ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

ALEXANDER POPE

– Textile Observations Linked to the Life of the Famous Poet

The poet Alexander Pope (1688-1744) became one of the most frequently portrayed persons of his generation, which, among other things, provides interesting insight into the functional garments he wore. He was often depicted in meticulous, white, and generously cut linen collarless shirts, comfortable banyans, or plain coats. This essay will also reflect on his long-term poor health, which was influenced by or due to his disability, necessitating his manner of dress, compared to most other pictured contemporary well-to-do men. Notably, his father, who shared his name, had been a wholesale linen merchant who retired from the trade in his 40s, in 1688, when his son was born. Such a textile trader sold large quantities of goods at a low price to shops in London and possibly to drapers and tailors in nearby cities and towns, making it possible for these retailers to increase the cost of linen goods for their customers. A glimpse into his life from a textile perspective may not only be evident from the surprising number of surviving portraits, but also from the fact that engravings of his well-known ‘Pope’s Villa’ at Twickenham, situated along the River Thames, became an inspirational motif for silk-embroidered pictures later in the 18th century.

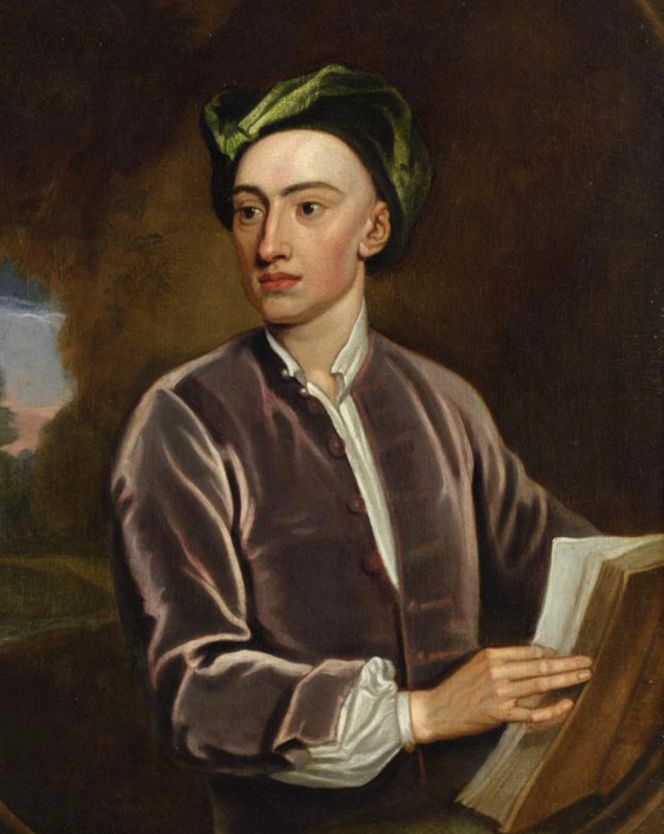

Alexander Pope is portrayed as a hollow-cheeked and philosophical young man, c. 1710-12, resting his elbow on a large leather-bound volume. (Courtesy: St John's College, Cambridge. Art UK. Public Domain).

Alexander Pope is portrayed as a hollow-cheeked and philosophical young man, c. 1710-12, resting his elbow on a large leather-bound volume. (Courtesy: St John's College, Cambridge. Art UK. Public Domain).At a time when he had already been successfully published with ‘Pastorals’, a series of poems about the relationship between nature and art. He is regarded as having been a true believer in friendship, humanity, humbleness and satire – much has been written about his life as a great thinker over the past 300 years, and according to the National Portrait Gallery, he is associated with 46 portraits. A few brief observations here only: in the year 1700, when he was twelve, the family moved from London to Binfield in Windsor Forest. The main reason is believed to be that his parents were Roman Catholics, which gave him restricted access to higher education and even to live within 15 kilometres of central London. It was also around this time that the son became ill in the form of tuberculosis; constant pain stunted his growth, he got a hunchback, and his health became permanently impaired. Over the following five years, he continued mainly with self-studies, the classical writers and poetry from all possible angles; he learned Latin, Greek, French and Italian. In the oil on canvas above, by the Lübeck-born, portrait painter Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723), who had lived in London since the 1670s, Pope is depicted in a soft turban-style velvet cap, a fashionable green silk banyan with red silk lining and a generously cut linen collarless shirt with two unfastened thread shirt buttons. An overall impression is that his colourful clothing stands out from the plain, dark background. A note about his daily routine is worth considering in connection with linen cloth, which is part of Alexander Pope’s entry in a Swedish dictionary printed in 1915. In translation, it reads: ‘He himself was not oblivious to his deformity, but also talked about it with bitter humour. He was so weak that he had to be lifted out of bed, and he could not stand on his legs until he had been swaddled and laced up. This frailty did not hinder him; he was sometimes very active.’ The swaddling or wrapping up of his legs mentioned must have been done with long, shredded pieces of linen cloths, of the finest quality possible, to be comfortable. It is even likely that his father, from his previous linen merchant trade, had kept a large amount of linen for his family’s future use. The imported ‘Holland linen’ may have been preferred as it was regarded as superior.

Portrait of Alexander Pope in his late 20s (circa 1715), painted by the same artist, was visualised as a successful young man with an open book in his hands and an overall healthier outlook with a straight posture. Oil on canvas by the portrait painter Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723). (Courtesy: Unidentified location. Art UK. Public Domain).

Portrait of Alexander Pope in his late 20s (circa 1715), painted by the same artist, was visualised as a successful young man with an open book in his hands and an overall healthier outlook with a straight posture. Oil on canvas by the portrait painter Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723). (Courtesy: Unidentified location. Art UK. Public Domain).Just like in the first visualised portrait, he is not wearing a wig, but instead a soft turban-style velvet cap, here of a grass-green colour. The velvet quality is mirrored in the collarless purple coat, halfway fastened with the cloth-covered buttons of the same shade. The somewhat loose-fitting style is further emphasised because no waistcoat was worn. His plain linen shirt seems to be in the same model as on the portrait a few years earlier: collarless, open with a slit at the front, voluminous sleeves gathered into narrow cuffs. Even if not in the picture, it must be assumed that he wore knee breeches fastened with buttons, whilst the long shirt was tucked in to make it comfortable, and silk stockings reaching over the knee were held in place with knee bands. Around this time, he aspired to have a fine house and garden, but he needed an income to be wealthy enough and financially independent to write poetry. The solution came to be that he made translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey from Greek to English. He took up subscriptions and became his own publisher and bookseller – the monumental project earned him the fortune he needed, and he became a wealthy man. He moved in with his mother in the newly built villa at Twickenham in 1719.

The Thames at Twickenham in 1725 features Alexander Pope’s Palladian-style villa with a light yellow facade spanning three floors and a garden at the riverside. A house that Pope employed the architect James Gibbs (1682-1754) to build prior to Pope taking up residence here in 1719, an area where wealthy families preferred to live in beautiful surroundings, with easy access to central London, just about 15 kilometres on the waterway. Visible in this painting via the row of “palace-like” estates along the waterfront, luxuriant gardens, pleasure boats and a riding couple in fashionable clothing. Many artists depicted this tranquil view of Pope’s villa in the 18th century from various angles. However, most of these paintings were made after his death. It is also noticeable that at least one embroidered picture is extant of his villa (illustrated below), and that the house was completely demolished in 1808 when it was regarded as out of style. | Painting by Peter Tillman (1684-1734). (Courtesy: Twickenham Museum. Public Domain).

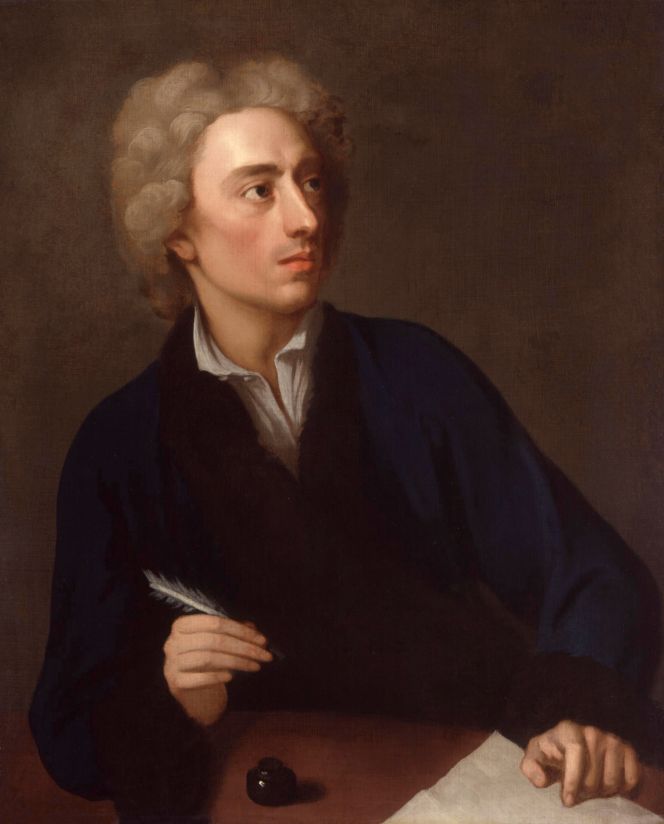

The Thames at Twickenham in 1725 features Alexander Pope’s Palladian-style villa with a light yellow facade spanning three floors and a garden at the riverside. A house that Pope employed the architect James Gibbs (1682-1754) to build prior to Pope taking up residence here in 1719, an area where wealthy families preferred to live in beautiful surroundings, with easy access to central London, just about 15 kilometres on the waterway. Visible in this painting via the row of “palace-like” estates along the waterfront, luxuriant gardens, pleasure boats and a riding couple in fashionable clothing. Many artists depicted this tranquil view of Pope’s villa in the 18th century from various angles. However, most of these paintings were made after his death. It is also noticeable that at least one embroidered picture is extant of his villa (illustrated below), and that the house was completely demolished in 1808 when it was regarded as out of style. | Painting by Peter Tillman (1684-1734). (Courtesy: Twickenham Museum. Public Domain). A creative portrait with an ink bottle, a feather pen and paper of Alexander Pope at almost forty, circa 1727. Oil on canvas by the Swedish portrait painter Michael Dahl (1659–1743), who lived most of his active working life in England. (Courtesy: National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 4132. Public Domain).

A creative portrait with an ink bottle, a feather pen and paper of Alexander Pope at almost forty, circa 1727. Oil on canvas by the Swedish portrait painter Michael Dahl (1659–1743), who lived most of his active working life in England. (Courtesy: National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 4132. Public Domain). Interestingly, above, he was once again depicted in a comfortable, homely banyan-style garment, this time in a dark indigo blue colour, probably made of winter-warm broadcloth, due to the fur edgings at the front and the cuffs. Traditionally, blue had been obtained from woad (Isatis tinctoria) grown in England, but even before 1700, this generally had to compete with imported indigo (several varieties of Indigofera). The desirable dye was imported in the most significant quantities by the British Empire and other seagoing nations of Europe. The Indigofera came from various places in America, the West Indies, India and Africa during the 18th century. This was a valuable source of dye that could be harvested, dried, processed, compressed, and packed in chests for transportation to Europe. One of the colours is highly favoured by the wealthy. Whilst the dramatic lighting in the painting clearly focuses on his facial expression, and in contrast to the two earlier portraits, he now wore a grey wig gathered at the back. The linen shirt has remained almost identical over the fifteen years, featuring a collarless design with two unfastened thread buttons and a slit at the front.

Alexander Pope, at the age of 47-48, around the year 1736. Oil on canvas attributed to the London portrait painter Jonathan Richardson the Elder (1667–1745). (Courtesy: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 24.19. Public Domain).

Alexander Pope, at the age of 47-48, around the year 1736. Oil on canvas attributed to the London portrait painter Jonathan Richardson the Elder (1667–1745). (Courtesy: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 24.19. Public Domain). This portrait of the famous poet contrasts with the previous three in that it is more formal and elegant in both dress and pose. The carefully constructed scene features his white linen shirt – now in a different model – with oversized, voluminous sleeves adorned with ruffles and a straight, long strip of linen fabric at the front. Additionally, he wears a collarless black coat, likely with deep cuffs, and a long waistcoat, paired with matching breeches, white silk stockings, and black shoes with buckles. Visible in the picture is also a longer-styled grey wig compared to about ten years earlier, whilst his hand is clutching a leather-bound volume, which may be one of his own latest works. Just as during most other decades of his adult life, over the last ten-year period (1726-36), he had published poems, as well as various translations and editions of his own letters, at least once a year.

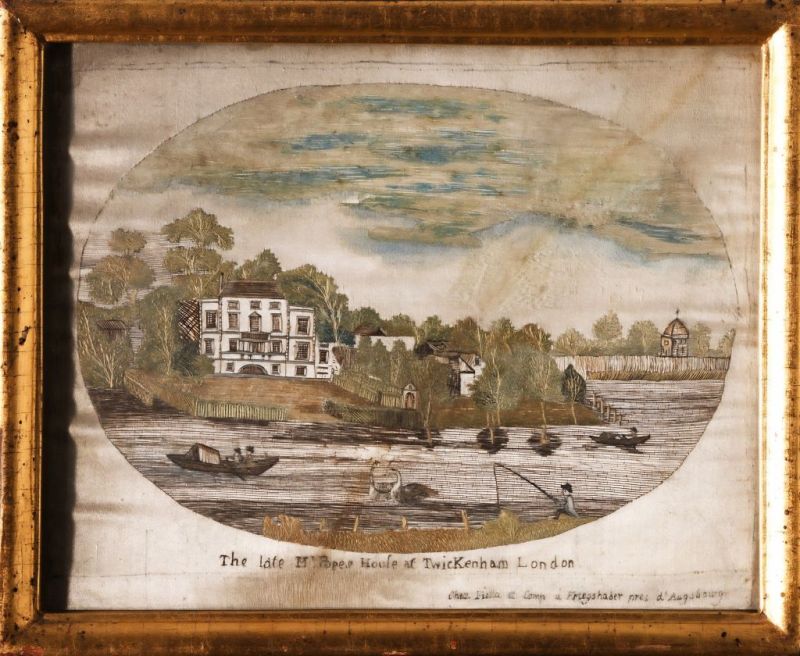

In the 18th century, this type of needlework – known as Georgian Picture Embroideries – reproduced religious scenes, landscapes, or pictures from the theatre or literature, made with silk or fine wool on silk fabric. This extant example is on a white silk ground with several silk stitching techniques, so in the best way possible, it visualises surfaces like floating water, a luxurious garden and architectural details, dating c. 1775-1800. It depicts ‘The late Mr Pope's House at Twickenham, London’, evident in the motif and embroidered title. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0031930. DigitaltMuseum).

In the 18th century, this type of needlework – known as Georgian Picture Embroideries – reproduced religious scenes, landscapes, or pictures from the theatre or literature, made with silk or fine wool on silk fabric. This extant example is on a white silk ground with several silk stitching techniques, so in the best way possible, it visualises surfaces like floating water, a luxurious garden and architectural details, dating c. 1775-1800. It depicts ‘The late Mr Pope's House at Twickenham, London’, evident in the motif and embroidered title. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0031930. DigitaltMuseum).More than half a century after Pope’s death, his house remained associated with the famous poet, and, as mentioned earlier, it was a popular view among many artists. Such a design was usually sketched from a copper engraving; this one, from the engraving firm ‘Chez Fietta et Comp in Kriegshaber’, near Augsburg, was modified to suit the embroiderer’s handicraft. At this time, Augsburg was a creative centre in the southernmost region of the German territories. The scene was probably embroidered by a young woman, unknown in which country, perhaps in Sweden as the picture was part of Norrköpings arbetarförenings museum in the late 19th century (‘arbetarförening’ was a charitable association that assisted low-income families), which may explain why this “old” embroidery (dated to c. 1775-1800), probably was donated by a well-to-do individual to raise funds for the association. The embroidery was then purchased by the Nordic Museum from this association in 1882, where it remains part of their collection. That is to say, Alexander Pope and his former villa have been widely recognised in literary and cultural circles, both within and outside England, for centuries.

Sources:

- Ashelford, Jane, The Art of Dress: Clothes and Society 1500-1914, London 2002.

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015 (Indigo and woad: p. 291).

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textilis Essays. ’A Study of Textile Trade – from 1650s to 1690s’: No: LXV | January 1, 2017.

- National Portrait Gallery (search name: Alexander Pope).

- Nordisk Familjebok, 21st volume, Stockholm 1915 (Pope, Alexander: columns 1372-1375).

- Rogers, Pat, Ed., The Oxford Illustrated History of English Literature, Oxford 1987 (pp. 236-244).

- Rosslyn, Felicity, Alexander Pope: A Literary Life, London 1990.

- Swain, Margaret, Embroidered Georgian Pictures, UK 1994.

- The Nordic Museum (Online Collection: Digital Museum. Information about the ownership of the silk embroidered picture. NM.0031930).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE