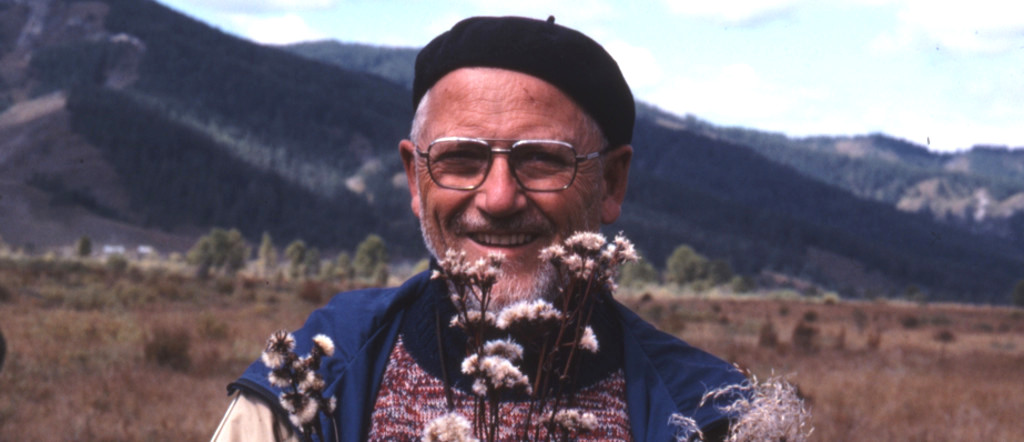

William A Weber holding Ptilagrostis cf. porteri and Saussurea sp., Yabagan Pass, Altai, 1978. Photo by Ivan Krasnoborov, W. A. Weber collection.

The extraordinary compilation of the Linnaeus Apostles will mean different things to different readers. It has enabled me to recognise my small part in the continuing saga of my chosen science of plant taxonomy and phytogeography.

I was born in 1918 and raised in New York City, with several health problems that restricted my acivities, but at age four I was introduced, by a cousin lepidopterist, to a small microscope and learned to raise

Amoeba,

Paramecium,

Euglena, and

Vorticella. I decided I would be a naturalist.

In my childhood I was fortunate to develop interests in ornithology and botany. The Great Depression made it impossible for me to go to Cornell University, so I settled on botany as a career. I was fortunate to benefit from the help of several mentors, and in 1937 I had a chance to work my way through college at Iowa State University, thanks to President Roosevelt’s National Youth Administration program. From 1930 to 1940 I had the opportunity to do field work in New England and Iowa. In 1941, my graduate work took me to Washington State University, the Canadian Rocky Mountains, Oregon, and Idaho. My studies of several genera of Compositae took me to all of the western U. S. My masters program consisted of curating the enormous botanical collections of Wilhelm Nikolaus Suksdorf (1850-1932), transcribing his field notes (in old German script), typing his labels, and publishing a short biography and his itinerary of fifty years of collecting. By the time I received the PhD in 1945 I was very well acquainted with the floras of most of the United States.

In 1946 I was able to get a position in the Biology Department at the University of Colorado. There was a Museum. When I met the Director, he asked me, “What do you want to do here?” I told him, “I would like to build an herbarium.” He answered, “Do we need one?” The rest is history. In 1962, I became full time curator of the herbarium in the University of Colorado Museum.

I have had many opportunities to botanize abroad, often by invitation: Russia, the Altai, the Alps, the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Greece and Crete, Japan, Canary Islands, Mexico, Antarctica, Nepal, and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, Fenno-Scandia, Europe, Papua New Gunea, Australia. After almost seven decades, the University of Colorado has a great and balanced herbarium of a half million specimens of all groups of plants, with substantial world coverage.

“

Linnaeus seemed to infuse Sweden with a

knowledge of natural history tradition and history

that became part of everyday life.

”

The most significant event in my life was my entry into lichenology in 1951. In a small library of books purchased from a colleague I found in a book by Hugo Magnusson on the lichens brought back to Uppsala by the Sven Hedin expeditions to Middle Asia several illustrations that convinced me that some of them were species I was finding in Colorado, and I needed to compare them. In 1957 I was able to take a sabbatical in Sweden, and worked in the herbaria in Stockholm, Lund, and Uppsala for a year. The experience was not only my own, but a defining one for my wife and, in particular, our three daughters, who all attended Swedish schools. Linnaeus seemed to infuse Sweden with a knowledge of natural history tradition and history that became part of everyday life. Olaf Selling, a Linnaeus specialist, took us to Hammarby, where we visited the house and garden of Linnaeus, and his herbarium building, where I was able to have myself photographed at Linnaeus’ lectern.

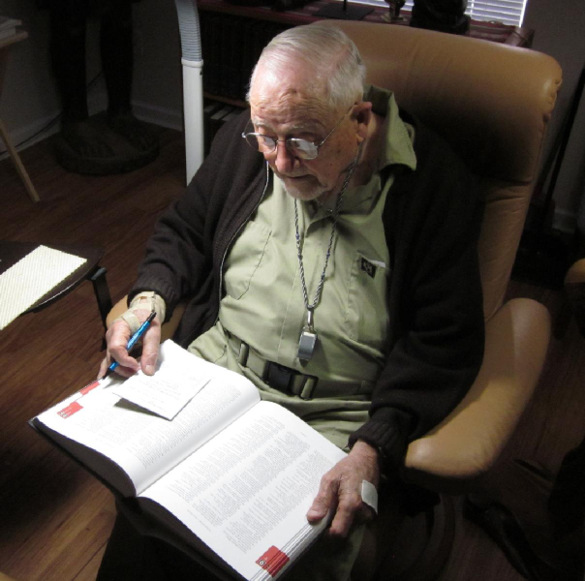

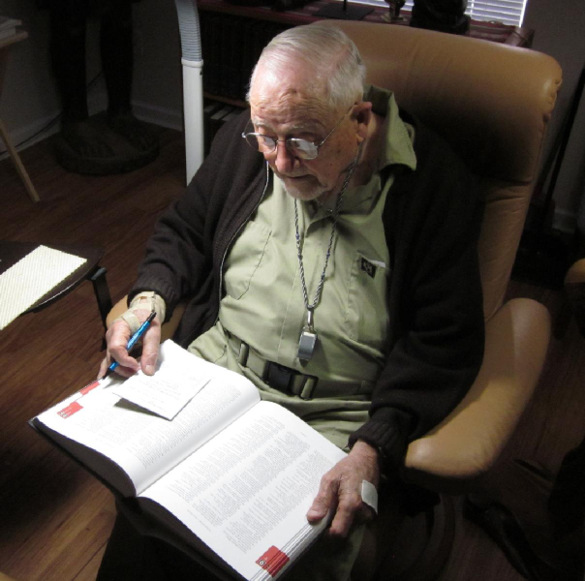

William Weber at home with The Linnaeus Apostles Global Science & Adventure, Volume Eight (The Encyclopaedia). Photo by Ronald C. Wittmann.

I frequently visited Uppsala, Lund, and Göteborg, and was able to examine the botanical gardens, the herbaria of Acharius, Fries, Thunberg, Queen Louisa Ulrika, and the great collection of lichen exsiccati. I was fortunate to get to know personally the leaders of lichenology and bryology: Rolf Santesson, Ove Almborn, Gunnar Degelius, Hugo Magnusson, Eilif Dahl, and Einar Du Rietz. A midsummer excursion to Skåne and Öland brought us to Småland where we visited Linnaeus’ Råshult. On the coast my one of my daughters became fascinated by the algae, and we walked through the village looking for appropriate paper to use for collecting. We had no success until a storekeeper said, “Oh, why didn’t you ask for herbarium paper? All the shops carry it!” Where else in the world but in Linnaeus’ country?

From that time on I have been constantly in touch with European and Asian colleagues. In fact, the Colorado tundra has brought them here: Leena Hämet-Ahti, Teuvo Ahti, Ove Almborn, Per Jørgensen, Dharani Awasthi, Eilif Dahl, Hannes Hertel, Kjeld Holmen, Eric Hultén, Olle Mårtensson, Herman Persson, Erling Porsild, Karl Rechinger, Hugo Sjörs, Alexei Skvortsov, Einar Timdal, Tor Tönsberg, and Antero Vaarama.

Over the years, I began to realize that the southern Rocky Mountain flora had numerous species in common with Middle Asia, and chancing to read the autobiography of Sir Joseph Hooker, I learned that in 1877 he spent five days in the Colorado alpine with Asa Gray and was struck by the large number of species that were shared between Colorado and the Altai. I was able to find the list of plants he collected, and ultimately found that the connections involved lichens and bryophytes, as well as vascular plants. I had the opportunity to spend two field seasons in the Altai, and three in the Nepalese Himalaya, solidifying our knowledge of this element and ultimately publishing on the subject in depth.

Alfred Russel Wallace visited Colorado in 1883 and spent two days at Gray’s Peak with a young schoolteacher, Alice Eastwood. Because he saw a number of species he was familiar with in England, he surmised that the alpine flora of the circumboreal southern mountains must have been native to the Arctic, but had migrated south by the spreading glaciers, and survived by climbing the mountains. This is the interpretation that still pervades the literature and the schoolroom. I propose, on the contrary, that the alpine floras are older, probably dating back to continuous populations in the Tertiary. The similarities of the southern Rockies with the Altai have nothing to do with migration, but with subsequent fragmentation of ancient distribution patterns. This I leave to future generations to verify or disprove, just as Linneaus’ apostles left their ground-breaking work for others, including myself, to build on.

Returning to the

Linnaeus Apostles, I delighted in the fabulous index volume while thinking back on the myriad stimuli the apostles’ adventures had brought me. Just how good is this index? I was curious - could I find a very specific item mentioned only briefly in one of the early volumes? I was able to locate it quickly in volume 1, page 355.

“In 1813 Einar Lönnberg writes in his notes to these [Linnaeus’] instructions that Linnaeus had such a herbarium of mounted fish, which he assumes must have gone to London with the other Linnaean collections.”

Linnaeus prepared fish specimens, dispensing with costly, bulky jars, and spirits that evaporated over time, by drying them enough to remove the skins, which he then mounted like plant specimens on herbarium sheets. He treated these against moths with terpentine and herbs. This technique was known to the Apostles.

When I was in London to receive the FLS in 1984 I was taken into the bomb shelter where Linnaeus’ herbarium was kept, and I was shown those fishes!

As I relished each volume of The Linnaeus Apostles cover to cover, I marvelled at how their lives and ours are braided together.

Boulder's iconic rock formations, the Flatirons as seen from Fairview High School. Source: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

William Weber at home with The Linnaeus Apostles Global Science & Adventure, Volume Eight (The Encyclopaedia). Photo by Ronald C. Wittmann.

William Weber at home with The Linnaeus Apostles Global Science & Adventure, Volume Eight (The Encyclopaedia). Photo by Ronald C. Wittmann.

Sveaskog, Stockholm, Sweden

Sveaskog, Stockholm, Sweden