ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

DOUBLE INTERLOCKED TAPESTRIES

– Materials and Dyes

The double interlocked tapestries, or “rölakan” – along with many other textiles – only begin to achieve their beauty, strength, and usability when the details of preparation, weaving, and post-production all come together. During the preparation of weaving "rölakan” in the 18th and 19th centuries, each element was crafted by hand with the aid of various simple tools. Thus, it was of utmost importance to be meticulous in choosing materials, natural dyes, pattern composition, markings with names or letters, the cushion’s filling, as well as any decorative borders, ribbons, or corner tassels.

Tools for wool preparation with hand carders and a so called ‘scrub-stool’. (Owner: Bjärnum hembygdsförening). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Tools for wool preparation with hand carders and a so called ‘scrub-stool’. (Owner: Bjärnum hembygdsförening). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.It is important to emphasise that the patterns and natural dyes chosen by the Swedish woman weavers were not random or down to her personal preference but stemmed from historical traditions, local characteristics and the economic conditions of said time. However, this did not prevent the development of personal colour/pattern choices in conjunction with the choice of decorative ribbons, tassels, borders or markings, which gave a unique touch to each weave. Even with studying nearly 2,000 double-interlocked tapestries alone for this project, no two were identical.

Unspun flax, which needed to be spun and twinned before it was strong enough for a warp thread. (Private ownership). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Unspun flax, which needed to be spun and twinned before it was strong enough for a warp thread. (Private ownership). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.Nearly all (c. 95%) of the documented double interlocked tapestries or “rölakan” have flax for the warp and wool for the weft. The other examples have hemp as a warp thread, yet it is sometimes uncertain if flax or hemp had been used, whilst in some individual cases, jute or cotton may have been used. With the weft, the wool was on some rare occasions, added with metal thread, used to strengthen the vividness of the woollen yarns. Whilst in poorer regions; a stronger cow hair yarn could be mixed with the wool to increase the amount of raw material.

All colours of the spectrum were produced from natural dyes. Primarily from plants but also in some aspects from various lice, first and foremost the cochineal from the second half of this period.

Dyer’s weed (Reseda Luteola). One of the best and hardiest plants which were used in the dyeing of yellow shades. (Lindman, C.A.M., Nordens Flora, 1917-1926).

Dyer’s weed (Reseda Luteola). One of the best and hardiest plants which were used in the dyeing of yellow shades. (Lindman, C.A.M., Nordens Flora, 1917-1926).Generally, these textiles were woven in clear, sharp and saturated colours, often with great contrasts. Yellow and brown tones were the easiest to produce when using readily available Nordic flora. Whilst green, red and blue carried certain limitations, these colours were preferred in regions of economic prosperity, where it was possible to spend a lot of time on weaving and dyeing or buying imported dyes.

Here it is clearly shown how the yellow colour has faded on a cushion from Gärds or Villands districts in Skåne, Sweden. (Owner: Helsingborg Museum). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Here it is clearly shown how the yellow colour has faded on a cushion from Gärds or Villands districts in Skåne, Sweden. (Owner: Helsingborg Museum). Photo: The IK Foundation, London. Detail of a border from the same “rölakan” cushion, shows us how finely woven the motifs could become, when the flax warp is covered by the woollen yarn of a fine quality, together with a suitable reed density. (Owner: Helsingborg Museum). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

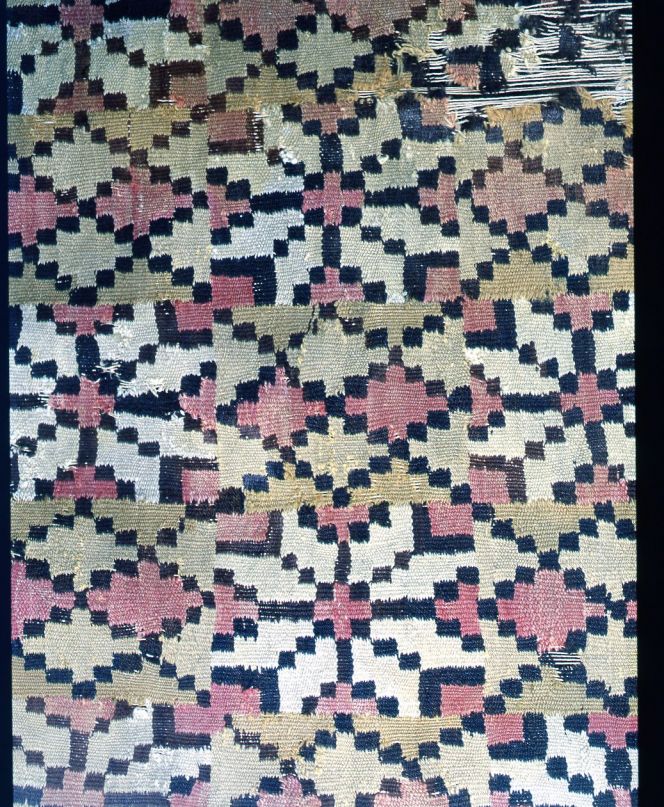

Detail of a border from the same “rölakan” cushion, shows us how finely woven the motifs could become, when the flax warp is covered by the woollen yarn of a fine quality, together with a suitable reed density. (Owner: Helsingborg Museum). Photo: The IK Foundation, London. In contrast to the double interlocked tapestry with a simple star motif, where both the warp thread and woollen weft are of significantly coarser quality. Skåne, Sweden. (Owner: Malmö Museum). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

In contrast to the double interlocked tapestry with a simple star motif, where both the warp thread and woollen weft are of significantly coarser quality. Skåne, Sweden. (Owner: Malmö Museum). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Textila Kuber och Blixtar – Rölakanets Konst- och Kulturhistoria, Christinehof 1992 (pp. 41-57).

- Hansen, Viveka, Swedish Textile Art, London 1996.

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE