ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

18TH CENTURY HANDKERCHIEFS

– The Swedish East India Company Trade

The aim of this essay is to focus on a small branch of the Swedish East India Company dealing in fabrics used for handkerchiefs. Observations from my earlier research related to Carl Linnaeus and his “Apostles”, a hand-written Swedish account book from one of the Company’s ships and preserved pieces of cloth, will give some evidence for such goods. 18th century handkerchiefs seem overall to have been an accessory that was worn out – the most natural cause for its rarity – or dropped, used for various purposes as collecting insects/plants, given away or even stolen according to notations in some travelling accounts and journals from the 1740s to 1760s.

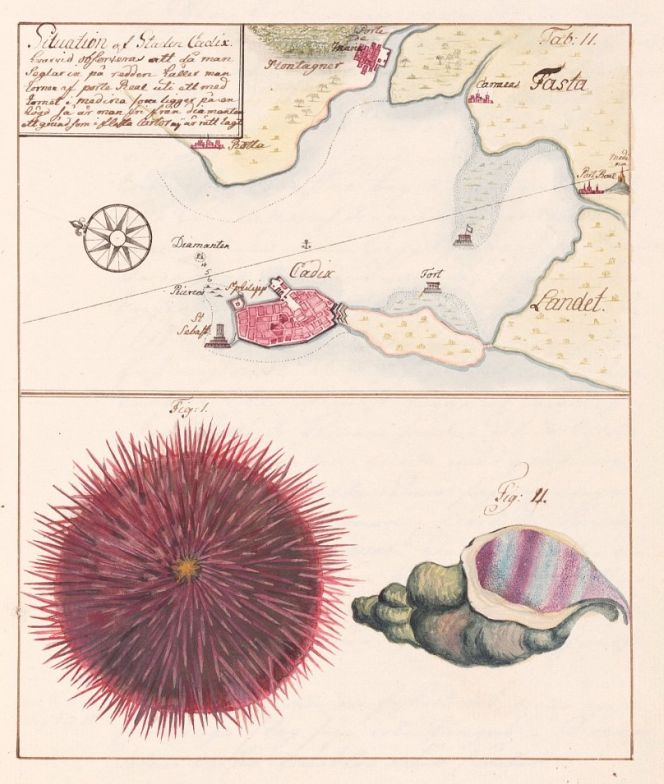

This map, illustrated in the East India traveller Carl Johan Gethe’s journal (1746-1749), is of the ideally sheltered harbour of the city of Cadix, where many of the Swedish East India Company ships lay at anchor in order to replenish their stores and carry out trade. The Linnaeus’ apostle Olof Torén’s first voyage stopped over there in 1748; the apostles Pehr Osbeck (1750) and Christopher Tärnström (1746) spent several months in Cadix and its environs on their way to China. (Courtesy of: National Library of Sweden, M 280, p. 29).

This map, illustrated in the East India traveller Carl Johan Gethe’s journal (1746-1749), is of the ideally sheltered harbour of the city of Cadix, where many of the Swedish East India Company ships lay at anchor in order to replenish their stores and carry out trade. The Linnaeus’ apostle Olof Torén’s first voyage stopped over there in 1748; the apostles Pehr Osbeck (1750) and Christopher Tärnström (1746) spent several months in Cadix and its environs on their way to China. (Courtesy of: National Library of Sweden, M 280, p. 29). 18th century handkerchiefs are sometimes mentioned in contemporary hand-written letters, travel journals or account books connected to the Swedish East India Company trade. One reason for repeated mentions of such an accessory appears to be its multiple functions. Handkerchiefs were connected to sadness and emotions, snuff-taking, and practical uses like wrapping up plants or catching insects, a beautiful present or invaluable during illness. It came in varied designs, such as one colour only, striped, checked, or woven in more advanced diaper techniques or with printed patterns. The materials were either silk, cotton or linen – sometimes embellished with laces and embroidery. Silk has always been associated with costliness, but even cotton was still regarded as a luxury material in mid-18th century Sweden. It may also be noted that the limited amount of fabric needed for a small handkerchief, made it reasonable in price for a wider society. Judging by artworks of the period, this useful piece of fabric was usually tucked away in a pocket or concealed in some other way – probably due to traditions or practicality or etiquette.

It is rare to find preserved 18th-century textiles in Sweden of this category, and if so, it is hard to find evidence of any origin from the East Indies. Fine woven pieces of cotton or silks may, for instance, originate from the East, and later on, the patterning was printed by a Stockholm manufacturer and thereafter sold for local or national consumption. Another possibility was that the raw material was imported, and the cloth was woven as well as printed by Swedish manufacturers, which for many years was preferred by the country’s mercantile economy and widely extended sumptuary laws.

![Prices for ‘Näsdukar’ [handkerchiefs] were listed in gold Ducats, Spanish piasters and Chinese taels in double entry bookkeeping. This currency calculation was included in an Account book for the ship “Stockholms slott” within the Swedish East India Company, 1762-1763. The return goods on this voyage from Canton in China to Göteborg (Gothenburg) in Sweden were mainly porcelain, tea, lacquer-work and ‘handkerchiefs’ – as was registered on this particular page. In the main originating from Canton, with an exception of Bengal in India. Named as ‘Canton Single Cloths’, ‘Canton double Cloths’, ‘Bengal cloths’ etc. These cloths for handkerchiefs were presumably marked with differing colouring at regular intervals already during the weaving process, to be cut into the acquired number of handkerchiefs at arrival. Either by the East India Company traders in Göteborg themselves or sold on in full length to merchants or private buyers in Sweden. (Courtesy of: Maritime Museum, Stockholm, Sweden, SH 511:24).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/2-nacc88sdukar-1762-63-900x699.jpg) Prices for ‘Näsdukar’ [handkerchiefs] were listed in gold Ducats, Spanish piasters and Chinese taels in double entry bookkeeping. This currency calculation was included in an Account book for the ship “Stockholms slott” within the Swedish East India Company, 1762-1763. The return goods on this voyage from Canton in China to Göteborg (Gothenburg) in Sweden were mainly porcelain, tea, lacquer-work and ‘handkerchiefs’ – as was registered on this particular page. In the main originating from Canton, with an exception of Bengal in India. Named as ‘Canton Single Cloths’, ‘Canton double Cloths’, ‘Bengal cloths’ etc. These cloths for handkerchiefs were presumably marked with differing colouring at regular intervals already during the weaving process, to be cut into the acquired number of handkerchiefs at arrival. Either by the East India Company traders in Göteborg themselves or sold on in full length to merchants or private buyers in Sweden. (Courtesy of: Maritime Museum, Stockholm, Sweden, SH 511:24).

Prices for ‘Näsdukar’ [handkerchiefs] were listed in gold Ducats, Spanish piasters and Chinese taels in double entry bookkeeping. This currency calculation was included in an Account book for the ship “Stockholms slott” within the Swedish East India Company, 1762-1763. The return goods on this voyage from Canton in China to Göteborg (Gothenburg) in Sweden were mainly porcelain, tea, lacquer-work and ‘handkerchiefs’ – as was registered on this particular page. In the main originating from Canton, with an exception of Bengal in India. Named as ‘Canton Single Cloths’, ‘Canton double Cloths’, ‘Bengal cloths’ etc. These cloths for handkerchiefs were presumably marked with differing colouring at regular intervals already during the weaving process, to be cut into the acquired number of handkerchiefs at arrival. Either by the East India Company traders in Göteborg themselves or sold on in full length to merchants or private buyers in Sweden. (Courtesy of: Maritime Museum, Stockholm, Sweden, SH 511:24).A decade earlier, from 1750 to 1752, the Linnaeus’ Apostle Pehr Osbeck worked as ship’s chaplain on another Swedish East India Company ship destined for Canton. For instance, in the trading stores, it was possible to buy single pieces of woven cloth for the private use of the Chinese as well as the Europeans. That was best done ‘in the porcelain street, which is the broadest in the whole town…’ where one could buy silk fabrics, silk stockings, handkerchiefs, ribbons and cotton cloth in September 1751. In the same year, he also listed all sorts of goods that could be purchased in Canton, including handkerchiefs and some enlightening notes about imported fabrics from India via the British East India Company. ‘…Quilts, cotton-tick at four or five mess, stockings, handkerchiefs, &c. are plentiful here…Fine chintz, Madras linen, Madras handkerchiefs, &c. are likewise to be had at Canton; the English ships bring them to that place; but they are very dear, since they are second or third-hand goods.’

Another of Carl Linnaeus’ Apostles who also worked on a Swedish East India Company ship as a chaplain was the somewhat earlier Christopher Tärnström. Even if he sadly died on the way to Canton on Pulo Condore (Côn Sơn Island) in 1746, he made a detailed note about handkerchiefs in the form of presents. This was reflected in some notes on the life onboard in the Javanese archipelago and revealed details of his own private belongings and the manner in which the time might be passed on an East India ship. The island of Lucipara was a welcome spot for the priest as it was the custom on these ships for the officers to give all kinds of small gifts to the chaplain onboard when passing the place. Among the many gifts of food and drink were also to be found some ‘beautiful and pretty handkerchiefs and caps’ (13 Sept. in 1746). Those were probably made of the finest silk or cotton.

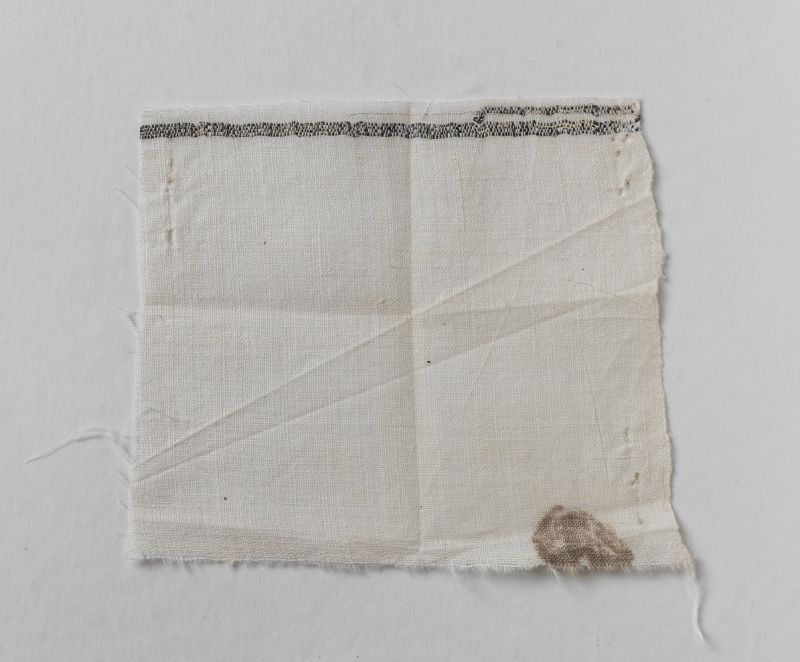

This is a quality of fabric which is part of the sample collection gathered by the economy professor Anders Berch around the 1750s-1760s and linked to the Surat trade of the Swedish East India Company. A fine cotton, named ‘Surate Duties, finest sort’, a quality which at the cotton manufactures in Sweden was regarded as providing the best result for fabric printing. Handkerchiefs were one of several possible uses for such fine cottons added with fashionable prints. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. No. 17648b:67a).

This is a quality of fabric which is part of the sample collection gathered by the economy professor Anders Berch around the 1750s-1760s and linked to the Surat trade of the Swedish East India Company. A fine cotton, named ‘Surate Duties, finest sort’, a quality which at the cotton manufactures in Sweden was regarded as providing the best result for fabric printing. Handkerchiefs were one of several possible uses for such fine cottons added with fashionable prints. (Courtesy of: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. No. 17648b:67a).A third Linnaeus’ Apostle, Pehr Kalm, was not part of the Swedish East India Company travels, but as an informative comparison, he kept a meticulous travelling account during his journey via Norway and England to the North American colonies from 1747 to 1751. Among many necessary items and clothing needed, he purchased handkerchiefs in London on more than one occasion. The origin of the purchase is unknown, probably English woven fabrics, but even East Indian qualities are a possibility.

- 13 February 1748. One cotton handkerchief, 1Sh. & One Silk handkerchief, 3Sh.

- 16 March 1748. Silk handkerchief, 5Sh.

- 22 April 1748. Silk handkerchief, instead of the one that was stolen, 3Sh. 6d.

The three purchases give several facts of interest. Silk qualities were more expensive than cotton, as may be expected, but the one bought on March 16th, which later on got stolen, was the most costly one. It seems like this particular item was of a more luxurious kind, and Kalm replaced it with an “ordinary” silk quality, either for cost-saving reasons or to avoid a new theft of an eye-catching handkerchief.

Sources:

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007- 2012 (Volume Seven: Journals of Pehr Osbeck & Christopher Tärnström).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 126-128, 409, 435-439).

- Maritime Museum in Stockholm, Sweden (SH 511:24, page in Account book 1762-1763. The quotes of handkerchiefs, Oct. 1762-Jan. 1763, in translation from Swedish).

- National Library of Sweden, Map from ‘Dagbok hållen p. Resan till Ost Indien, Begynt den 18 octobr: 1746 och Slutad den 20 Juni 1749’ by Carl Johan Gethe (M 280, p. 29).

- Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. (Anders Berch Collection, No. 17648b:67a).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE