ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

A STUDY OF TEXTILE TRADE

– from 1650s to 1690s

The East India Company (EIC) was founded already in the year 1600 and the Dutch East India Company (VOC) two years later, so long-distance trade – together with national and local commerce – of desired printed cotton and silks etc, was well-established in western Europe in the mid-17th century. This study will give a glimpse of these cloth merchants, drapers, mercers, tailors, sellers of secondhand clothes, and other related occupations that were the foundation for this growing trade. London and the coastal town of Whitby are the focus, together with three artworks of Dutch origin. A few detailed descriptions in Samuel Pepys’ diary related to purchases of fabrics and accessories and my own research of parish church registers, deeds, etc, connected to mercers and tailors in Whitby – are other primary sources included in this study.

This oil on canvas by an unknown artist dated 1690 depicts a prosperous cloth merchant – judging by his clothes – which presents a unique view of the trading of linens or/and woollens as well as the storage of such goods. Two interested clients are considering their purchases of the fabrics for sale, whilst one man helped out with the measuring stick. Surprisingly the fabric was rolled out on the floor, one may have expected a somewhat more careful handling of the valuable textile goods. The painting may be of Dutch origin. (Courtesy of: Museum of London, United Kingdom ID no: 96.120).

This oil on canvas by an unknown artist dated 1690 depicts a prosperous cloth merchant – judging by his clothes – which presents a unique view of the trading of linens or/and woollens as well as the storage of such goods. Two interested clients are considering their purchases of the fabrics for sale, whilst one man helped out with the measuring stick. Surprisingly the fabric was rolled out on the floor, one may have expected a somewhat more careful handling of the valuable textile goods. The painting may be of Dutch origin. (Courtesy of: Museum of London, United Kingdom ID no: 96.120). This detailed depiction from 1670 – ‘In the Draper’s shop’ – by the Flemish painter Adriaen Bloem, gives a contemporary glimpse of the next stage in the trade of fabrics. The cloths are neatly folded on the shelves together with haberdashery goods and possible sample- or account books. The fine fabrics are displayed on the counter for prospective customers who could afford such luxury. (Courtesy of: Hallwyl Museum, Stockholm. Google Art Project).

This detailed depiction from 1670 – ‘In the Draper’s shop’ – by the Flemish painter Adriaen Bloem, gives a contemporary glimpse of the next stage in the trade of fabrics. The cloths are neatly folded on the shelves together with haberdashery goods and possible sample- or account books. The fine fabrics are displayed on the counter for prospective customers who could afford such luxury. (Courtesy of: Hallwyl Museum, Stockholm. Google Art Project). ‘The Tailor’s Workshop’ dating 1661 is chosen to depict the next stage in the trade of cloths. Customers either delivered their newly purchased fabrics to be stitched into various garments, or as the woman in picture, to consult about suitable alterations/mendings on clothing in one’s possession. Both the tailor and his young apprentices are at work on this oil on canvas by the Dutch artist Quirijn van Brekelenkam. (Courtesy of: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Netherlands, No. SK-C-121, Wikimedia Commons).

‘The Tailor’s Workshop’ dating 1661 is chosen to depict the next stage in the trade of cloths. Customers either delivered their newly purchased fabrics to be stitched into various garments, or as the woman in picture, to consult about suitable alterations/mendings on clothing in one’s possession. Both the tailor and his young apprentices are at work on this oil on canvas by the Dutch artist Quirijn van Brekelenkam. (Courtesy of: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Netherlands, No. SK-C-121, Wikimedia Commons).Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) was a naval administrator; he wrote a daily personal diary from 1660 to 1669. This well-known and comprehensive primary source has frequently been used in historical research from all sorts of angles to increase the understanding of London in the 1660s. A few notes of textile interest will demonstrate some of his everyday life experiences on this subject. Furthermore, his father, John Pepys (1601-1680), was a tailor, which may have increased the son’s knowledge of clothes and all sorts of accessories from a young age. On November 11th 1661 for example, the expenses of lace were on his mind:

‘Thence to the Wardrobe to dinner, and there by appointment met my wife, who had by my direction brought some laces for my Lady to choose one for her. And after dinner I went away, and left my wife and ladies together, and all their work was about this lace of hers…So to the Wardrobe, where I found my Lady had agreed upon a lace for my wife of 6l, which I seemed much glad of that it was no more, though in my mind I think it too much, and I pray God keep me so to order myself and my wife’s expenses that no inconvenience in purse or honour follow this my prodigality. So by coach home.’

A few months later, on April 15th in 1662, he both mentioned his work and the desire for fashionable garments:

‘Again at the office in the afternoon to despatch letters and so home, and with my wife, by coach, to the New Exchange, to buy her some things; where we saw some new-fashion pettycoats of sarcenett, with a black broad lace printed round the bottom and before, very handsome, and my wife had a mind to one of them, but we did not then buy one.’

About three years later, on April 4th in 1665, he wrote about purchases of linen cloth, etc:

‘All the morning at the office busy, at noon to the Change, and then went up to the Change to buy a pair of cotton stockings, which I did at the husband’s shop of the most pretty woman there, who did also invite me to buy some linnen of her, and I was glad of the occasion, and bespoke some bands of her, intending to make her my seamstress, she being one of the prettiest and most modest looked women that ever I did see.’

These are just three examples from the extensive diary, but the book The Art of Dress (pp. 110-19) by Jane Ashelford includes a deeper study into Samuel Pepys’ observations of clothes, purchases, everyday life, etc. The two prints below additionally provide some interesting comparisons with the contemporary textile trade in London.

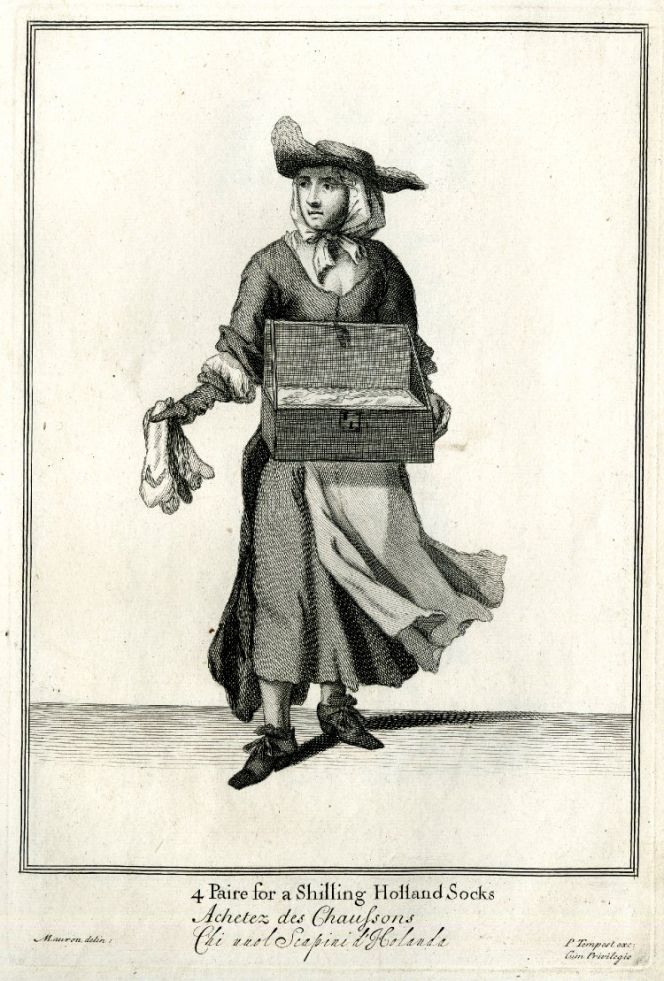

The series of prints showing street traders in London from 1688 include a few individuals with textile connection; an elderly man selling pins, a woman with velvet, satins and other fabrics in her basket and the depicted woman selling “Holland Socks”. This women is one illustrative primary source giving proof for that ready-made garments were for sale in the late 17th century. (Courtesy of British Museum, No: 1972,U.370.4, ‘The Cryes of the City of London Drawne after the Life’).

The series of prints showing street traders in London from 1688 include a few individuals with textile connection; an elderly man selling pins, a woman with velvet, satins and other fabrics in her basket and the depicted woman selling “Holland Socks”. This women is one illustrative primary source giving proof for that ready-made garments were for sale in the late 17th century. (Courtesy of British Museum, No: 1972,U.370.4, ‘The Cryes of the City of London Drawne after the Life’). Whilst this man – from the same series of prints in 1688 – clearly demonstrates the importance of the second-hand clothing market in London. (Courtesy of British Museum, No: 1972,U.370.21, ‘The Cryes of the City of London Drawne after the Life’).

Whilst this man – from the same series of prints in 1688 – clearly demonstrates the importance of the second-hand clothing market in London. (Courtesy of British Museum, No: 1972,U.370.21, ‘The Cryes of the City of London Drawne after the Life’).A comparison with handwritten documents from a small town may be noted from the research on the textile history of Whitby. Still, even if 17th century traditions were outside the period of this work [1700-1914], it was mentioned briefly in the introductory chapter (Hansen…pp. 14-15). Some notes on cloth workers were revealed in this material, in various documents involving deeds, leases, sales, assignments and conveyances together with the parish church registers, which can give us sporadic information about various people and their occupations in Whitby from this time. These sources are evidence for several occupations connected with textiles, whilst the parish church registers for Whitby between 1676 and 1700 seldom mention occupations. One of the exceptions was the trade of tailor/taylor, which was listed continuously between 1686 and 1700, including nine men. Other handwritten documents from the second half of the century reveal a good many more names of tailors. In deeds, during the century, we read of Robert Dobson, Flowergate (1669), Wm. Wigginor at Bridge End (1686-94) and John Graystock (1687-1690s) with his shop and premises at Bridge End. Other occupational categories relating to textiles included ‘mercer’, meaning a businessman who mainly sold fine silk and velvet. Among these, we find mentioned in various documents: Francis Knaggs, Flowergate (1651); Wm. Harrison on the same street (1660-1), Wm. Haslam and John Rymer in Haggersgate (1672-3); and John Hird, Kirkgate (1682). It can be assumed that it was fairly usual to be active in one’s profession for thirty or forty years if one was fortunate enough to live to a good age, but it is not often that we find preserved documents in which the same person is mentioned on various occasions spread over such a long period in the 17th century.

Sources:

- Ashelford, Jane, The Art of Dress – Clothes and Society 1500-1914, London 2002.

- British Museum, Collection Online (Search words: ‘The Cryes of the City of London’).

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015.

- Museum of London (Search words: 'Cloth merchant, 1690').

- The Diary of Samuel Pepys, 1660-1669 (online resource).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE