (Illustration from: Sparrman, Anders, A Voyage to…1786 (Plate I, vol. 1).Other thoughts from the same area were made by the contemporary Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1728), who in the month of August 1772, made preparations in the Cape for a longer expedition into the countryside, including the issue of footwear: ‘Shoes for the space of four months were no inconsiderable article in this account, as the leather prepared in the Indies, is by no means strong, besides, that it is quite cut to pieces, or soon worn out, by the sharp stones that occur everywhere in the mountains.’ Similar problems arose during his time in Japan regarding the ongoing wear and tear; on 18 April 1776, he noticed in the journal: ‘There is nothing which travellers wear out so fast as shoes. They are made of rice straw, and plaited, and by no means strong. The value of them too is trifling, insomuch, that they are bought for a few copper coins (Seni). There is nothing, therefore, more commonly exposed to sale in all the towns and villages, even in the smallest through which the traveller generally passes. The shoes, or rather the straw slippers which are in the most general use…’. Two other individuals in the extended Linnaean network who included notes in their travel journals about troubles linked to footwear were Michel Adanson (1727-1806) during his African journey and George Forster (died 1792) during his journey through the Kashmir mountains. Adanson’s ongoing problem was the excessive heat of the sands, in May 1749 he noted: ‘Notwithstanding the care I had taken my shoes got wet, butter not long a drying…My shoes grew tough like a horn the cracked, and fell away to powder…’ Whilst Forster tried to wear the traditional local sandals in 1783, but found such footwear uncomfortable: ‘The Kashmiris, who are the ordinary travellers of this road, use sandals made of straw rope, as an approved defence of their feet, and to save their shoes. On leaving Sumboo, I had been advised to adopt this practice, but, my feet not being proof against the rough collisions of the straw, I soon became lame and threw off my sandals…’

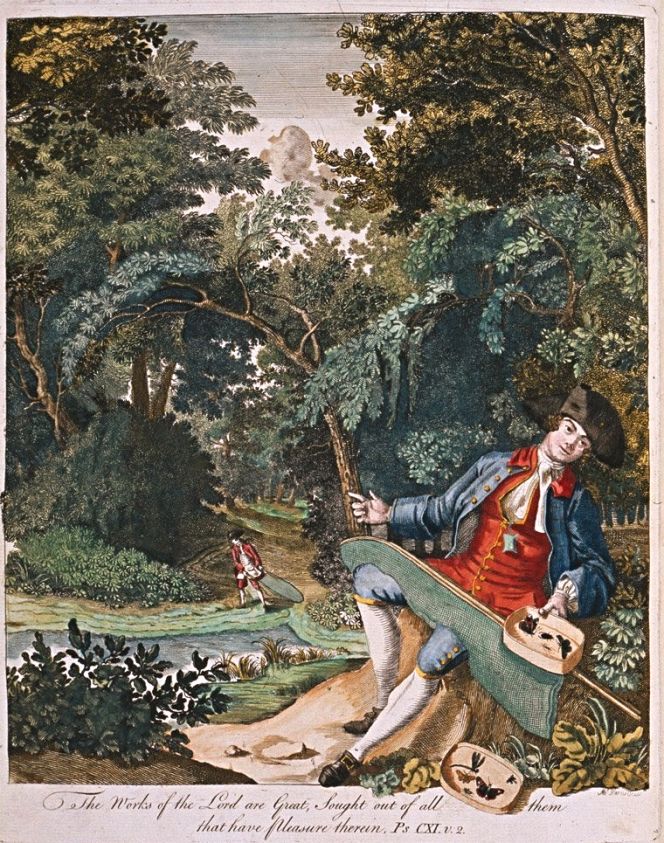

Illustration of the entomologist Moses Harris (1730-1787), probably depicted in an English landscape. This detailed frontispiece is a particularly enlightening comparison to the written words of the travelling naturalists, not only due to the mode of collecting insects in suitable wooden boxes assisted by a large-sized net, but also because Harris wore black leather shoes with buckles and a wig and a wide-brimmed hat. (From: Harris, Moses…The Aurelian frontispiece 1766).

Illustration of the entomologist Moses Harris (1730-1787), probably depicted in an English landscape. This detailed frontispiece is a particularly enlightening comparison to the written words of the travelling naturalists, not only due to the mode of collecting insects in suitable wooden boxes assisted by a large-sized net, but also because Harris wore black leather shoes with buckles and a wig and a wide-brimmed hat. (From: Harris, Moses…The Aurelian frontispiece 1766).If all sorts of footwear had advantages and disadvantages during natural history travels in various climates, the same may be said about wigs and hats. As noted in travel journals and other documents, several of these naturalists evidently wore wigs on their journeys. In the 1750s and the following decades, a man’s wig was relatively small with locks on the sides, the hair brushed up over the forehead, gathered into a plait at the back and powdered white, powder which must have been kept among their personal belongings. During the late 18th century, wigs began to fall out of fashion. Göran Rothman (1739-1778), for instance, was one of the travellers who wore a wig during his visit to Tripoli. Still, during the summer, it became far too warm to wear as he writes on 6th August in 1774: ‘I gave up using the wig, as in this climate it became much too hot for me and I started to use my own hair.’ For Pehr Löfling it was an opposite experience as he started to wear a wig during his journey, which he mentioned in a letter to his parents on 17th September 1751: ‘At Porto and St. Yves I had great difficulty keeping my hair tidy but here in Lisbon it is totally impossible which is why I am obliged to wear a wig, which you may think is hotter, but the fashion here of going around with a bare head makes it most convenient, and for me the easiest, and scarcely one in a hundred in the whole of Portugal go with their own hair.’

In cold weather, the wig could be useful together with other warming headwear, which Anton Rolandsson Martin mentioned on the voyage towards Spitsbergen on 28 April 1758: ‘The cold began to penetrate more and more through our clothes so that we had to take out our furs and periwigs. Those who did not have the means to acquire a real periwig had sewn together something from an old fur coat to set upon their heads.’ The later traveller Anders Sparrman does not appear to have worn a wig, as he described being dressed in a hat and a plait, with his hair braided, in the 1770s. The fact that there were hats in chests and trunks is possible, as this form of headwear could be used to protect against the sun and rain and ease the cold. Sparrman even used his hat to collect insects as a temporary ‘stretcher’.

Sources:

- Adanson, Michel, A Voyage to Senegal, the Isle of Goree and…, London 1759. [Quote: pp. 46-47].

- Cook, James, A Voyage towards the South Pole and Round the World, performed in His Majesty’s Ships the Resolution and Adventure. In the years 1772, 1773, 1774 and 1775, two volumes, London 1779.

- Forster, George, A Journey from Bengal to England: Through the Northern Part of ..., Volume 1–2, London 1798. [Quote: Vol. Two p. 3]

- Hansen, Lars, ed. The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012. [Information about pockets: Vol. One, Quote: p. 244/Smeathman. | Vol: Two. Rolandsson Martin | Vol. Three: Löfling & Rolander’s journal. | Vol. Four. Rothman | Vol: Five: Sparrman’s journal. | Vol. Seven: Osbeck’s & Tärnström’s journals].

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017.

- Harris, Moses, The Aurelian or Natural History of English Insects, London 1766 (2nd ed. 1775).

- Hasselquist, Fredrik, Voyages and Travels in the Levant. In the years 1749, 50, 51, 52, London 1766.

- Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien, Centrum för vetenskapshistoria, ms Bergius, Stockholm, Sweden (Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences); Anton Rolandsson Martin ‘Självbiografiska anteckningar’, manuscript.

- Parkinson, Sydney, A Journal of a voyage to the south seas in his Majesty’s ship The Endeavour, London 1773 (and enlarged edition 1784).

- Rydén, Stig, Pehr Löfling. En linnelärjunge i Spanien och Venezuela. 1751-1756, Stockholm 1965. [Quote from a letter dated 17 September 1751].

- The Linnaean Correspondence. Information & quote in translation from Swedish and German: Letter L1488: Osbeck to Linnaeus [14]25 October 1752 | Letters L3948 & L4181: König to Linnaeus 26 September 1767 and 26 February 1769. (Alvin. Online source).

- Sparrman, Anders, A Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope towards the Antarctic Polar circle round the world…1772-1776, 2 vol., London 1786.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

- Uggla, A.H.J., ‘Petrus Forsskåls stamböcker’, Svenska Linnésällskapets årsskrift 1940, pp. 86-96.

- Victoria and Albert Museum, London (visit in 2017, The exhibition: ‘Europe 1600–1815’).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE