ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

THE SURAT TRADE IN COTTON TEXTILES

– A Swedish East India Company ship: 1750-1752

This essay is the first in a two-part case study, which aims to give an in-depth analyse of trading in textiles via the Swedish East India Company ship Götha Leijon – which sailed from Göteborg in 1750 towards Surat and Canton. The ship reached its home harbour more than two years later – fully loaded with tea, porcelain, cotton textiles, silks and other desired goods. Particularly for this voyage is the number of preserved primary sources; including the ship’s chaplain and naturalist Olof Torén’s diary, in the form of letters to Carl Linnaeus, a reference book regarding various ongoing financial matters kept onboard along the route, a journal by the ship’s assistant Christoffer Henrik Braad and detailed sales catalogues of all goods and buyers. Additionally, to be compared with samples of Indian pieces of cotton brought back to Sweden via the Company ships around the same period.

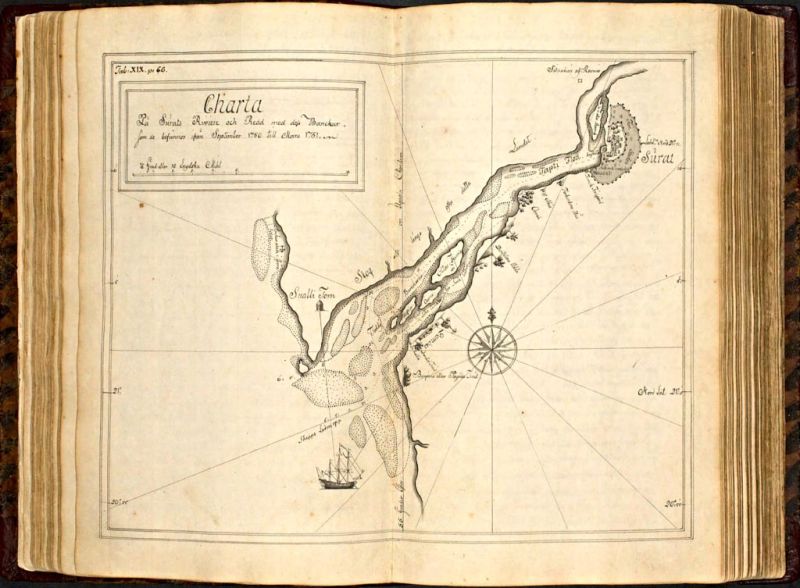

Map of Surat, which Christoffer Henrik Braad (1728-1781) included in his journal of the East India voyage, with a caption which informed that the stopover at this place lasted from ‘September in 1750 to March in 1751’. The busy trading city had a sheltered location along the Tapti River, widening to an estuary and flowing out into the Arabian Sea, from where the East India ship ‘Götha Leijon’ sailed upstream to the seaport. He initially noted: ’We arrived on the Road in Surat on 16 September in the year 1750, and before us, seven other ships had arrived, that is to say: two of the Dutch Company, two Privateers, 2 English and one Moorish, which was fully loaded and ready to sail for Bengal, which it did the same evening’. The city and other towns along the west coast of India were described and illustrated in great detail over several hundred pages, including the complex trading of cotton cloths. (Courtesy: Göteborg University Library…H 22: 3 D, p. 104 & quote p. 92).

Map of Surat, which Christoffer Henrik Braad (1728-1781) included in his journal of the East India voyage, with a caption which informed that the stopover at this place lasted from ‘September in 1750 to March in 1751’. The busy trading city had a sheltered location along the Tapti River, widening to an estuary and flowing out into the Arabian Sea, from where the East India ship ‘Götha Leijon’ sailed upstream to the seaport. He initially noted: ’We arrived on the Road in Surat on 16 September in the year 1750, and before us, seven other ships had arrived, that is to say: two of the Dutch Company, two Privateers, 2 English and one Moorish, which was fully loaded and ready to sail for Bengal, which it did the same evening’. The city and other towns along the west coast of India were described and illustrated in great detail over several hundred pages, including the complex trading of cotton cloths. (Courtesy: Göteborg University Library…H 22: 3 D, p. 104 & quote p. 92).Olof Torén (1718-1753) went on a long journey after his studies, and for a newly qualified priest, one possible option was to earn one’s living as a ship’s chaplain on the Swedish East India Company’s ships. These were extremely sought-after positions, so a recommendation and a testimonial from Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) were frequently decisive for the travel prospects. Torén was awarded the post and sailed on the ship Hoppet from Göteborg in January 1748 and the ship returned successfully via St Helena to Göteborg with its valuable cargo in July 1749. This essay, however, will focus on the ship Torén sailed with on his second voyage as a ship’s chaplain, in February 1750 he signed on the ship Götha Leijon for another voyage to Canton (today Guangzhou), that time with a stopover in Surat. Due to bad weather that winter the ship did not set sail until 1 April. During the voyage, he busied himself with collecting botanical rarities and sending plants and seeds to Linnaeus and seems on the whole to have had more contact with his master during that voyage.

On 26 July 1752, the ship was back in Göteborg. It would appear that from the outset Torén was in poor health after his second long voyage, thought to have been suffering from tuberculosis of the lungs. The year that remained of his life is likely to have been marked by that disease but the seven letters he wrote at the time have become valuable documentation of his East India voyage. Those letters were published posthumously in the form of a travel journal, first in Swedish in 1757 and later also in German, English and French. Textile material of various qualities was part of his observations from Surat. For instance, he noted that ‘their wool is more coarse and stiff than the goat’s hair...’ which was based on the fact that sheep were not bred for the properties of the wool, as warming woollen textiles were not needed in a permanent hot climate such as that of Surat. There it was cotton and silk fabrics that were used for clothes, bedclothes and curtains for wagons as protection against the sun, and privacy from the public gaze and flies. Those fabrics were among the most important trading commodities in that wealthy port. Given its good situation between the Arab countries and China, the town was, according to the traveller, an ideal trading place for all manner of precious goods despite problems with pirates and heavy monsoon rains. Of textiles, it was principally ‘Persian and Chinese silks and white striped checkered cotton’ which changed owners in the hectic port of Surat.

Several other preserved documents reveal details about the trade of textiles during this particular voyage. Foremost, one of the twenty-one sales catalogues – which date from the years 1733-1759 – from the auctions which took place weeks or a couple of months after the ships had returned to the home harbour. After the voyage to Surat and Canton, Götha Leijon return to Göteborg on 26 June in 1752 – and the auction happened on ’17 August & following days in 1752’ (together with the goods carried by the sister ship Prins Carl (which had solely visited Canton during the same period and goods linked to this ship is not included in the list below). The East India ship Götha Leijon demonstrated similar sales patterns compared to the previous twenty years of the Company’s history. With merchants, supercargoes and other traders who mainly purchased pieces of cotton and silks – as well as all other commodities. Among the names of the buyers of ‘silk goods’, ‘cotton goods’ and ‘silk goods for re-exportation'; are Colin Campbell, G. Arfwidsson, Nicholas Sahlgren, R. Parkinson, Benj. Bagge, Bagge & Comp., Koschell & Conradi, W. Chalmers and J.H. Kolthoff were listed. The Company itself also took back a smaller number of lots at this auction, in such cases prices were not indicated, so buyers were presumably not found for these particular lots.

The Anders Berch Collection, which forms a unique accumulation of 18th century fabric samples has interesting comparisons with the auction catalogue dating 1752. This collection of almost 1.700 textile samples– including East Indian fabrics of various kinds – has been scientifically examined in connection with the cataloguing and publication of the material at the Nordic Museum in Stockholm. As the Uppsala professor Anders Berch’s (1711-1774) aim with the large collection was educational, it is regarded as most probable that these samples were manufactured from 1736 up to his death in 1774. This particular preserved gingham cotton sample is of comparable quality, design and origin as: ‘Lot 1556. 1 piece of red striped gingham from Suratte, 11 aln long and 1 1/12 wide’ listed in the auction catalogue from the East India ship ‘Götha Leijon’. See the full list of sold pieces of cotton below. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum.… NM.0017648B:64A. DigitaltMuseum).

The Anders Berch Collection, which forms a unique accumulation of 18th century fabric samples has interesting comparisons with the auction catalogue dating 1752. This collection of almost 1.700 textile samples– including East Indian fabrics of various kinds – has been scientifically examined in connection with the cataloguing and publication of the material at the Nordic Museum in Stockholm. As the Uppsala professor Anders Berch’s (1711-1774) aim with the large collection was educational, it is regarded as most probable that these samples were manufactured from 1736 up to his death in 1774. This particular preserved gingham cotton sample is of comparable quality, design and origin as: ‘Lot 1556. 1 piece of red striped gingham from Suratte, 11 aln long and 1 1/12 wide’ listed in the auction catalogue from the East India ship ‘Götha Leijon’. See the full list of sold pieces of cotton below. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum.… NM.0017648B:64A. DigitaltMuseum). The listed cotton goods have been transcribed and translated into English to give an idea of the multitude of details involved – however, the noted prices and individual buyers for each and every lot are outside the scope of this essay. Even if not always mentioned, all kinds of cotton were probably ordered and purchased during the ship’s stopover in Surat, and during the short stay in Mangalore along the west coast of India.

[right-hand p. 45. aln ≈ 60 cm] ‘Cotton Goods’

- Lot 1544-1550. 350 pieces of yellow cotton tabbies

- Lot 1551. 19 pieces of ditto, whereof 5 are damaged

- Lot 1552. 1 piece of ‘Brim’ or blue and white cotton tabby from Suratte 21 1/2 aln long 1 7/12 wide

- Lot 1553. 1 piece of ‘Nockania’ or ditto cotton tabby from Suratte, 22 1/2 aln long 1 7/16 wide

- Lot 1554. 1 piece of ‘Thiul’ or ditto cotton tabby from ditto, 20 aln long 1 1/4 wide

- Lot 1555. 1 piece of ‘Chii Alledia’ 1st quality from ditto, 27 aln long 1 1/2 wide

- Lot 1556. 1 piece of red striped gingham from ditto, 11 aln long 1 1/12 wide

- Lot 1557. 2 pieces of ‘Chits’ [chintz – painted or printed calicoes] from ditto, 13 aln long 1 1/2 & 1 1/4 wide

- Lot 1558. 1 piece of Palampore from ditto, 4 aln long 3 aln wide

- Lot 1559. 2 pieces of Dimity from ditto, No: 1 & 2 10 1/4 aln long and 1 1/2 & 7/8 aln wide

- Lot 1560. 2 half pieces of ‘Duti’ or white tabbies from ditto, 13 aln long and 1 1/2 & 1 1/4 wide

- Lot 1561. 1 piece ditto from ditto, 27 aln long & 1 2/4 wide

- Lot 1562. 1 piece ditto from ditto, 21 1/2 aln long & 1 1/4 wide

A different fabric quality, with links to the Anders Berch Collection and the Surat trade, is this fine cotton, named ‘Surate Duties, finest sort ’, a white cotton tabby, which at the cotton manufacturers in Sweden was regarded as providing the best result for fabric printing. Comparable to the white tabbies, repeatedly listed among ‘cotton goods’ in the 1752 action catalogue, above and below. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum… No. 17648b:67a. DigitaltMuseum).

A different fabric quality, with links to the Anders Berch Collection and the Surat trade, is this fine cotton, named ‘Surate Duties, finest sort ’, a white cotton tabby, which at the cotton manufacturers in Sweden was regarded as providing the best result for fabric printing. Comparable to the white tabbies, repeatedly listed among ‘cotton goods’ in the 1752 action catalogue, above and below. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum… No. 17648b:67a. DigitaltMuseum).[left-hand p. 46 aln ≈ 60 cm] ‘Cotton Goods’

- Lot 1563. 1 piece of cotton tabby, 31 aln long 1 1/2 wide & 1 piece of ditto, 18 aln long 2 1/4 wide.

- Lot 1564. 3 pieces of white cotton tabbies, 30 aln long 1 1/2 wide & 2 pieces blue and white ditto, 13 aln long 1 1/4 wide & 2 pieces ditto ditto, 20 aln long 1 1/4 wide.

- Lot 1565. 2 pieces of cotton tabby 31 aln long 1 1/2 wide & 1 piece of ditto, 31 1/2 aln long 1 1/2 wide & 1 piece of ditto, 19 1/2 aln long 2 1/4 aln wide & 1 piece of muslin, 24 1/2 aln long 3 wide & 3 pieces of ‘Chitser’ [chintz – painted or printed calicoes], 7 aln long & 2 pieces of striped cotton tabby, 11 aln long

- Lot 1566-1570. 71 pieces of striped cotton tabbies from Suratte, 11 aln long

- Lot 1571. 1 piece of white cotton tabby, 28 1/2 aln long 1 5/8 wide

- Lot 1572. 12 pieces of striped cotton tabbies from Suratte, 11 aln long

- Lot 1573. 20 pieces of striped cotton tabbies

- Lot 1574. 2 pieces of finer ditto

Whilst, this is one of three preserved pieces of the visibly same 18th century Indian chintz. The fine cotton fabric was painted by hand assisted by wax and mordants to protect the delicate colours. According to the museum’s records at the time of donation in 1944; the fabric had been brought back to Sweden by the East India Company captain Mathias Holmers during the 1760s. A quality which is comparable to the chintzes listed above from the cargo on ‘Götha Leijon’ a decade earlier. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum.… NM.0230821A. DigitaltMuseum).

Whilst, this is one of three preserved pieces of the visibly same 18th century Indian chintz. The fine cotton fabric was painted by hand assisted by wax and mordants to protect the delicate colours. According to the museum’s records at the time of donation in 1944; the fabric had been brought back to Sweden by the East India Company captain Mathias Holmers during the 1760s. A quality which is comparable to the chintzes listed above from the cargo on ‘Götha Leijon’ a decade earlier. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum.… NM.0230821A. DigitaltMuseum).Christoffer Henrik Braad’s journal kept during this voyage registered a multitude of observations too, which included trading possibilities linked to the desirable cotton fabrics, trading networks, other textile wares and European merchants. From the circa six-month-stay in Surat, all sorts of products for domestic and export were looked at closely. Trade in textiles and in particular cotton are informative and gives intricate details of such lucrative commerce for many parties along well-established trade routes. Due to the rare content of this Swedish handwritten journal – revealing details of the long-lived traditions of textile trade – these text sections will be presented via Braad’s own words, in an English translation for the first time (pp. 234-36):

- ‘Among the principal Goods, to be found in Surat, and to the smallest part are produced here, including foremost all sorts of Fabric, thereof they of Silk which mostly come from Amadabath and the inner parts of the Country of Indostan [Hindustan/Indian subcontinent], which are painted Fabrics, Plain or with gold woven inserted Atlas, Taffetas, Cotornis Skala or Embroidered with gold and silver, Bedcovers and Wall coverings of silk with embroidery, Allegras or half-silks of all sorts etc. Besides one or other sorts of Chinese Silk Goods also, such cloths are not used to be brought here in any quantities, also including their Brocades, which they during the weaving insert with gilded or silvered paper, not to mention the Persian Silk fabrics, which here are regarded as the best and most durable of all manufactured in Asia, and of all other sorts which are brought to Indostan and several Asian countries.

- Raw silk is not for export here, whilst what they thereof own comes from Bengal and is manufactured further up in the Country; on the other hand Cotton, which in Guzurat as well as in particular in the closely situated province of Candoss grows abundantly, which is more than enough for the workers of the Country, likewise as for taking to Bengal, China and other places. It is manufactured yearly in Mogolis Country, in such incredible multitude, where from all sorts of finer and coarser Fabric are made, which they give numerable names, sometimes there are Fabrics so super fine, that they are sold per piece for 4 to 500 Rupees, and can only be purchased by Kings and other high-rankings Persons. The ordinary Cotton fabrics, and those which are mostly purchased in this place, usually are manufactured in the province of Guzurat, and above all, it is estimated that the unbleached, used for embroidery, which later is bleached in Brotschna, due to that the water in the River Narbada is regarded as particularly suitable for this here; they are all sold after Corsch for 20 pieces on a Corsch, and is transported early during the northern Monsoon period in parcels. Consisting of 10 Corsch in a parcel to Surat, where the Negotiators, who have the goodness to receive and duty to control the fabrics, and to be responsible for that no differences in width, light or finesse exist, which often is the case, and the finer sorts make a considerable difference to the price.

- Bengal Cotton Fabrics, also constantly arrive by ship in February and March, including substantial amounts of all sorts, with a multitude of names. Additionally, they here have, besides from Guzurat, rather coarse Chitser, bedcovers, skirts, and similar painted and printed fabrics, also sufficient from Masulipatam, which due to its vivid colours and fitness is regarded as one of the most beautiful in India. Their Koraitre, which is folded around turbans, and some are very fine, are made in great numbers around Cambay, just as the so-called Orras, Embroidered fine cloth, by women mostly used to cover their face. From this mentioned and also from Vetapour, arrive Embroidered Blankets, woollen Wall covers as well as other sorts. The domestic goods are nothing compared to the Kashmir Shawls or the previously mentioned broadcloths, which they use to throw over the shoulder or around the Turban in cold weather. These are mostly manufactured of the finest Carmenian wool and at times of the hair, which grows on the chest from a sort of Tibetanian wild goat; whereof various colours are added, with half an aln [≈30cm] embroidery on the border; these are extraordinarily fine and soft as well as very warm and made in many designs, costing from 20 to 6- or 800 Rupees each, despite much knowledge and intricate work in other places, nothing can be compared in fineness to these textiles, which are coming from the mentioned location.

- Spinning is also made in Candoss and Guzurat, to large amounts of Cotton yarn, which to some extent goes to Mocha and Persia and some to Europe. One experiences its fineness and some of it is quite costly, meaning that those who are involved in this commerce, have many troubles searching through all parcels so that no skeins are mixed in, which are coarser, even if the risk is regarded as low, but if so makes a great loss for an unsuspecting buyer, when they in their turn later sell the goods to some who have their eyes more open.'

Some other links to the textile trade as observed by Braad during his time in India in 1751 (pp. 253-76) will be mentioned more briefly. In particular, the commerce via caravan routes (later named the Silk Road) took place at towns along the route and towards the Arabian countries in the eastern Mediterranean; which included raw silk, exquisite cotton of all sorts, gold- and silver fabrics, turbans, indigo, velvets, taffetas, fine wool, etc. The journal gives overall a multitude of examples of the complex trade taking place over land as well as via sea routes between numerous places in Asia and Europe. All these crisscrossing of goods, intertwined in the shipping trade, with the European East India Companies as some of many other involved parties. It must also be emphasised that lucrative and desirable goods, often changed hands several times, for instance, mentioned above when it concerned cotton yarn. Additionally, Braad’s journal informed about the Coromandel coast and particularly from the Bengal area, where among others 1, 2 or 3 Arabian merchant ships arrived each year; to deliver cotton yarn and cochineal for dying red (together with other Arabian and Persian goods) used here for the manufacturing/weaving of fine kinds of cotton in the area. Whilst, the return voyages of these ships were loaded with fine cotton cloths, silks, saltpetre, wax, lack etc.

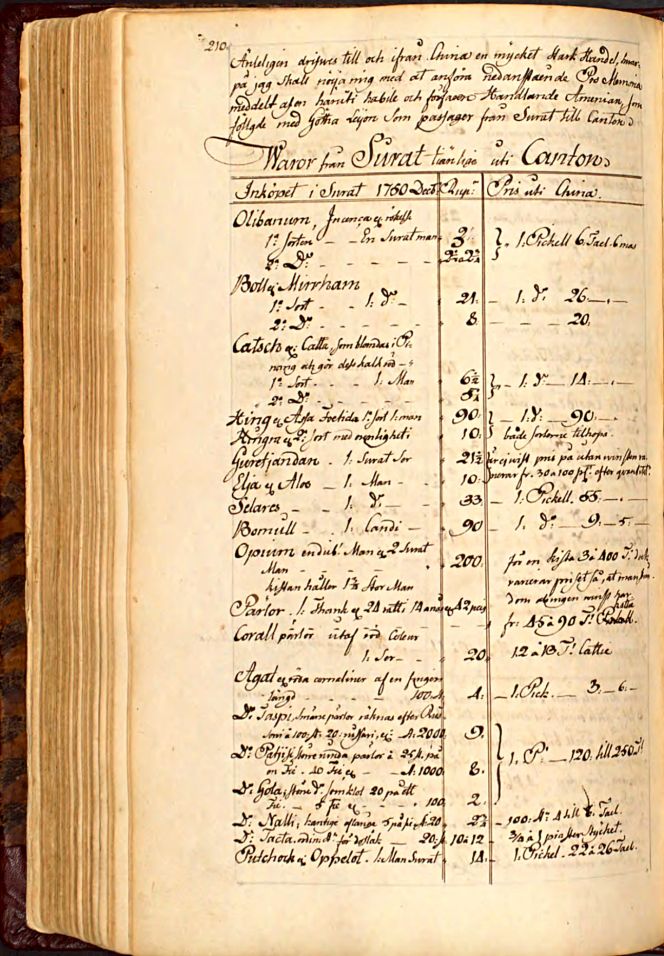

Christoffer Henrik Braad’s journal included a list of ‘Goods from Surat suitable for sale in Canton’, stretching over two pages – whereof textile goods and dyes foremost were Cotton, Grano Cochineal, alum and a small number of silks. His journal explained: ‘The ships usually sailed in early May from Surat and anchored at Canton in December, so they in early March can be back in Surat again, at a time when all the English, Dutch and private seafarers most often are here at the same time.’ (Courtesy of: Göteborg University Library…H 22: 3 D, p. 260).

Christoffer Henrik Braad’s journal included a list of ‘Goods from Surat suitable for sale in Canton’, stretching over two pages – whereof textile goods and dyes foremost were Cotton, Grano Cochineal, alum and a small number of silks. His journal explained: ‘The ships usually sailed in early May from Surat and anchored at Canton in December, so they in early March can be back in Surat again, at a time when all the English, Dutch and private seafarers most often are here at the same time.’ (Courtesy of: Göteborg University Library…H 22: 3 D, p. 260).Another handwritten document, which was instead linked to references and consultations about commerce onboard Götha Leijon was a so-called ’Rådplägningsbok’. For instance on 1 February 1751, during the stopover in Surat, difficulties linked to the commerce in raw cotton were the focus. The text was signed by the supercargoes Anders Gotheen and John Chambers together with three other individuals of commerce:

- ‘Regarding the substantial shortage, poor quality and great expense of Cotton in this place, and that no loading of it could be received until the beginning of May, meaning that our ship could not be ready to sail from here; and in addition a rather high price on all other goods for the Chinese [market], which originate in the large purchases via the English and Dutch ships; we have decided to leave from here at the first opportunity to sail along the coast of Mallabar, so we are not staying here too long preventing us to go there. Which in the month of May is not possible. Where to look out for a good Mallabar loading [of cotton], which is considered better than in Surat, in regard to the large amounts which the other Nations bring from here.’

In conclusion with Braad’s journal, it can be emphasised again that the competition in trade was constantly ongoing, due to the many nations involved in Surat. Foremost the British, Dutch, Moorish, Portuguese, Danish, Swedish, Armenians and ships belonging to the Indian subcontinent. His observations continued further with descriptions of everyday life, plants, historical events etc of Surat before the ship sets sail towards China. The observations followed the voyage itself in great detail, but when they arrived at the road of Wampoo on 6 July 1751, the six months stopover at Canton was excluded in his writing and he only referenced this trading city, from descriptions made in a journal during his previous voyage with the Swedish East India Company in the late 1740s.

Notice: Original documents – in the form of auction catalogues, reference books and journals have been transcribed and translated from Swedish to English by the author of this essay. Digital sources mentioned below, have been added with page numbers = digital page numbering. Specialist terms of fabric qualities have been assisted by Sven T. Kjellberg’s in-depth research of the Swedish East India Company and such terms have also been translated by the author of this essay. The second part will be describing the trade in Chinese silks on the same voyage.

Sources:

- Göteborg University Library (Göteborgs universitetsbibliotek), Sweden: Svenska ostindiska kompaniets arkiv. H 22:4A. ‘Rådplägningsbok för skeppet Götha Leijon' 1750-1752 & H 22: 3 D ‘Beskrifning på skeppet Götha Leijons resa’ 1750-1752 (digital documents).

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, 8 volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Volume Seven: Olof Torén’s journal in letter form).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 116 & 125-131. Olof Torén’s chapter: includes textile observations from other perspectives too – linked to his voyages).

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textilis Essays. ’18th Century East India Textile Trade – A Study of imported Merchandise to Sweden’: No: CIV | April 4, 2019.

- Kjellberg, Sven T, Svenska Ostindiska Compagnierna 1731-1813, Malmö 1974 (pp. 81-116 & 251-257).

- Kommerskollegiet’s Archive, Riksarkivet, Stockholm, Sweden: The Swedish East India Company – sales catalogue. 1752 Götha Leijon (digitised by Warwick Digital Collections).

- Stavenow-Hidemark, Elisabet, ed. 1700-tals Textil – Anders Berchs samling i Nordiska Museet, Stockholm 1990.

- Söderpalm, Kristina, ‘Skeppsjournaler från SOIC:s seglation’, Sverige och svenskarna i den ostindiska handeln – I, pp. 31-96, Göteborg 2016.

- The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. | DigitaltMuseum: Three fabric samples with historical information.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE