ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

DECORATIVE TEXTILES IN HOME INTERIORS

– A Case Study of Embroideries: 1750s to 1900

Appliqué, gold embroidery, drawn thread work, satin-stitch, cross-stitch, petit point, etc. These stitches can be found on domestic furnishings like pictures as well as cushions, upholstered armchairs, mantelpiece cloths and other decorative textiles for the home. The material used might include wool, silk, linen, cotton, gems and beads as well as silver and gold thread. These objects vary enormously in size, from miniature wall pictures to Berlin wool work embroideries a metre high with reproductions of landscapes. The number of colours used also varied greatly as pictures would often be embroidered in every shade of the rainbow or embellished with beads while other embroiderers kept to strict geometrical designs with two contrasting colours. This essay will look closer into Whitby Museum collections aiming to illustrate the traditions of such colourful embroideries over a one-hundred-and-fifty-year-long period.

The first example is the most complex piece of embroidery in the whole collection, which was made during the Victorian period as a mantelpiece decoration. This unique piece is the brilliant work of someone who was able to combine the eye of an artist with exceptional embroidering skills. Her/ his technique involved three applied layers, including a wine-red silk lining, a middle layer of silk to stabilise the pieces of fabric and thirdly the applied patches. The unevenly formed patches are also partly held together by the embroidery itself, which uses back, satin-, chain- and feather stitches. The applied material also uses every type of cloth, including cotton, wool, silk and velvet as well as leather. In addition, there are over a hundred embroidered flowers, medallions, insects, circles and stars etc. The whole work is decorated with beads and pearls ranging from very small to large medallion-shaped pieces. Further ornamentation includes inserted braids of gold and other metal and woven and lace details, as well as hair-work and small metal objects in a variety of shapes, buttons, velvet cords and shells. Finally, the wave-shaped lower edge of this mantelpiece decoration has been completed with blue and red beads. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, EMB 8). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

The first example is the most complex piece of embroidery in the whole collection, which was made during the Victorian period as a mantelpiece decoration. This unique piece is the brilliant work of someone who was able to combine the eye of an artist with exceptional embroidering skills. Her/ his technique involved three applied layers, including a wine-red silk lining, a middle layer of silk to stabilise the pieces of fabric and thirdly the applied patches. The unevenly formed patches are also partly held together by the embroidery itself, which uses back, satin-, chain- and feather stitches. The applied material also uses every type of cloth, including cotton, wool, silk and velvet as well as leather. In addition, there are over a hundred embroidered flowers, medallions, insects, circles and stars etc. The whole work is decorated with beads and pearls ranging from very small to large medallion-shaped pieces. Further ornamentation includes inserted braids of gold and other metal and woven and lace details, as well as hair-work and small metal objects in a variety of shapes, buttons, velvet cords and shells. Finally, the wave-shaped lower edge of this mantelpiece decoration has been completed with blue and red beads. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, EMB 8). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.Many preserved embroideries in Whitby Museum textile and social history collections have been studied from a local as well as a hands-on skill perspective – research which originally was published in my monograph The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914. It must be noted though, that some of these household textiles were presumably made elsewhere in Britain. This essay aims to present additional illustrative material to give further insight into such craft skills made in a domestic sphere, together with thoughts on local, regional, national or even more geographically wide stretching influences for some of these embroideries. Unique personal designs, local traditions, national characteristics as well as mass-produced pattern designs for Berlin wool work etc sold in several countries are part of this museum collection. It is evident that the consumer revolution accelerated during industrialisation by reaching larger groups of society, possibly due to more affordable and increasing amounts of machine-spun yarns, machine-woven canvas and after the 1850s synthetically dyed yarn giving a new often more garish scale of nuances.

Closeup detail of a Berlin wool work with a colourful flower motif against a dark green background in cross-stitch, circa the 1860s-1880s. Notice the strong-coloured purple, greens and mauve which indicate synthetically dyed shades. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, EMB4). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Closeup detail of a Berlin wool work with a colourful flower motif against a dark green background in cross-stitch, circa the 1860s-1880s. Notice the strong-coloured purple, greens and mauve which indicate synthetically dyed shades. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, EMB4). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Another example shows part of an extraordinarily complicated bead embroidery against a wine-red Berlin wool embroidery background. Completed circa the 1860s-1880s, but never mounted or used despite the considerable work that must have gone into it. Beads in matching colours were particularly popular additions to these types of embroideries. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, COS3). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Another example shows part of an extraordinarily complicated bead embroidery against a wine-red Berlin wool embroidery background. Completed circa the 1860s-1880s, but never mounted or used despite the considerable work that must have gone into it. Beads in matching colours were particularly popular additions to these types of embroideries. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, COS3). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.The Berlin wool work embroidery style, dating from the second half of the 19th century, is well-represented on personal items like purses, belts and bags but was also popular for home furnishing objects. This kind of embroidery was sewn on coarse canvas weave with strong wool yarn in tent- or cross-stitch, preferably against a dark foundation with a flower arrangement in many colours. Large or small quantities of beads were frequently included in these embroideries too, as visualised in some of the pictures. The beads would either be used in contrast with the yarn used, or the flowers could be done in beads while the leaves and foundation were embroidered in quality wool. This technique was often used in illustrating flowers, though repeated latticework patterns of stars and squares are also found on minor accessories like purses and bags. Landscapes and religious motifs of this kind were also common – usually in a large format: the collection contains two objects of this kind, one with horses in natural surroundings (95 x 120cm), and the other a Holy Communion scene dated 1881 (56 x 67 cm).

In this closeup, it is visible how the beads had been threaded on a cotton thread one by one, each bead was carefully stitched onto the canvas ground before the next bead was put on the thread and so on. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, COS5). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

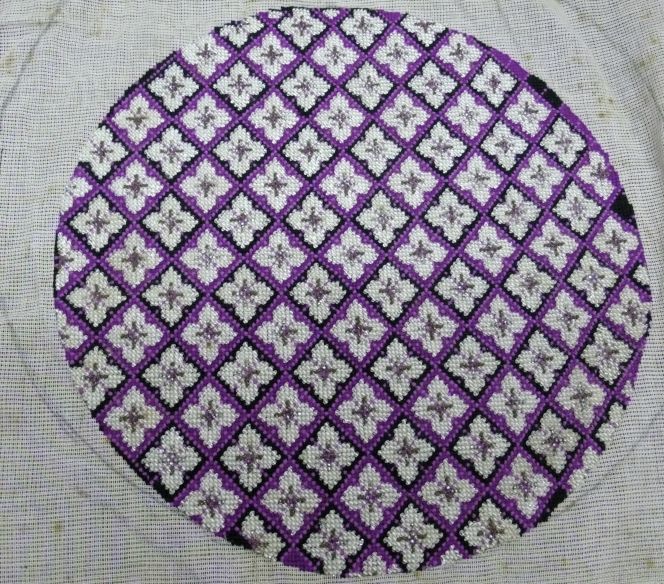

In this closeup, it is visible how the beads had been threaded on a cotton thread one by one, each bead was carefully stitched onto the canvas ground before the next bead was put on the thread and so on. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, COS5). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Another cross-stitch and bead embroidery was done in the 1860s-1880s. The embroiderer has made use of aniline on wool in a variety of shades of mauve and black, using a strictly repetitive design finished with a large number of beads, but it was never mounted. Judging from this category of embroideries in the Whitby Museum collection, the likelihood seems to have increased for the unfinished object to be preserved over time. Maybe, a handicraft piece like this had been put in a drawer to be finished at some other moment in time, which never happened, due to this it is still in perfect condition 150 years later. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, EMB 9). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Another cross-stitch and bead embroidery was done in the 1860s-1880s. The embroiderer has made use of aniline on wool in a variety of shades of mauve and black, using a strictly repetitive design finished with a large number of beads, but it was never mounted. Judging from this category of embroideries in the Whitby Museum collection, the likelihood seems to have increased for the unfinished object to be preserved over time. Maybe, a handicraft piece like this had been put in a drawer to be finished at some other moment in time, which never happened, due to this it is still in perfect condition 150 years later. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Costume Collection, EMB 9). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Engraved design – probably 1860s-1880s – watercolour laid on cloth; image and border 24 cm x 21 cm in size, with colour instructions for the motif on a template squared for copying in embroidery. Notice the multifaceted range of colours, evident in particularly the turquoise and garish greens, which seem to suggest synthetically dyed nuances. This was a German print, but designs stitched with wool on canvas weave were popular with British embroiderers too, as illustrated on several handcrafted pieces above from the Whitby collection. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library no. 34814i. Published in Berlin: Hertz & Wegener: ’A hunter with his dog’).

Engraved design – probably 1860s-1880s – watercolour laid on cloth; image and border 24 cm x 21 cm in size, with colour instructions for the motif on a template squared for copying in embroidery. Notice the multifaceted range of colours, evident in particularly the turquoise and garish greens, which seem to suggest synthetically dyed nuances. This was a German print, but designs stitched with wool on canvas weave were popular with British embroiderers too, as illustrated on several handcrafted pieces above from the Whitby collection. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library no. 34814i. Published in Berlin: Hertz & Wegener: ’A hunter with his dog’).The Berlin wool work craze mainly became so popular in the mid-19th century with the growing number of women who had enough leisure to embroider and adorn their homes with up-to-date interior furnishings and the increasing availability. Such embroidery was comparatively easy for amateurs since the instructions came with a visual pattern on charted paper that showed how the stitches in each colour should be counted and sewn with wool yarn on a coarse canvas. This kind of embroidery had been marketed as early as the 1830s, but the Great Exhibition of 1851 and the introduction of women’s magazines with their special housekeeping tips and interior-decoration novelties contributed to greatly increasing its popularity. An ability to embroider beautifully was also considered a particularly suitable accomplishment for girls in well-off families and their mothers, like piano playing, watercolour painting and reading. Besides, it was a mark of the family’s high social status if the women could afford to occupy themselves with “dainty embroidery” as a recreation, rather than need to undertake paid work to contribute to the family’s finance. On the other hand embroidery and sewing at home were considered a suitable source of income for women from the higher classes, if the family happened to be temporarily or for longer periods short of money.

This final illustration has similarities with the wool and bead embroideries above as a decorative late 19th century interior furnishing detail in cross-stitch, a small-sized embroidery that was simple to execute, but instead the more expensive silk material was used. The thread for the embroidery is silk, as is the braided strap in matching colours, while the back of the embroidery has been lined with blue silk cloth. It was once part of a curtain arrangement. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History Collection, SOH561). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

This final illustration has similarities with the wool and bead embroideries above as a decorative late 19th century interior furnishing detail in cross-stitch, a small-sized embroidery that was simple to execute, but instead the more expensive silk material was used. The thread for the embroidery is silk, as is the braided strap in matching colours, while the back of the embroidery has been lined with blue silk cloth. It was once part of a curtain arrangement. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History Collection, SOH561). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.An older type of embroidery mostly dating from the second half of the 18th century is known as Georgian Picture Embroideries. These might reproduce religious scenes or pictures from the theatre or literature made with silk or fine wool on silk cloth. There are two embroideries of this kind in the Whitby collection. Both religious characters, feature ‘Isaac at the Well’ and the ‘Sacrifice of Isaac’, and were probably produced at the end of the 18th century or a little later. Both have painted hands and feet, with other details sewn in long and short satin stitches with added French knots. This extremely fine detailed work must have been done by an accomplished embroiderer, on a fine silk base, which has now partly decayed while the actual embroidery is still in good condition. It is by no means unusual for old silk to “eat itself up” through wear and tear, or from weight when a garment has been kept hung up, or when the act of embroidering itself has caused the cloth to disintegrate. In another extant piece, parts of the embroidery itself are in the process of disintegrating, since the wool yarn used has been made brittle by a powerful mauve colour that became popular after the introduction of aniline dye in 1856. According to the catalogue card, this particular piece of embroidery was done by Mrs Clarkson in Whitby, on canvas with mainly wool yarn but also with silk in cross-stitch and petit point.

An embroidery dated 1797 features a picture of Whitby Abbey sewn entirely on silk in backstitch with black silk thread. This kind of embroidered reproduction of the engraved or copperplate illustration of a well-known local building was popular around the turn of the century in 1800. It is in general embroideries from well-to-do households that have mostly had the good fortune to be preserved for future generations. This is because those living when the object was made were as likely as succeeding generations to want to preserve exclusive accessories, while humble everyday items from working-class homes would be more likely to be consumed until worn out, altered, adapted, or re-used as rags.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015. (pp. 313-327. For full Bibliography and a complete list of notes, see this book).

- Polkinghorne, R.K. & M.I.R., The Art of Needlecraft, London.

- Swain, Margaret, Embroidered Georgian Pictures, UK 1994.

- Whitby Gazette, 1855-1914 (Whitby Museum, Library & Archive).

- Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, & Photographic Collection (Whitby Lit. & Phil.).

- Whitby Museum, Costume and Textile Collection (Whitby Lit. & Phil.), UK. [In-depth research (in the years 2007-11) of the entire collection connected to embroideries and sewing].

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE