ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

EDUCATION AND CLOTHING

– The Swedish Aristocracy in Colmar: 1785 to 1788

Timetables, reports, marks, receipts, listing of clothes, correspondence and other contemporary 1780s documents will form this second essay about the three Piper brothers – Carl Claes (1770-1850), Gustaf (1771-1857) and Eric (1772-1833). At this moment in time they had arrived after a 26-day journey from southernmost Sweden to École militaire de Colmar, accompanied by Andreas Norberg along with two servants and two other Swedish youngsters. A school where these young aristocrats came to stay from autumn in 1785 to spring 1788. Due to the rare selection of extant primary sources, it is possible to get a unique insight into their daily lives as well as the educational aims of such an elite school in France.

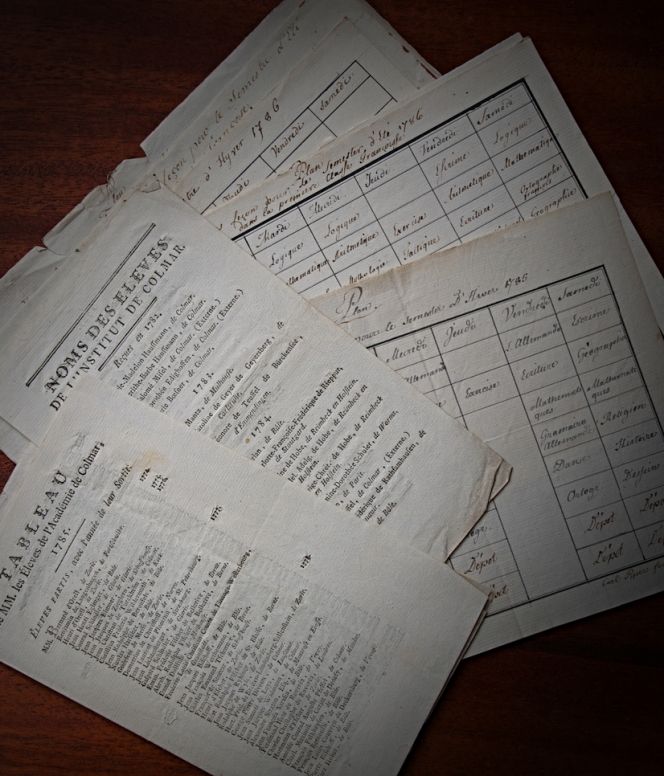

Well-preserved documents dating from 1785 and 1786 – including listed pupils in previous years and the Piper brothers’ time tables. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof…no E/III). Photo: The IK Foundation.

Well-preserved documents dating from 1785 and 1786 – including listed pupils in previous years and the Piper brothers’ time tables. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof…no E/III). Photo: The IK Foundation.Five days after arriving at Colmar, the companion Andreas Norberg wrote a letter on 18th September in 1785 to the father, Carl Gustaf Piper, which gave information about practical matters and his view of the school. He noted: ‘The inspectors and teachers, all are wise, sensible and intelligent persons’. The three sons had by now also received their uniforms so they could be formally enrolled in the education during a ceremony of ‘song, music and embracing’. Norberg’s final letter regarding the school to the father in Stockholm was sent when he had returned back home to the Swedish manor house Krageholm on 26th October. By now, his views were not entirely positive, as he regarded the two oldest sons as too experienced compared to the level of ‘imperfect education’, particularly in French and Latin. However, when it came to the moral and behavioural rules on the school, he was enthusiastic: ‘Day and night they stand under continuous and secure supervision. Their health is improved by physical exercises and they learn to live together with a mix of people, due to that the number is no less than 49’.

Evidenced by lists of pupils in extant such documents, the majority of the enrolled came from a reasonably close-by geographical area within a radius of 200 kilometres – ‘Zurich, Strasbourg, Berne, Lausanne, Karlsruhe, Belfort’. But students also came much longer distances, including: ‘Danemarc, Londres, St Petersbourg, New-Jersey en Amérique, Moscue and Stockholm’. The school was either named l’Académie de Colmar or Ecole militaire de Colmar, furthermore part of the establishment was reserved for girls and named l’Institut de Colmar.

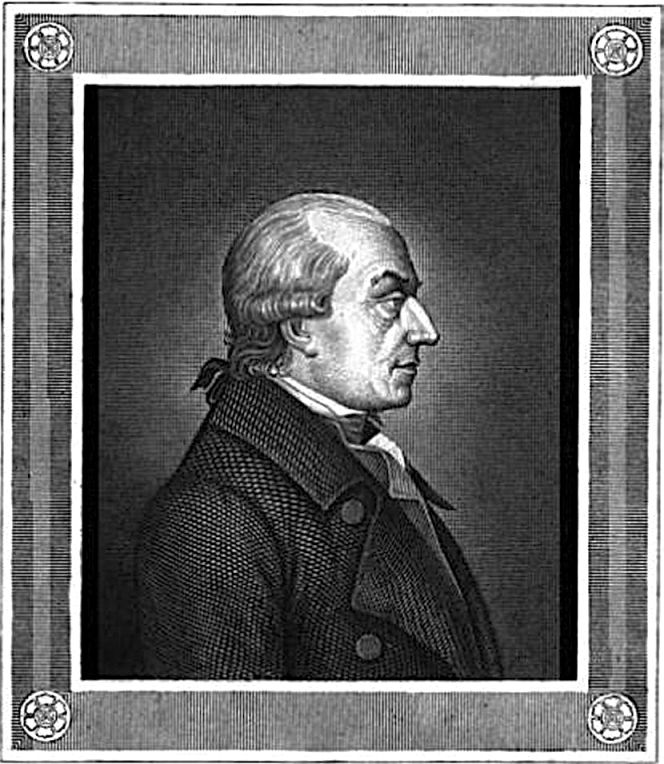

This portrait of the poet Gottlieb Konrad Pfeffel (1736-1809), probably depicted him in the 1770s or 1780s, after he had opened the school in Colmar 1773, primarily aiming to get the sons of aristocratic Protestants of Europe enrolled. In letters from Andreas Norberg to the boys’ father, Carl Gustaf Piper, Pfeffel and his academy were also mentioned in the terms of ‘Pfeffel’s establishment’. (Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain).

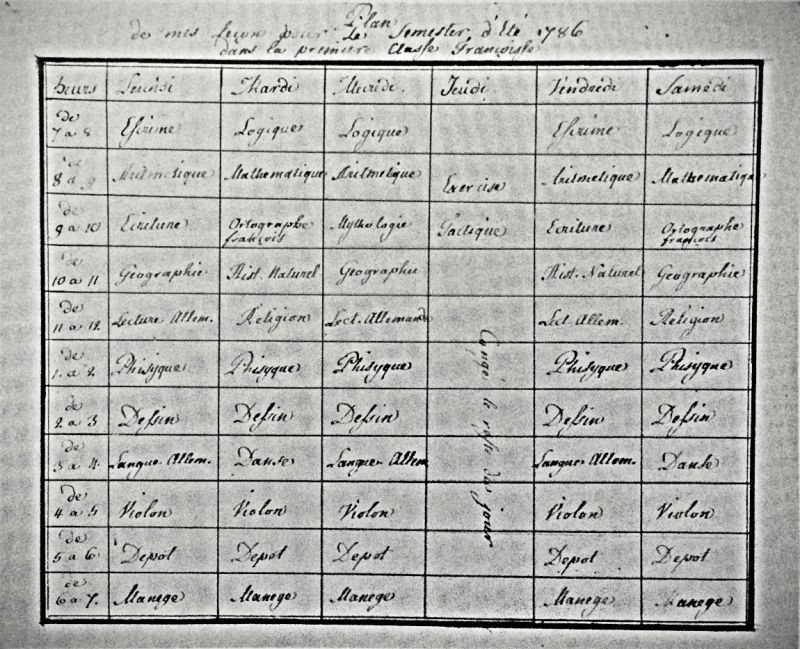

This portrait of the poet Gottlieb Konrad Pfeffel (1736-1809), probably depicted him in the 1770s or 1780s, after he had opened the school in Colmar 1773, primarily aiming to get the sons of aristocratic Protestants of Europe enrolled. In letters from Andreas Norberg to the boys’ father, Carl Gustaf Piper, Pfeffel and his academy were also mentioned in the terms of ‘Pfeffel’s establishment’. (Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain).  Weekly timetable from Monday to Saturday, for the first French class in summer term of 1786. Judging by the extant timetables and reports, the main language for the three Piper brothers was French, whilst some students who enrolled at the school, probably had German as their main language. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof…no E/III). Photo: The IK Foundation.

Weekly timetable from Monday to Saturday, for the first French class in summer term of 1786. Judging by the extant timetables and reports, the main language for the three Piper brothers was French, whilst some students who enrolled at the school, probably had German as their main language. (Collection: Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof…no E/III). Photo: The IK Foundation.The six-day school week started at 7.00 or 8.00 am and continued up to 7.00 pm, including 11 to 12 lessons every day, except for Thursday, which only had two lessons. A multitude of subjects was divided into four main areas, and these are listed here to give an idea of the multifaceted education taking place with some variation over the years 1785 to 1788.

- Science: natural history, religion, arithmetic, algebra, geometry, architecture, logic, law and physics.

- History and Language: history, geography, mythology, statistic studies, heraldry, literature, French, German, Latin, Italian and English.

- Arts: writing in French and German, drawing, playing musical instruments, dancing, fencing, riding, and weaponry.

- Physical exercise and Amusements: military exercise, manège, games, amusements, plays, balls, travel, walking, visits and personal relations with teachers and students.

This somewhat earlier 18th century engraving of ‘Fencing: two men are practising their positions’ is an interesting comparison to the Piper brothers. Whilst fencing was practised during two hours in the weekly curriculum in 1785 and continued to be included as a subject over their study years. It may also be noted that the depicted young men of wealth wore uniform-like garments, just as the Colmar military school had a school uniform style dress code, judging by extant correspondence and lists of clothing. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library no. 34630i, originally published in February 1763).

This somewhat earlier 18th century engraving of ‘Fencing: two men are practising their positions’ is an interesting comparison to the Piper brothers. Whilst fencing was practised during two hours in the weekly curriculum in 1785 and continued to be included as a subject over their study years. It may also be noted that the depicted young men of wealth wore uniform-like garments, just as the Colmar military school had a school uniform style dress code, judging by extant correspondence and lists of clothing. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library no. 34630i, originally published in February 1763). The grading of each and every student’s effort included not only all subjects listed above but also physique et moeurs, which seems to have been seen as of great importance. These personal characters were judged from four main aspects. Firstly, it covered health, body size, intelligence, goodness, behaviour, manners and ways of living. The second view of looking at the individual student included braveness, virtues, godliness, how one regarded oneself, how his superior judged his character, how much liked he was among friends and finally the behaviour towards his servants. The third group was closely connected to the second, but all involved were looking for possible negative reasons for the student. The fourth and last group judged distinctions and marks of honours, leadership, diligence, advancement, promotions, and prizes. Even from a 1780s perspective, such in-depth judgements of each and everyone’s personality could easily have become fortuitous and unfair.

From a close study of the extant documents, the Piper brothers received their grades three times a year – in January, April, and October – in all subjects they attended and for physique et moeurs, as described above. Furthermore, a written statement addressed to the father, Carl Gustaf Piper, in Stockholm included notes about general behaviour and diligence during lessons and spare time alike. In this aspect, the brothers were seen as very good, good or rather good. It may be assumed that all three followed the same curriculum, as one timetable was only preserved for each term.

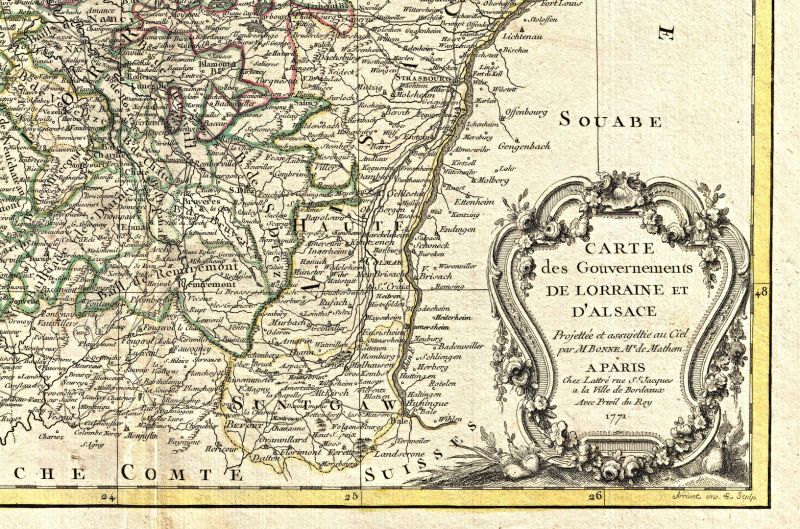

Part of a map dated 1771, including Colmar in France, situated west of the River Rhine and close to the German speaking area of Baden. | ‘Rigobert Bonne’s decorative map of the French winemaking regions of Alsace and Lorraine’. (Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain).

Part of a map dated 1771, including Colmar in France, situated west of the River Rhine and close to the German speaking area of Baden. | ‘Rigobert Bonne’s decorative map of the French winemaking regions of Alsace and Lorraine’. (Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain).From the timetables, it can be revealed that walking and shorter journeys took place as part of education, but where they went is unknown. However, Colmar is situated between the low-altitude mountainous area of Vosges in the west and the River Rhine to the east, so there must have been plenty of opportunities for walking, riding tours on horseback and sailing by river boats alike. Just like the travel with a horse and carriage by the main road through the town was leading to Strasbourg, Mulhausen and other places. The extant list of clothing and accessories gives further interesting details about the boys’ daily life. For the night, they used nightshirts and nightcaps, ‘3 pairs of linen sheets’ for the beds and ‘3 dozen hand towels’ were also included. Regarding the students’ clothes, it is known via contemporary correspondence that some type of school uniforms – or more of a dress code – were in use. Judging by this list, these garments were blue, green and white in colour:

- 3 blue dress-coat tails

- 3 pairs of green breeches

- 6 pairs of white waistcoats

- 3 surtouts

- 3 pairs of shoes and knee-buckles of silver

- 3 neckcloths-clasps

- 3 pairs of galoshes

- 9 neckcloths

- 3 dozen handkerchiefs

- 3 pairs of white silk stockings

Additionally, in the young Piper brothers’ possessions were one pocket watch with gold chain each as well as a number of breeches, linen shirts, socks etc. The list also reveals that wigs were in use due to that it included: ‘3 powder shirts and 2 powder pouches’. Whilst an undated note for future purchases by Les Comtes des Piper recorded necessary items as shirts and linen sheets, but also accessories as 6 combs and 3 broshes d’habits.

It must be taken into account that the young boys Carl Claes, Gustaf and Eric predominately had lived during their childhood in Stockholm in one of the wealthiest aristocratic families closely connected to the Royals. Their father, Carl Gustaf Piper at this time, was the tenant in tail of the Piper family as owners of several manor houses in Sweden, a Count and upper chamberlain since 1777 for Gustaf III’s consort Queen Sophia Magdalena. The boys' childhood years must have been the most privileged, highly inspired by the then King’s admiration for everything French – art, theatrical plays, fashion and language. To let the sons study at École militaire de Colmar must have been regarded as a suitable choice during the mid-1780s for future success in life.

Original documents were written in Swedish and French. All quotes in this essay have been translated to English. This is the second and final essay about the Piper brothers' educational years in Colmar.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Pojkarna Pipers utlandsstudier’, Österlen, pp. 5-14. 1999 [pp. 9-13].

- Hansen, Viveka, Katalog över Högestads & Christinehofs Fideikommiss, Historiska Arkiv, Piperska Handlingar No. 3, London & Christinehof 2016.

- Historical Archive of Högestad and Christinehof, Sweden (Piper Family Archive, no E/III: including, 1. Letters 1785-88. 2. Account book in 1785. 3. Miscellaneous documents. 4. Reports and Marks for the students 1785-88 & G/V 2: Receipts etc connected to the Colmar journey).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE