ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

A HANDICRAFT ORGANISATION: 1914 to 1960s

– Inspiration and Reconstruction of Traditional Textiles in Sweden

At the outbreak of the war in 1914, the “textile golden age” in Sweden, which had lasted since around 1890 with the Art Nouveau style and National Romanticism, came to an abrupt end – a simpler trend was emphasised in many respects. However, this historical development had minor implications for Malmöhusläns Hemslöjdsförening (Handicraft Organisation of Malmö County) at the time. Primarily due to that, the organisation, in most of its work, was still mainly inspired by the country people’s 18th- and 19th-century textile patterns and techniques. This essay will also look closely at the continuous period up to the 1960s, when educational needlecraft and weaving became deeply intertwined with local communities, simultaneously as exhibitions and publications aimed at a wider geographical audience. Reconstructions, inspirations from regional material culture, and ideas for new designs went hand in hand with this active handicraft organisation over many years.

-800x589.jpg) The publishing work “Gammal Allmogeslöjd” – in eight folio-sized instalments – is a unique record and visual documentation of the traditional art of woven and embroidered household textiles by rural communities in the western parts of Skåne province, Malmöhuslän/Malmö county. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

The publishing work “Gammal Allmogeslöjd” – in eight folio-sized instalments – is a unique record and visual documentation of the traditional art of woven and embroidered household textiles by rural communities in the western parts of Skåne province, Malmöhuslän/Malmö county. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.The first section of this publishing work was printed in 1916, with the final part released in 1923. This historical documentation was conducted in domestic settings across all districts of the region, through detailed descriptions and photographs of each object, gathered from interviews with the current owners of the textiles. These interviews have become especially valuable, as owners from the 1910s and 1920s often maintained direct ties to the traditional culture of their inherited textiles, whether from parents and grandparents or through other sources of knowledge about provenance. The woven carriage cushions, linen bobbin lace, woollen embroideries, and other cherished objects made during the 19th century – or even earlier – could thus be placed within their historical and social context. All this collected information has uncovered numerous facts about individual weavers and embroiderers, their lifestyles, the intended audience of these textiles, and how the objects have been cared for over generations or, at times, includes descriptions of the circumstances surrounding auctioned items.

In keeping with the same spirit, since the organisation's founding in 1905, their activities included selling handcrafted goods, lotteries, weaving courses, documenting local textiles, and organising exhibitions. Notably, the exhibition section grew stronger after the Baltic Exhibition in 1914, with thirty-two exhibitions held until 1925. Most of these textile displays were local, but also with exhibitions in Stockholm, Göteborg, and København, as well as further afield in London, Paris, Basel, Zürich, and Helsinki. One of the largest exhibitions in which the Malmö handicraft organisation participated was The International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris in 1925. At this event, art-woven textiles and whitework embroidery were displayed. Despite these international engagements, the local perspective was chiefly shaped by three leading women – Lissi Möller (1864-1926), Ebba Billing (dates unknown), and Henriette Coyet (1859-1941). Möller served as the organisation's director, Billing published a book on natural dyeing and organised weaving courses, while Coyet was the principal editor of the extensive publication “Gammal Allmogeslöjd” illustrated above.

At the Stockholm Exhibition in 1930, the Handicraft Organisation of Malmö County showcased reconstructions of 19th-century art, including woven cushions, bedcovers, and modern furnishing textiles. These new designs had grown in popularity during the previous decade, especially appealing to the upper-middle class with money to spend and for public settings – to furnish with fabrics from Handicraft Organisations became a mark of good taste. | Aerial photograph of the Stockholm Exhibition 1930 by Gustaf W:son Cronquist. (Collection: Arkitektur- och designmuseum, ARKM.1990-106-006. DigitaltMuseum. Photo. Public Domain).

At the Stockholm Exhibition in 1930, the Handicraft Organisation of Malmö County showcased reconstructions of 19th-century art, including woven cushions, bedcovers, and modern furnishing textiles. These new designs had grown in popularity during the previous decade, especially appealing to the upper-middle class with money to spend and for public settings – to furnish with fabrics from Handicraft Organisations became a mark of good taste. | Aerial photograph of the Stockholm Exhibition 1930 by Gustaf W:son Cronquist. (Collection: Arkitektur- och designmuseum, ARKM.1990-106-006. DigitaltMuseum. Photo. Public Domain).The Handicraft Organisation continued hosting exhibitions throughout the 1930s, especially in 1937, a year filled with several such events. The International Exposition of Art and Technology in Modern Life in Paris, from May to November, became the focal point not only for the Malmö organisation but also for Swedish handicraft and design at a time when “Swedish Modern” gained international recognition. Locally, an exhibition at the Agricultural Show in Malmö received high praise from textile historian Elisabeth Thorman (1867-1961) in the magazine Svenska Slöjdföreningen tidskrift (1937). She reflected on the event, saying: ‘It is sufficient to emphasise that neither one nor another woven fabric quality nor exquisite embroidery dominated; the tapestry (flamsk) alone filled one large hall, and woollen embroidery another. The splendour was incomparable. Whitework of pure, sacred, spiritualised beauty filled the third hall. Never before has the country people’s textile art of Skåne province maintained its prestige as it did this time.’ However, another exhibition organised by the same handicraft organisation received some negative reviews. It was the art historian Gerda Boëthius (1890-1961), who, in the same magazine in 1937, commented from the Liljevalchs Art Gallery in Stockholm: ‘…the reconstructions of the tapestries (flamsk) and double interlocked tapestries (rölakan) are poor in colour and will not be acceptable as copies.’

During the entire interwar period, there was considerable interest in the influences of traditional textiles once produced in the farming communities of Skåne province. However, opinions diverged more sharply during the 1930s, as increasing numbers of textile artists advocated for more modern and up-to-date designs. Nonetheless, this was not entirely a new idea, as the renowned textile artist Elsa Gullberg (1886-1984) had already demonstrated at the Baltic Exhibition in 1914 that crafted woven furnishings could be used for upholstering for example in Gustavian (Neo Classic) furniture. The magazine Svenska Slöjdföreningen tidskrift frequently included articles and discussions about the purpose of the handicraft movement during the 1930s. Among various topics, art-woven textiles, with their rich patterns and techniques from the southernmost province of Skåne, were one branch of traditional materials encouraged to be supported by the local handicraft organisation. Support came in the form of purchasing ready-made textiles woven by professional handloom weavers from the organisation, yarns, linen, and other materials for personal weaving or embroidery, either as an educational resource through courses for different age groups or via exhibitions. Unlike plain woven fabrics, which textile industries could produce equally well, but more rapidly and at a lower cost.

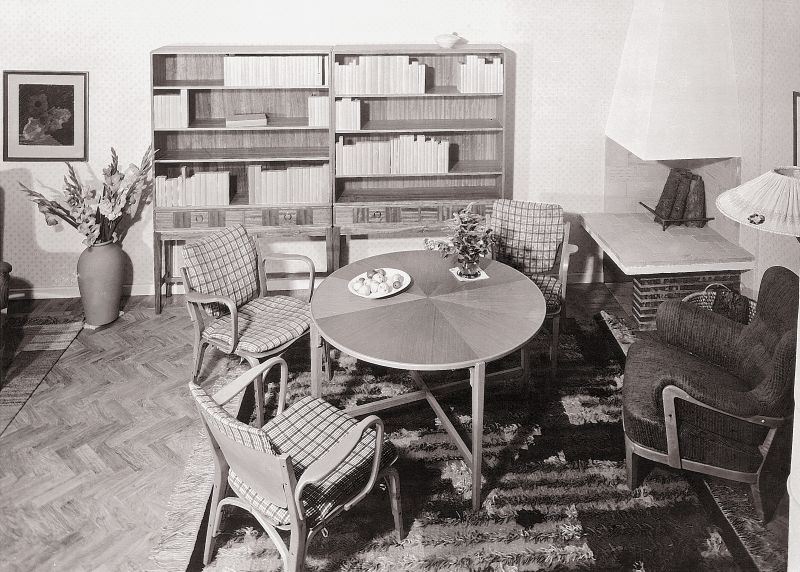

Interior by Svenska Slöjdföreningen (The Swedish Society of Crafts and Design) at the exhibition held in the newly built “Friluftsstaden” in Malmö, 1944. In this picture showing apartment no. 15, the Handicraft organisation of Malmö County was represented with furnishing textiles. (Collection: Photo archive: Form, Sweden. Unknown photographer in 1944. Public Domain).

Interior by Svenska Slöjdföreningen (The Swedish Society of Crafts and Design) at the exhibition held in the newly built “Friluftsstaden” in Malmö, 1944. In this picture showing apartment no. 15, the Handicraft organisation of Malmö County was represented with furnishing textiles. (Collection: Photo archive: Form, Sweden. Unknown photographer in 1944. Public Domain).The local building constructor and designer Eric Sigfrid Persson (1898-1983) collaborated with Svenska Slöjdföreningen during the 1930s and 1940s – an organisation founded as early as 1845 – which organised house exhibitions in some of his newly built homes in Malmö. These exhibitions took place in the multi-storey building Ribershus in 1938 and the terrace-housed area Friluftsstaden in 1944 (illustrated above). Ribershus marked the beginning of nine-storey buildings along the Öresund coastline in the city; the main aim was that all rooms should be bright with large windows and that all apartments in this house must have a coastal view. Likewise, the greenery surrounding the house and the plants in the stairwells were considered of the utmost importance – so residents could experience the sea and nature even whilst living in a high-rising building. In the 1938 house exhibition, contemporary furnishing ideals associated with the functional style (Funkis), characterised by bright, shaded furniture and fabrics without ornamentation or unnecessary embellishments, emphasising simplicity and elegance, were reflected throughout the interiors. Printed cotton was also a popular new trend, preferred for curtains and upholstery.

In 1944, the follow-up house exhibition took place when the construction of Friluftsstaden was completed. Once again, the importance of sunlight for the homes was highlighted with a “sun yard” in front of each terraced house. Equally lush trees, shrubs, and flowering plants were already featured in the architectural plans. The exhibition included fifteen apartments or terraced houses to showcase a variety of living space sizes and designs to meet the needs of different families. All the leading textile firms and designers of the period were present, such as NK, Bruno Mattsson (1907-1988), Barbro Nilsson (1899-1983) from Märta Måås Fjetterström AB, and the previously mentioned Elsa Gullberg, alongside local exhibitors like the Handicraft Organisation of Malmö County. The dominant textiles reflected the style of the 1938 Ribershus house exhibition – focusing on simplicity, style, “green rooms,” and spaciousness – in the form of lightweight cotton curtains, rag or pile-woven carpets, printed cotton, and striped fabrics for furnishings. The Handicraft Organisation of Malmö displayed their products in apartment no. 15, where visitors could see a pile-weave carpet, a checkered rag carpet, white transparent curtains, and wool/linen upholstery fabrics.

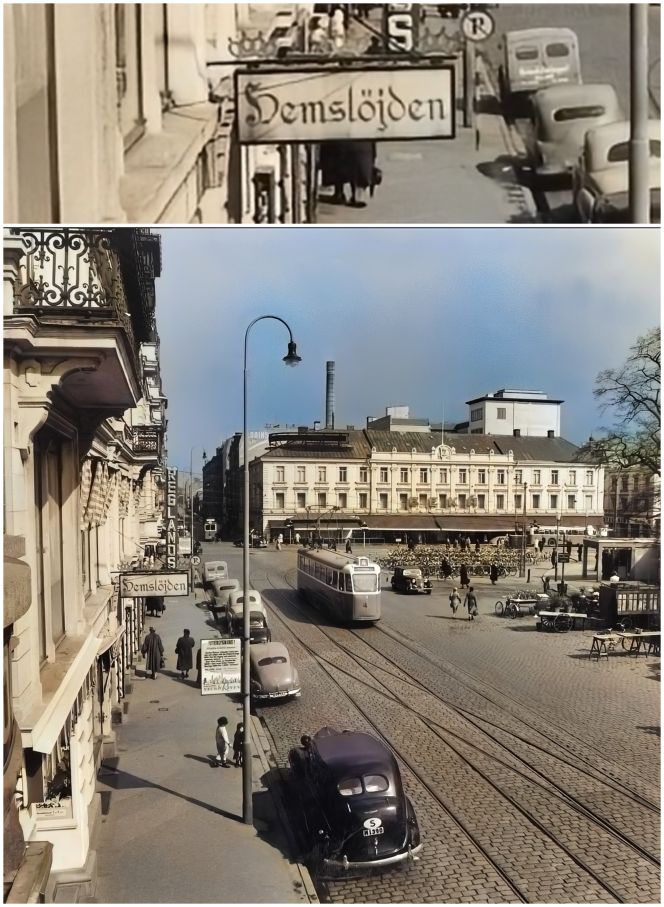

The marketplace ‘Gustaf Adolfs torg’ in Malmö city centre, where “Hemslöjden” was established in 1908, visible via a hanging sign. Noticeable in the picture is also the tall chimney in the background, which was the location for the woollen fabric, “Malmö Yllefabriks AB” founded already in 1867, and its production ceased in 1958, four years after this picture was taken, when the factory still had 700 employees in the textile city of Malmö. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, NMA.0043277. DigitaltMuseum. Photo: Erik Liljeroth & modern digital colourisation).

The marketplace ‘Gustaf Adolfs torg’ in Malmö city centre, where “Hemslöjden” was established in 1908, visible via a hanging sign. Noticeable in the picture is also the tall chimney in the background, which was the location for the woollen fabric, “Malmö Yllefabriks AB” founded already in 1867, and its production ceased in 1958, four years after this picture was taken, when the factory still had 700 employees in the textile city of Malmö. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, NMA.0043277. DigitaltMuseum. Photo: Erik Liljeroth & modern digital colourisation).From 1942 to 1969, Gertrud Ingers (1904-1991) significantly influenced the development of the Handicraft Organisation of Malmö County in her role as director. She grew up in a home where textile handicraft was part of everyday life, and naturally, she was trained to be a weaving teacher as a young woman. This became her main occupation before taking on her role as director. Ingers had an extensive network within the Swedish handicraft movement and was active in various educational branches of needlecraft and weaving. Her involvement was especially notable through organised textile exhibitions and weaving courses, as well as her publications on handicrafts, which included about 30 books and articles. Some of the most popular titles covered linen damask weaving, towels, tablecloths, tapestries, and carpets, along with several instructive embroidery books. Most of these books focused on practical textile art, and on many occasions, she collaborated with textile researchers on the historical sections. Her key associate was the art historian and museum curator Ernst Fischer (1890-1980), who worked at the Malmö Museum from 1925 to 1955. Tapestry weaving, in particular, experienced a revival because many details were selected and rearranged from traditionally woven 18th- and 19th-century bedcovers, carriage cushions, and similar items, woven in the western districts of Skåne province. These smaller weaving projects – intended for wall decorations, cushions, spectacle cases, and more – woven on a linen warp with a woollen weft in a frame placed on a table became extremely popular.

This essay will conclude with two pictures showcasing the type of high-quality embroidery and woven household objects – either sold as part of a handicraft kit including woollen yarn, linen, linen threads, instructive books, etc., or purchased as a finished product, handmade by a professional weaver or embroiderer – found in handicraft shops during the 1950s and 1960s. To some extent, the same textiles remained popular for a longer period and were further inspired by new designs over the following two decades.

This linen damask towel, featuring repeated carnation motifs, was acquired from Malmöhusläns Hemslöjdsförening (the Handicraft Organisation of Malmö County) during the 1950s or 1960s. The professionally handmade towel, measuring 49 cm by 69 cm, was woven by one of the organisation’s female damask weavers on a loom equipped with a shaft draw system. The very delicate warp consisted of a 1-ply bleached and unbleached linen (approximately 24 threads per centimetre), while the weft was spun from a hand-spun linen thread (around 26 threads per centimetre). The use of hand-spun linen for the weft and the hand hemming further emphasised the high quality of this household textile. The towel came into my ownership through inheritance. Due to its exceptional fineness, it has never been used and has always been regarded as a “museum piece”. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

This linen damask towel, featuring repeated carnation motifs, was acquired from Malmöhusläns Hemslöjdsförening (the Handicraft Organisation of Malmö County) during the 1950s or 1960s. The professionally handmade towel, measuring 49 cm by 69 cm, was woven by one of the organisation’s female damask weavers on a loom equipped with a shaft draw system. The very delicate warp consisted of a 1-ply bleached and unbleached linen (approximately 24 threads per centimetre), while the weft was spun from a hand-spun linen thread (around 26 threads per centimetre). The use of hand-spun linen for the weft and the hand hemming further emphasised the high quality of this household textile. The towel came into my ownership through inheritance. Due to its exceptional fineness, it has never been used and has always been regarded as a “museum piece”. (Private ownership). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.![This colourful woollen embroidery on white coarse broadcloth, called “wadmal,” has been stitched with various lengths of satin stitches, “schattersöm,” and stem-stitch, as illustrated in the book ‘Brodera mera,’ published in 1963 by Malmöhusläns Hemslöjdsförening [the Handicraft Organisation of Malmö county]. (Private ownership). Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/6-a-wollen-embroidery-800x600.jpg) This colourful woollen embroidery on white coarse broadcloth, called “wadmal,” has been stitched with various lengths of satin stitches, “schattersöm,” and stem-stitch, as illustrated in the book ‘Brodera mera,’ published in 1963 by Malmöhusläns Hemslöjdsförening [the Handicraft Organisation of Malmö county]. (Private ownership). Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

This colourful woollen embroidery on white coarse broadcloth, called “wadmal,” has been stitched with various lengths of satin stitches, “schattersöm,” and stem-stitch, as illustrated in the book ‘Brodera mera,’ published in 1963 by Malmöhusläns Hemslöjdsförening [the Handicraft Organisation of Malmö county]. (Private ownership). Photo and embroidery: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.The illustrated publication was one of the organisation’s embroidery books, which had multiple purposes. Firstly, it aimed to provide a brief introduction for the embroiderer on historical aspects, materials, tools, preferred laundry methods, and other practical instructions. This is followed by a wide selection of illustrated embroideries in colour or black-and-white, with detailed notes about suitable linen or woollen foundations, yarns, threads, sizes, and used stitches, among other details, as pattern drawings were included on many pages. Secondly, this successful enterprise was also connected to the fact that all materials used in the illustrated embroideries could most easily be purchased from one of the organisation’s shops. Moreover, the books were sold over many years and published in more than one edition. For example, the book Ur skånska syskrin in 1968 was now in its 3rd edition and printed in 30,000 copies, which was an impressive number for a relatively small language such as Swedish.

Note: All quotes have been translated from Swedish to English by the author of this essay.

Sources:

- Boëthius, Gerda, Nordisk Hemslöjd i Liljevalchs konsthall, Sv. Slöjdf. Tidskr. 1937. nr, 8.

- Coyet, Henriette, Skånsk hembygdsslöjd, 1922.

- Fischer, Ernst, Linvävarämbetet i Malmö och det skånska linneväveriet, 1959.

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Fyra sekel Malmö textil – 1650 till 2000, pp. 23-91. Elbogen, 1999.

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Handicraft and Textile Exhibitions – A Case Study from 1900 to 1914’, iTEXTILIS. No: XCVII | September 27, 2018.

- Hansen, Viveka (ownership of illustrated textiles and books).

- Ingers, Gertrud & Becker, John, Damast, Västerås 1955.

- Johansson, Gotthard & Stavenov, Åke, Vi bo i Friluftsstaden, Sv. Slöjdf. Tidskr. 1944.

- Malmöhusläns Hemslöjdsförening, Gammal Allmogeslöjd, Malmö 1916-23 (2nd ed. 1951).

- Malmöhusläns Hemslöjdsförening, Malmöhusläns Hemslöjdsförening 1905-1925, 1926.

- Malmöhusläns Hemslöjdsförening, Brodera mera, 1963.

- Malmöhusläns Hemslöjdsförening, Ur skånska syskrin, 1968.

- Malmöhusläns Hemslöjdsförning, Malmö, Sweden. (Long-term personal experience of this Handicraft Organisation, due to my apprenticeship period and work, 1979 to 1985 in Malmö).

- Munthe, Gustaf, Modern hemslöjd, Sv. Slöjdför. Tidskr. 1933. nr. 6.

- Persson, Eric S., Bebyggelsen på Ribershus, Sv. Slöjdf. Tidskr. 1938.

- Thorman, Elisabeth, En textil uppvisning i Malmö, Sv. Slöjdf. Tidskr. 1937. nr. 7.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE