ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

HEALTH, ILLNESS AND DEATH

– Textile Observations by 18th century Travelling Naturalists

This essay aims to look closer at ill health and traditions around the end of life in the context of clothing and various textiles – studied via travel journals and correspondence by Carl Linnaeus’ seventeen Apostles. Young men who made natural history journeys to more than 50 countries over the period 1745 to 1799. The method by which the most suitable candidates were selected for these adventurous tasks was of crucial importance, due to that the travellers’ practical and theoretical knowledge had to be weighed against experience, enthusiasm and suitability. Despite careful preparations, nearly half of them sadly died, either during the voyage or soon after as a consequence. However, it was not only from a personal perspective they made notes about poor health or severe illness and the importance of textiles; other observations regarded the demise of travel companions, about a local individual’s death, funerals, mourning or ceremonial commemorations in visited countries.

![All of the seventeen apostles, excepting Johan Peter Falck (1732-1774), traversed the often perilous waters of the North Sea. This image from the Swedish East India Company captain Carl Gustaf Ekeberg’s (1716-1784) travel journal, embarked upon in 1770, does express the hazards to the ships even on a minor sea such as the North Sea [Nordsiön]. Seven of the apostles passed away during their long voyages to all continents, but none of them died due to drowning or shipwrecking. (From: Ekeberg…1773).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/1-ekeberg-1771-664x619.jpg) All of the seventeen apostles, excepting Johan Peter Falck (1732-1774), traversed the often perilous waters of the North Sea. This image from the Swedish East India Company captain Carl Gustaf Ekeberg’s (1716-1784) travel journal, embarked upon in 1770, does express the hazards to the ships even on a minor sea such as the North Sea [Nordsiön]. Seven of the apostles passed away during their long voyages to all continents, but none of them died due to drowning or shipwrecking. (From: Ekeberg…1773).

All of the seventeen apostles, excepting Johan Peter Falck (1732-1774), traversed the often perilous waters of the North Sea. This image from the Swedish East India Company captain Carl Gustaf Ekeberg’s (1716-1784) travel journal, embarked upon in 1770, does express the hazards to the ships even on a minor sea such as the North Sea [Nordsiön]. Seven of the apostles passed away during their long voyages to all continents, but none of them died due to drowning or shipwrecking. (From: Ekeberg…1773).Several of these naturalists were trained physicians within their education, whilst a few worked on board East India Company ships as surgeons where poor health and, at times, frequent deaths were a reality throughout the long sea voyages. Illnesses mentioned in correspondence, physician journals and diaries alike were consumption, falling sickness, the shivers, German measles, dysentery, gangrene, scurvy etc. Various sorts of linen, cotton and woollen cloths could assist in the healing of the patients. Even so, many times illnesses were contracted where no cures were known. To mention two of Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) former students who died at a young age; Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752), doctor of medicine, died at the age of 30, in a village close to Smyrna (today Izmir) of consumption [tuberculosis], a very common disease as he had been infected with already before leaving Sweden. Whilst Pehr Löfling (1729-1756), a few years later, died in a mission in Guyana, Venezuela, of a ‘fever’ at the age of 27. Exactly what sort of fever is unknown, but the most common ailment in hot climates was either malaria, yellow fever or dysentery.

The ship’s physician or barber-surgeon was an extremely important person onboard the ships bound for East India. The voyage usually lasted one and a half to two years, but this one, as studied via Carl Fredrik Adler’s (1720-1761) medical journal, took more than three years. Alongside the sail makers and the carpenters, the doctor onboard was regarded as part of the category of especially essential and useful individuals. To aid him in his task, he had his medicine chest containing medicines, instruments and other crucial items for examinations and treatments. The crew, supported by orders from the higher-ranking officers, could also do a great deal themselves to keep illnesses at bay. Cleanliness was regarded as of primary importance, and for that reason, the ship should be properly swabbed inside out every day. Airing the bedding, attacking vermin at an early stage to stop it from spreading to the entire crew and keeping clothes free from humidity could also contribute to keeping those onboard in better health. For Adler, as a physician onboard such a Swedish East India Company ship, clean fabrics were vitally important, his notes revealing how cleanliness benefited the sick, how dampness and dirt ought to be kept to a minimum, and how necessary access to fresh water onboard was for washing. Although the methods of a ship’s physician in the mid-1700s failed on many points, seen through modern eyes, studies of Adler’s patient records show that his knowledge of the value of cleanliness was of great benefit to the patients. This was his second voyage of four – lasting from 1753 to 1756 – on the last one, he died on the outward leg in 1761 off the coast of Java, or even earlier during the passage by an unknown illness.

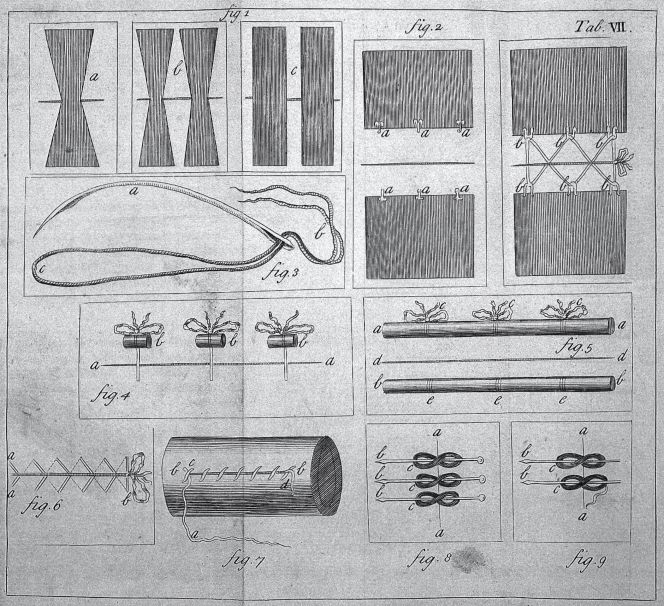

Even if ill health in general seems to have been the most common ailment onboard the East India company ships, judging by Adler’s medical journal, but the ship’s physician on a merchant ship nonetheless had to know about surgical procedures, primarily amputations. This illustration from a contemporary publication on the subject, entitled The elements of surgery...Adapted to the use of the camp and navy... by Samuel Mihles 1764, demonstrates different stitching methods carried out with a sturdy bent needle. Figure 3 was described as follows: ‘A large crooked needle, with a double thread, to make the quilled and other sutures in large wounds. a. the needle arched, b. the double thread, c. the bow end of the thread.’ What is not mentioned in this publication, however, is whether thread of linen, cotton or silk was preferred for the sutures, but all the materials were probably in use in the mid-1700s. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Trust, L0029963, Table C & quote p. 288).

Even if ill health in general seems to have been the most common ailment onboard the East India company ships, judging by Adler’s medical journal, but the ship’s physician on a merchant ship nonetheless had to know about surgical procedures, primarily amputations. This illustration from a contemporary publication on the subject, entitled The elements of surgery...Adapted to the use of the camp and navy... by Samuel Mihles 1764, demonstrates different stitching methods carried out with a sturdy bent needle. Figure 3 was described as follows: ‘A large crooked needle, with a double thread, to make the quilled and other sutures in large wounds. a. the needle arched, b. the double thread, c. the bow end of the thread.’ What is not mentioned in this publication, however, is whether thread of linen, cotton or silk was preferred for the sutures, but all the materials were probably in use in the mid-1700s. (Courtesy of: Wellcome Trust, L0029963, Table C & quote p. 288).  This piece of linen/cotton fabric was once part of Anders Berch’s (1711-1774) educational collection – contemporary in time with the travelling naturalists. A tabby woven Swedish quality, with a linen warp and cotton weft, which may exemplify a type of cloth useful when caring for patients onboard. Even if pure linen cloths probably was most common to use. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0017648B.108A. Digitalt Museum).

This piece of linen/cotton fabric was once part of Anders Berch’s (1711-1774) educational collection – contemporary in time with the travelling naturalists. A tabby woven Swedish quality, with a linen warp and cotton weft, which may exemplify a type of cloth useful when caring for patients onboard. Even if pure linen cloths probably was most common to use. (Courtesy of: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0017648B.108A. Digitalt Museum).The apostle Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805), who also travelled on a Swedish East India Company ship but as a ship’s chaplain-cum-naturalist had the fortune to return back in reasonable good health and reached the old age of 82. But during his time in the Canton area [today Guangzhou], he noticed local traditions linked to clothing, funerals and commemoration in September and October 1751.

- ‘Rich people build pagodas sometimes, that their relations may be every day employed in burning incense, sacrificing, and other ceremonies, in commemoration of their saint. The priests are called Vau-siong by the Chinese, and Bonzes by the Europeans. They go with their heads bare and shaved, dress in steel-coloured silk coats with wide sleeves, which look like surplices, and wear rosaries about their necks. When they officiated on the festival of the lanterns, they had red coats and high caps.’

- ‘A good way out of town, on the right of the high road, I arrived at the European burying-place, which was on a hill without any sense, or distinction from the other hills. The inscriptions on the tombstones are not all legible, on account of the rubbish lying on them: however, I could see that Swedish captains and supercargoes had died in this country. The corpse which was now to be buried was carried by six Dutch grenadiers. The procession followed in Palankins without order. The Chinese merchants who were here present, mourned with white, long, cotton handkerchiefs, which were tied as the ribbons of an order, over their common clothes.’

The Linnaeus’ apostle, Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1728), travelled about two decades later with a Dutch East India Company ship towards the Cape. To prevent ill health from spreading, the crew were expected to stay on deck as often as possible, chests and hammocks to be aired, and everybody to keep both themselves and their clothes clean. One big problem, as Thunberg saw it, was that many were poorly equipped with clothes, something that made their recovery harder. Nevertheless, another perspective arose when someone passed away, as Thunberg mentioned in his journal on 26 March in 1772: ‘When the surgeon has made his report of the death of any person, the mate of the watch immediately orders his chest to be brought upon deck, and distributes his clothes among those who have occasion for them.’ Furthermore, when, after nearly three months at sea, the captain finally began to hand out more necessary garments, the journal notes two days later: ‘The Company sends out stockings likewise and clothes made of coarse and thin cloth, which are delivered out upon credit to such as choose to avail themselves of this privilege; this distribution is made at the captain’s pleasure, to those whom he favours, and not always where it is wanted.’ There were in other words men who still lacked sufficient clothing, but two days later they too received their rations. ‘Clothes were now, for the second time, distributed among such of the soldiers as had hitherto been half-naked.’ It has to be mentioned that the distribution was done neither out of charity nor consideration; those garments were to be paid back through work during the voyage. Thunberg was undoubtedly relieved to be leaving the ship at the Cape, having established that 115 men had died during the stop-over at Texel and the sea voyage to the Cape. It was also noted, however, that there were Dutch ships where the mortality was even greater.

The contemporary apostle Anders Sparrman (1748-1720), who also stayed in the Cape area for natural history observations, additionally had the opportunity to be an assistant botanist on James Cook’s (1728-1779) second voyage. On 14 September 1773 – while sailing in the waters of the Society Islands – his journal included notes about the importance of bark clothes for the local inhabitants’ funeral and mourning traditions as he saw it from his European perspective:

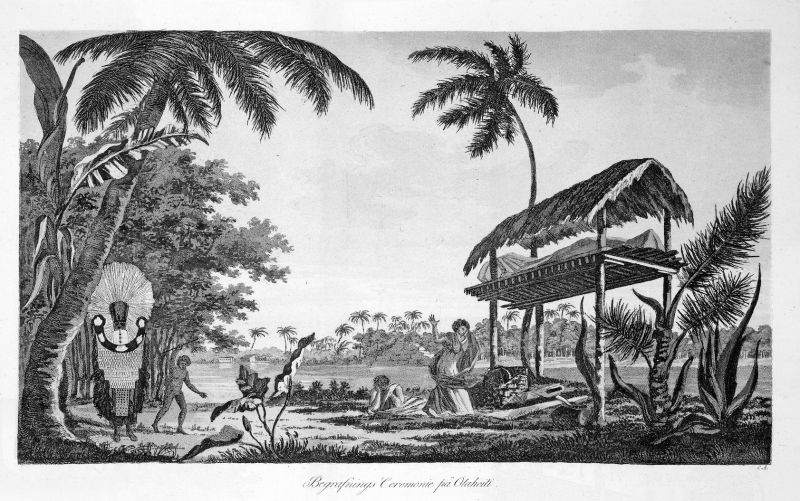

- ‘Just as we arrived on Otaha, a so-called hiva, dance or performance was arranged in honour or memory of someone deceased, for on the same occasion, we saw at some distance a woman, her body and face blackened and dressed in the curious customary mourning dress. While the hiva was going on the considerable crowd of people then made space for the deceased’s mourning relatives of all ages to appear by the entrance in pairs in many lines, naked and shining with the coconut oil with which they had oiled themselves, red girdles round their middles and large plaits of black false hair around their heads. These are called tamu, and at first plaited from human hair into narrow strips like fishing- lines which are then held together in bigger bunches. The same procession of mourning relatives appeared once more in the said manner towards the end of the hiva, when a bolt of the local cloth was spread out in front of them, after which the same cloth was handed over to their drummers and musicians, the actors probably getting their share of it too. Even on these islands the deceased and their heirs thus seem to be subjected to embarrassing ceremonies and expenses.’

During a visit on Tahiti in the previous month (August 1773) the bark cloth was also noticed to be of ceremonial significance in Sparrman’s journal. The travellers became spectators at a dance, regarded as honouring dead relatives, where the dancers wore bark cloths dyed red in the shape of girdles around the waist. Back again on a second visit to Tahiti in 1774, a mourning outfit was described, called Tupapao, which at the bottom resembled an apron ‘studded with round polished buttons of coconut shell’. The garment was regarded as very valuable for bringing back to Europe as, ‘after Capt. Cook’s return home, it fetched 25 Guineas’. Interestingly, Sparrman’s journal from Society Islands (September 1773) also included a reflection on how inappropriate it was regarded for a European man to show sadness and cry, due to that ‘our civilised upbringing frequently demands us to control the most beautiful indication of emotions as being inimical to decent manliness.’ (This illustration was initially published in Anders Sparrman’s Swedish original edition of 1802 and the plate was named ‘Burial Ceremony on Otaheiti’).

During a visit on Tahiti in the previous month (August 1773) the bark cloth was also noticed to be of ceremonial significance in Sparrman’s journal. The travellers became spectators at a dance, regarded as honouring dead relatives, where the dancers wore bark cloths dyed red in the shape of girdles around the waist. Back again on a second visit to Tahiti in 1774, a mourning outfit was described, called Tupapao, which at the bottom resembled an apron ‘studded with round polished buttons of coconut shell’. The garment was regarded as very valuable for bringing back to Europe as, ‘after Capt. Cook’s return home, it fetched 25 Guineas’. Interestingly, Sparrman’s journal from Society Islands (September 1773) also included a reflection on how inappropriate it was regarded for a European man to show sadness and cry, due to that ‘our civilised upbringing frequently demands us to control the most beautiful indication of emotions as being inimical to decent manliness.’ (This illustration was initially published in Anders Sparrman’s Swedish original edition of 1802 and the plate was named ‘Burial Ceremony on Otaheiti’). The final travelling apostle, Adam Afzelius (1750-1837), made his long voyage as a naturalist to Sierra Leone almost twenty years after Linnaeus’ lifetime, that is to say, in the mid-1790s. His detailed journal also includes some observations on mourning ceremonies and in what way textile materials were part of the local tradition. For instance, on 22 March in 1796, Afzelius had met the leader from a minor town whose wife had recently died in childbirth. She was wrapped in mats and rags before the body was lowered into a deep hole which was covered with earth. Mats of this type were plaited from bamboo or other large-leaved plants which grew in abundance. Regarding mourning of some close relative’s demise in the area, Afzelius was keen to study the differences in dress between the various population groups in the previous year. On 22 April 1795, he wrote from Sherbró. ‘When they are in mourning, then even the girls put on a blue cloth, contrary to what they do on Bullamshore, where you will see old women in mourning stripped naked only with something round their waist, a white cap on their head and the face and legs painted white’.

Whilst the naturalist Daniel Solander’s (1733-1782) problems when arriving to London was that everything was so very expensive at this place, something which he mentioned in a letter to Carl Linnaeus on 31 August in 1760, particularly because of the necessity to purchase new clothes. He had had made up for him, ‘suits, one in colour and two in black and an English overcoat’. The black broadcloth had turned out to be extra costly due to a price rise as a result of increased demand for the cloth after the death of King George II. An enlightening detail giving evidence for that a death of a king could effect the prices of cloth. This engraving was probably a commemorative depiction of George II, King of Great Britain (1683-1760) shortly after his death. (Courtesy of: New York Public Library, Emmet Collection. no. 419814. Wikimedia Commons).

Whilst the naturalist Daniel Solander’s (1733-1782) problems when arriving to London was that everything was so very expensive at this place, something which he mentioned in a letter to Carl Linnaeus on 31 August in 1760, particularly because of the necessity to purchase new clothes. He had had made up for him, ‘suits, one in colour and two in black and an English overcoat’. The black broadcloth had turned out to be extra costly due to a price rise as a result of increased demand for the cloth after the death of King George II. An enlightening detail giving evidence for that a death of a king could effect the prices of cloth. This engraving was probably a commemorative depiction of George II, King of Great Britain (1683-1760) shortly after his death. (Courtesy of: New York Public Library, Emmet Collection. no. 419814. Wikimedia Commons).

The naturalist Pehr Kalm (1716-1779), on the other hand, had stayed for some months in London during the year 1748, prior to his North American travels in the colonies of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Delaware and the southeastern parts of what is today Canada. On 13 May, he even mentioned that he had happened to see George II in his carriage close to the Parliament building. However, a note in his journal related to death and linen fabric was written on the crossing over the Atlantic Ocean on 11 September: ‘At 4.15 o’cl. one of the passengers called Wheeler died, a sailmaker who had been sickly throughout the voyage; and at 8 o’cl. following that he was buried in the customary manner of mariners by reading some prayers and then throwing the body, sewn into a hammock with a bag of coal by the feet, overboard into the sea.’ Kalm himself seems, on the whole, to have been contented with his existence and did not suffer any other serious illness than seasickness, mosquito bites and toothache. He lived for nearly thirty years after his return home in the summer of 1751 and, therefore, had the possibility to revise the results of his research and publish large parts of his journal.

Sources:

- Ekeberg, Carl Gustaf, Ostindiska resa åren 1770 och 1771…, Stockholm 1773 (pag. 8).

- Hallberg, Paul & Olsson, S. Bertil ed., En ostindie farande fältskärs berättelse – Carl Fredrik Adlers journal från skeppet Prins Carl 1753-56, Göteborg 2013.

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012. (Journal quotes: Vol. Three: Pehr Kalm. Vol. Five: Anders Sparrman. Vol. Six: Carl Peter Thunberg. Vol. Seven: Pehr Osbeck).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 87-88, 103-107, 203, 245 & 259).

- Mihles, Samuel, The elements of surgery... Adapted to the use of the camp and navy... London 1764.

- Osbeck, Peter [Pehr], A Voyage to China and the East Indies, 2 vol., London 1771.

- Sparrman, Anders, Resa omkring Jordklotet, I sällskap med Kapit. J. Cook och Hrr Forster. Åren 1772, 73, 74 och 1775…Första afdelningen, Stockholm 1802.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE