ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

HISTORICAL REPRODUCTIONS

– A Case Study of Swedish Samplers and Embroidery Traditions

For several centuries, it was part of educational needlecraft for girls and young women of aristocratic, bourgeoise and priest families in many countries to embroider a sampler. Such hands-on skills were mainly acquired in their domestic sphere as an important step towards adulthood, intertwined with other handicrafts, reading, correspondence, musical talents, etc. To a lesser extent, such embroidery was learned in schools for poor girls. The earliest known preserved samplers from Sweden originate from the early 18th century. Whilst, the tradition of making a selection of small embroidered pieces of various techniques and patterning on the same fabric was evidently in practice already during the previous two centuries in England and some other areas. The aim of this essay is to share the experience of reproducing a sampler embroidered with cotton thread on fine linen, together with a brief historical introduction of influences, patterns, materials and used stitches.

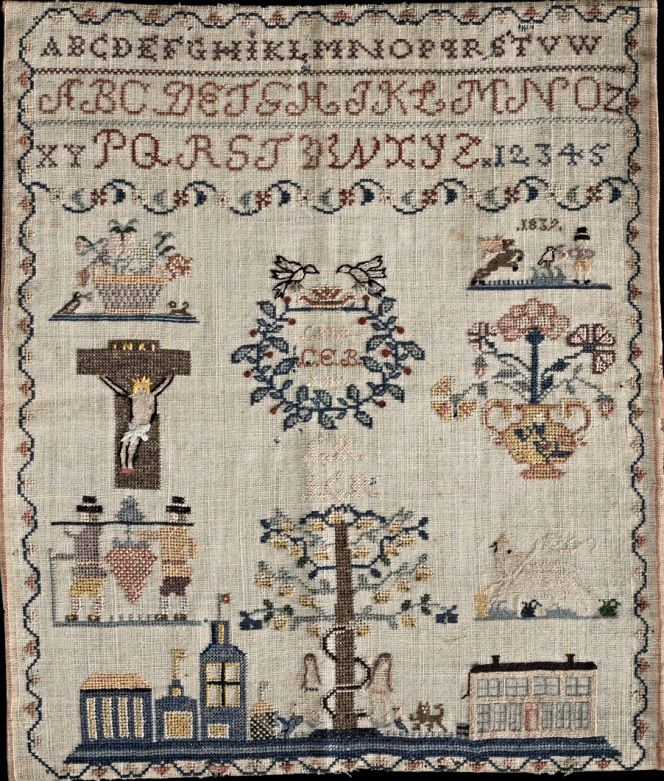

A well-preserved sampler, embroidered on plain-woven woollen fabric (14 threads/cm) with natural dyed silk threads of many colours. The unknown embroiderer’s initials ‘C.E.B’ was placed within a wreath with opposite standing birds, the year ‘1839’ is likely to be the year it was finalised. Religious motifs were combined with flower baskets, buildings, alphabets etc in a frame shaped like a creeper with flowers. On this example, as well as on many other Swedish samplers, it may be noted that the alphabet ends on ‘Z’. Maybe the international influence on such embroideries, contributed to that the Swedish letters Å, Ä and Ö at the end of the alphabet were excluded. Furthermore, this particular embroidery must have been complex as well as time-consuming to make, which indicate that the girl probably was at least 12 to 14 years of age. In the main she used cross stitch with additional effects of petit points, satin stitch and hemstitch. This is one of several hundred samplers kept at the Nordic Museum – chosen to exemplify a typical 19th century design which also is quite similar in style to my reconstruction, illustrated below. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0134065.1. Digitalt Museum).

A well-preserved sampler, embroidered on plain-woven woollen fabric (14 threads/cm) with natural dyed silk threads of many colours. The unknown embroiderer’s initials ‘C.E.B’ was placed within a wreath with opposite standing birds, the year ‘1839’ is likely to be the year it was finalised. Religious motifs were combined with flower baskets, buildings, alphabets etc in a frame shaped like a creeper with flowers. On this example, as well as on many other Swedish samplers, it may be noted that the alphabet ends on ‘Z’. Maybe the international influence on such embroideries, contributed to that the Swedish letters Å, Ä and Ö at the end of the alphabet were excluded. Furthermore, this particular embroidery must have been complex as well as time-consuming to make, which indicate that the girl probably was at least 12 to 14 years of age. In the main she used cross stitch with additional effects of petit points, satin stitch and hemstitch. This is one of several hundred samplers kept at the Nordic Museum – chosen to exemplify a typical 19th century design which also is quite similar in style to my reconstruction, illustrated below. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm. NM.0134065.1. Digitalt Museum).It was regarded as essential for girls from about six to fourteen years old to learn the art of embroidery regardless of social belonging. Either to enable them to earn a living one day through skill in needlework and embroidery, to be able to decorate textiles with beautiful embroidery for their dowry, or simply to have a suitable way of filling otherwise unproductive hours. They would learn to embroider mainly at home, from mother to daughter, grandmother to granddaughter or from other female relatives or servants in the household.

Though from 1842, an elementary school for all was introduced in Sweden, it took 50 years, up to 1892, before “girls' handicraft” was introduced as a compulsory subject. Girls, by now, learned to embroider, mark linen, sew simple garments, knit and crochet – basic textile knowledge which was seen as invaluable for a girl to master. However, in some places, education was not available prior to this time. In Malmö, for instance, in southernmost Sweden, there was a possibility for poor girls to learn embroidery, etc, at Josefinas slöjdskola (Josefin’s handicraft school), which had already opened in 1839. This school still existed in 1892, but the previous poor relief aim came to an end, and the establishment became a domestic handicraft/cooking school, which continued for about twenty years. The extent to which the embroidering of samplers was practised at this school over the years is unknown. In contrast to a school for girls, which started in 1813 at Clara parish in Stockholm, from where the late textile historian Karin Landergren-Blomqvist traced evidence of sampler making via yearly school reports:

- ‘In the first report of the school, it is mentioned that two girls only, one 13-year old, the second oldest pupil of the school, and one 11-year old, had started on their samplers. From year 1821 until the school closed in 1861, there was a special sewing department. This included one “embroidery section” of eight classes, one “knitting section” of five classes, one “spinning section” of six classes and finally one “revision section”. The final work the girls were obliged to do in the embroidery section, before continuing to the knitting section, was to make a sampler. In the curriculum, it was stated that the pupils before this had practised the stitches, first on paper and thereafter on pieces of cloth.’ (Quote in translation from Swedish, p. 101. See sources).

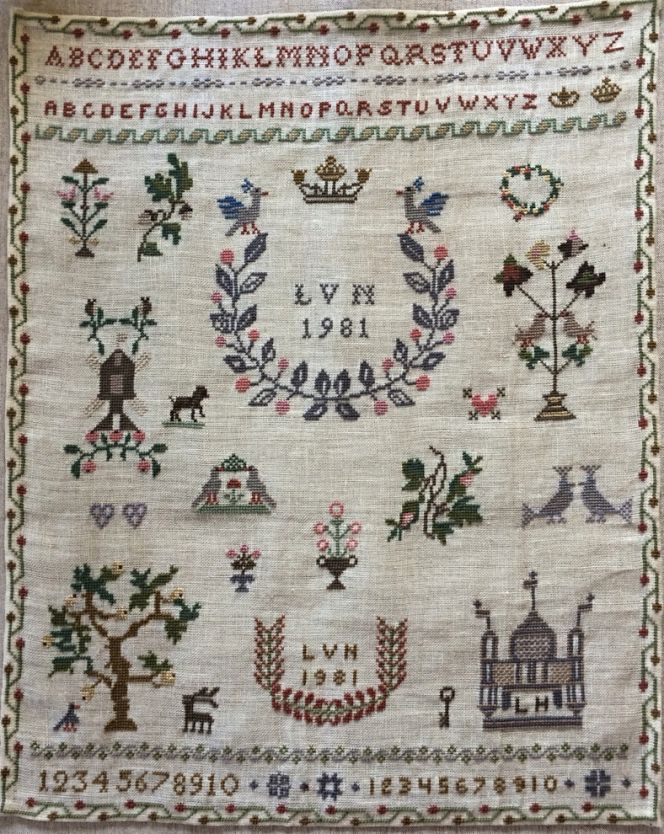

For a reconstruction it is advisable to embroider the frame first from my experience, followed by alphabets and numbers to get the structure correctly laid out. Whereafter the large and small wreaths (with the initials of my two first names and maiden name) are centred, finally the various motifs are quite easily embroidered in each and every desired position. In contrast to 19th century samplers which often included a variation of stitching, this reconstruction may be regarded as somewhat simplified as cross stitch only was used. Whilst the fineness of the fabric (14 threads/cm) and cotton yarn in 20 colours are comparable to such originals. However, if looking further back in time to the 18th century, most samplers had an even greater complexity, mainly due to the preference of an extremely fine linen or woollen fabric with suitably thin silk threads. (Private ownership of embroidery, made 1981). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

For a reconstruction it is advisable to embroider the frame first from my experience, followed by alphabets and numbers to get the structure correctly laid out. Whereafter the large and small wreaths (with the initials of my two first names and maiden name) are centred, finally the various motifs are quite easily embroidered in each and every desired position. In contrast to 19th century samplers which often included a variation of stitching, this reconstruction may be regarded as somewhat simplified as cross stitch only was used. Whilst the fineness of the fabric (14 threads/cm) and cotton yarn in 20 colours are comparable to such originals. However, if looking further back in time to the 18th century, most samplers had an even greater complexity, mainly due to the preference of an extremely fine linen or woollen fabric with suitably thin silk threads. (Private ownership of embroidery, made 1981). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Surplus linen and cotton yarn together with the sketch for the reconstruction of the sampler in cross stitch, still preserved among my handicraft material since 1981! Notice the rather subdued colours, which even if chemically dyed were aiming to reconstruct the impression of a sampler prior to the 1850s – at a time when natural dyes only were in use. The motifs and design for this sampler had been copied and to some extent adapted after an old (c.1780s-1830s) sampler by the Handicraft Organisation of Malmö in 1958. To my knowledge, it is unknown where this original embroidery is kept today. (Private ownership). Photo Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Surplus linen and cotton yarn together with the sketch for the reconstruction of the sampler in cross stitch, still preserved among my handicraft material since 1981! Notice the rather subdued colours, which even if chemically dyed were aiming to reconstruct the impression of a sampler prior to the 1850s – at a time when natural dyes only were in use. The motifs and design for this sampler had been copied and to some extent adapted after an old (c.1780s-1830s) sampler by the Handicraft Organisation of Malmö in 1958. To my knowledge, it is unknown where this original embroidery is kept today. (Private ownership). Photo Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.The reproduction of this sampler was made in my later teenage years, that is to say, being somewhat older than the girls who originally practised their embroidery skills via these samplers. I found enjoyment in the practical embroidering on fine linen and remember choosing this particular design due to the wide range of beautiful colours. It may be noted that this is no exact copy of a historical sampler, which coincides quite well with the much earlier traditions. Judging by extensive collections of preserved Swedish 18th-19th century samplers, most embroiderers seem to have followed strict standards with similar patterns. Even if every girl and young woman also added unique features or rearranged the patterning from previous models they studied via friends, older relatives or printed pattern books – the two samplers never became identical.

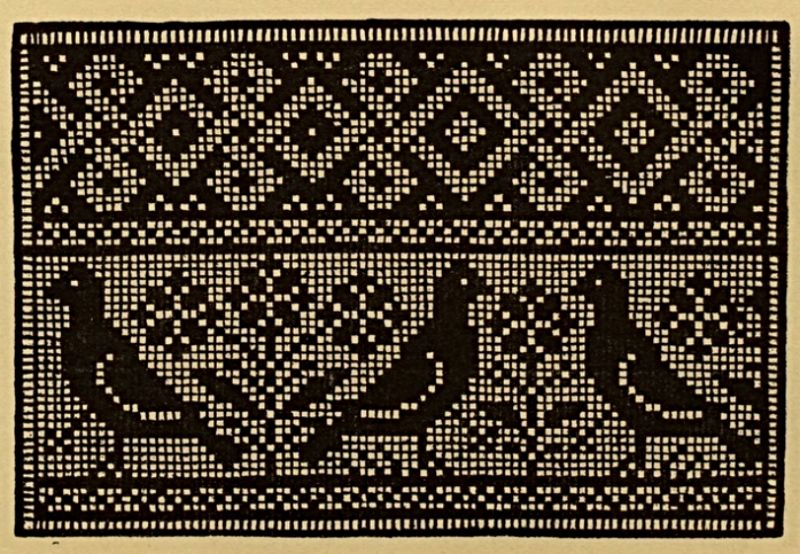

One of many motifs depicted in ‘Buratto, a Book of Embroidery’ printed in 1527 is the opposite standing birds – a design frequently used long before as well as after this early book was printed. Such books for embroidery in the 16th and 17th centuries, seems to have been an important source of inspiration for reasonable well-to-do households of the nobles, bourgeoise and priests who could afford to buy books. Such motifs in the most varied combinations were well rooted as artistic depictions in all strata of society during 19th century Sweden and many other European countries alike. One popular area of use was to pick details chosen after each and every young girl’s or young woman’s preferences for embroidered samplers. (From: Paganino, Alessandro…p. 68. Online source).

One of many motifs depicted in ‘Buratto, a Book of Embroidery’ printed in 1527 is the opposite standing birds – a design frequently used long before as well as after this early book was printed. Such books for embroidery in the 16th and 17th centuries, seems to have been an important source of inspiration for reasonable well-to-do households of the nobles, bourgeoise and priests who could afford to buy books. Such motifs in the most varied combinations were well rooted as artistic depictions in all strata of society during 19th century Sweden and many other European countries alike. One popular area of use was to pick details chosen after each and every young girl’s or young woman’s preferences for embroidered samplers. (From: Paganino, Alessandro…p. 68. Online source). Printed books including inspiration for embroidery, weaving and other handicraft were mainly published in Italy, France and Germany during the 16th century. Such publications often illustrated stars, rosettes, runners, flowers, palmettes, opposite standing birds and other ornamental figures. The tradition continued through the centuries and spread to other countries, here illustrated with a Swedish weaving book printed in 1828. Even if this particular book primarily was intended for complex diaper and damask weaving, single motifs as well as various designs could equally be adapted for embroidering of samplers in cross stitch. Here exemplified with one of ten beautiful foldouts. (From: Ekenmark J.E…1828 Pl. 6. Private ownership). Photo Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Printed books including inspiration for embroidery, weaving and other handicraft were mainly published in Italy, France and Germany during the 16th century. Such publications often illustrated stars, rosettes, runners, flowers, palmettes, opposite standing birds and other ornamental figures. The tradition continued through the centuries and spread to other countries, here illustrated with a Swedish weaving book printed in 1828. Even if this particular book primarily was intended for complex diaper and damask weaving, single motifs as well as various designs could equally be adapted for embroidering of samplers in cross stitch. Here exemplified with one of ten beautiful foldouts. (From: Ekenmark J.E…1828 Pl. 6. Private ownership). Photo Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.To a greater extent, the earlier samplers (up to the first decade of the 19th century) were made on a finer weave, thus using smaller stitches, sometimes sewn with extremely petite cross stitches over a single thread. These early samplers more often contained several different kinds of stitches, making the work more difficult and demanding greater skill of the embroiderer. There seems to have been a similar tradition in Sweden and several other European countries. Even if samplers lost their importance as teaching material early in the 20th century, taking an interest in them has contributed to a growing knowledge of historical embroidery and attempts to copy them have continued in our own time. But the problem with copying samplers – particularly if the model dates from the beginning of the 19th century or earlier – is that today, we cannot find woven plain linen, or silk, wool, linen or cotton yarn as fine in quality as that spun by hand in those days.

Sources:

- Ekenmark J.E. och Systrar, Afhandling om Drällers och Dubbla Golfmattors tillverkning… Stockholm 1828.

- Hansen, Viveka (Historical reproduction of sampler, in 1981).

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Fyra sekel Malmö textil – 1650 till 2000’, Elbogen, pp. 23-91, 1999 (p. 61).

- Landergren-Blomqvist, Karin, ‘Märkdukarnas alfabet’, Kulturen, 1962 (pp. 99-118).

- Malmöhus Läns Hemslöjdsförening (Handicraft Organisation: Purchase – in 1981 – of cotton thread, linen & pattern for the reproduction).

- Nylén, Anna-Maja, Hemslöjd, Lund 1969 (pp. 215-218).

- Paganino, Alessandro, Il Burato, Libro de Recami, [1527] Facsimile 1909 (p. 68).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History from a textile Perspective.

Open Access essays, licensed under Creative Commons and freely accessible, by Textile historian Viveka Hansen, aim to integrate her current research, printed monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays feature rare archive material originally published in other languages, now available in English for the first time, revealing aspects of history that were previously little known outside northern European countries. Her work also explores various topics, including the textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion, natural dyeing, and the intriguing world of early travelling naturalists – such as the "Linnaean network" – viewed through a global historical lens.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE