ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

JAPANESE GARDENS, DYES AND SILK

– The Naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg’s Observations in the 1770s

The naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg made innumerable observations of Japanese society, gardens, textile raw material, natural dyeing, peoples’ ways of living and cultural traditions, as well as scientific descriptions of natural history significance. It must be borne in mind that only very few Europeans were permitted to travel further than the port of Nagasaki in the 18th century. It appears, therefore that the traveller made full use of that rare opportunity to study the lives of the Japanese from all conceivable angles. This case study will emphasise the connection between gardens, textile raw materials and natural dyeing as recorded from the Swedish naturalist’s perspective. Contemporary illustrations, together with Thunberg’s herbarium sheets and objects brought back home with him to Sweden after a nine year-year-long journey, will give some further thought to this context.

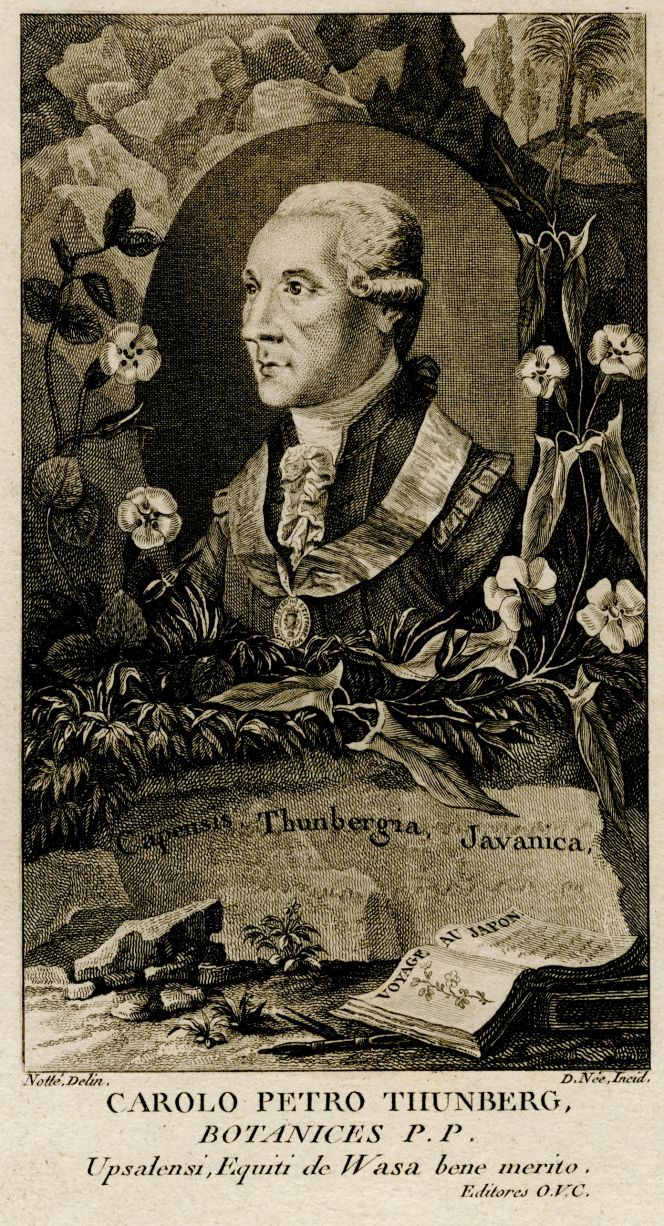

In this print, Carl Peter Thunberg wore a braided frock coat in the style of the national costume and the Royal Order of the Wasa after the nine-year-long voyage ending in 1779. Interestingly, Gustaf III introduced the national costume the year before, so it is likely that this portrait originated from around 1780, even if the print itself was included in the French edition of Thunberg’s journal, published in 1796. Notable is that several similar portraits of Thunberg, with various frames, were included in several editions of his publications in the late 18th century. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin. record. 97273. Public Domain).

In this print, Carl Peter Thunberg wore a braided frock coat in the style of the national costume and the Royal Order of the Wasa after the nine-year-long voyage ending in 1779. Interestingly, Gustaf III introduced the national costume the year before, so it is likely that this portrait originated from around 1780, even if the print itself was included in the French edition of Thunberg’s journal, published in 1796. Notable is that several similar portraits of Thunberg, with various frames, were included in several editions of his publications in the late 18th century. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. Alvin. record. 97273. Public Domain).Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) – as one of Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) pupils – had set his sights on extending his geographical horizon in the service of science once his studies were completed. His journey started in August 1770; assisted by a bursary he had been granted and a recommendation from Linnaeus, he travelled via Helsingborg and København to Amsterdam, where he remained for over a month. After his return from a good seven months stay in Paris in 1771, he accepted an offer, and it was decided that his continual botanical voyage and work would be as a surgeon for the Dutch East India Company (VOC) on a ship sailing towards Japan, an area largely unexplored from a European perspective. The conditions prevailing at the time meant that he was forced to present himself as a Dutchman, and no other Europeans were allowed to visit Japan. The Dutch language was therefore something Thunberg had to learn, and it was for that reason considered suitable for him first to spend some years in the Dutch colony in the Cape area. First, in March 1775, the voyage continued towards Japan, with a month’s stay in the important Dutch maritime trading centre Batavia [today Jakarta], the group arriving in Nagasaki in August.

For over two hundred years, from 1638-1853, Japan had been a country with limited travel possibilities in and out of the country; the area had developed traditions without its equal in other parts of eastern Asia. That did not mean that the country was isolated or closed as, for instance, imported fabrics of Chinese make and textiles brought in via the Dutch East India Company trade were very popular in Japan. Gift exchange, diplomacy, and trade were deeply intertwined. At the time of Thunberg’s visit during the years of 1775 and 1776, some restricted trading had been a reality for nearly 150 years. Those circumstances contributed to unique craft traditions being developed for textiles of silk and cotton, further processed using several advanced techniques to achieve special effects and applications. Thunberg also recorded the great significance those two raw materials had for the people in his account of the country’s ‘Agriculture’:

- ‘...the cultivation of Cotton and Silk, is an object of the greatest importance in this country, and furnished the clothing of many millions. For this purpose they cultivate and plant every year the cotton shrub (Gossypium herbaceum), which yields a very fine and white cotton, fit for cloths, wadding, and other uses. The cultivation of Silk depends upon the planting and propagation of the Mulberry tree, by means of which an incredible number of Silk-worms are bred, and the raw silk produced, of which are made silken pieces of stuff, thread, wadding, and a great many more articles, both of ornament and use.’

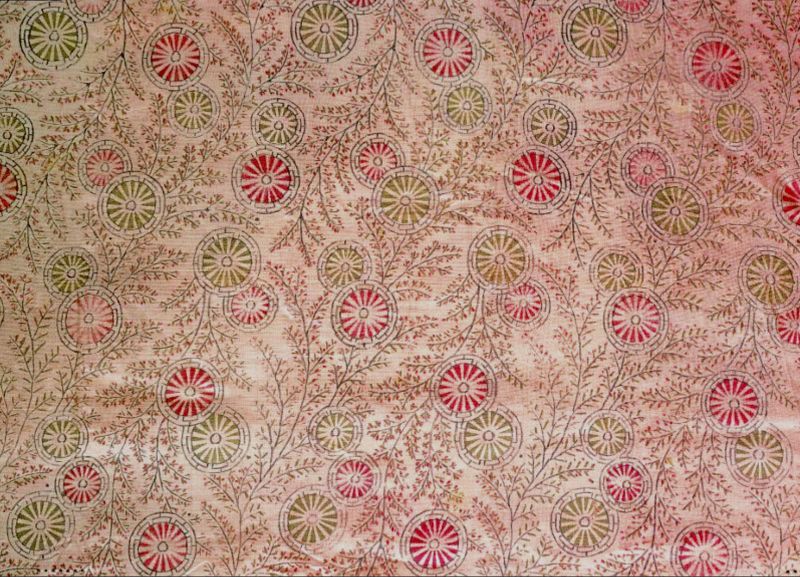

Thunberg also observed how red colours were obtained using plants for textile dyeing. His travel journal gave an account of how people in the provinces dyed red using Rubia cordata, related to common madder, Rubia tinctorum, which the Swedish dyers, like many dyers from other countries, used for the production of red yarns and fabrics. This nightgown – which among other colours, was probably block printed red with Rubia cordata – a garment Thunberg brought back from Japan, also mentioned in his travel journal. The wadded garment – has a wheel motif with floral garlands – on plain woven silk. (Courtesy: Thunberg Collection, Museum of Ethnography, Sweden. No. 1874.1.87).

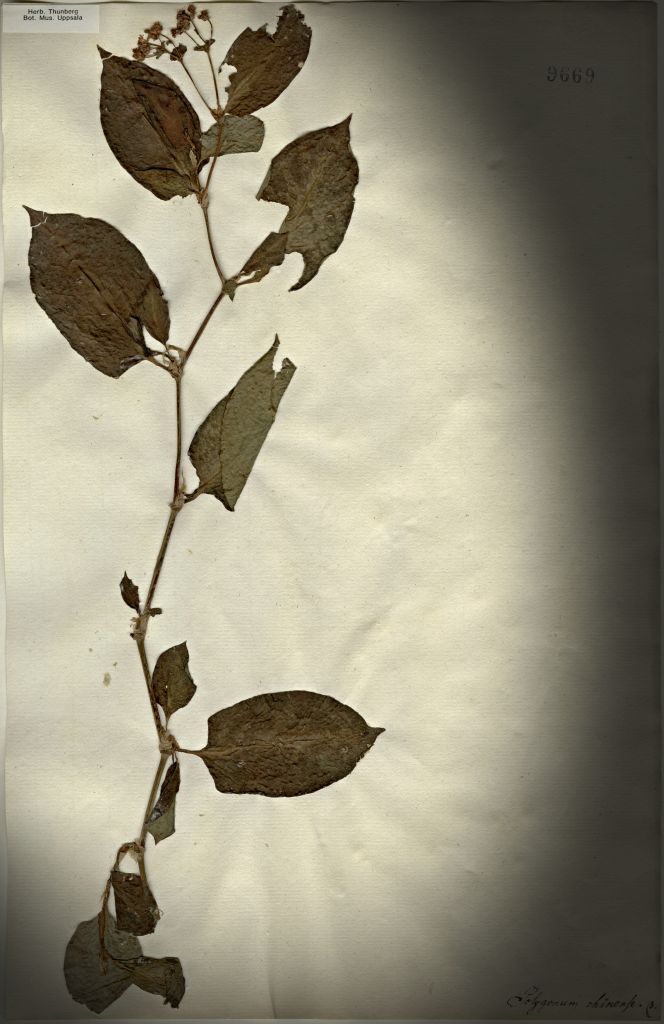

Thunberg also observed how red colours were obtained using plants for textile dyeing. His travel journal gave an account of how people in the provinces dyed red using Rubia cordata, related to common madder, Rubia tinctorum, which the Swedish dyers, like many dyers from other countries, used for the production of red yarns and fabrics. This nightgown – which among other colours, was probably block printed red with Rubia cordata – a garment Thunberg brought back from Japan, also mentioned in his travel journal. The wadded garment – has a wheel motif with floral garlands – on plain woven silk. (Courtesy: Thunberg Collection, Museum of Ethnography, Sweden. No. 1874.1.87).  Several different species were mentioned as being cultivated for the purpose of dyeing blue. The colours of ‘Polygonum chinense, barbatum and aviculare’ were similar to indigo. | Herbarium sheet with Polygonum chinense – current name Persicaria chinensis (L.), collected by Thunberg in Japan in the 1770s. (Courtesy: Museum of Evolution, Uppsala, Sweden. No. 9669. Thunberg Herbarium).

Several different species were mentioned as being cultivated for the purpose of dyeing blue. The colours of ‘Polygonum chinense, barbatum and aviculare’ were similar to indigo. | Herbarium sheet with Polygonum chinense – current name Persicaria chinensis (L.), collected by Thunberg in Japan in the 1770s. (Courtesy: Museum of Evolution, Uppsala, Sweden. No. 9669. Thunberg Herbarium). How the dyestuff of ‘Polygonum chinense, barbatum and aviculare’ were prepared, sold and used is described under the headline ‘Agriculture’ in Thunberg’s travel journal: ‘The leaves were first dried, then pounded, and made into small cakes, which were sold in the shops. With these, I was told, they can dye linen, silk, and cotton. When they boil them up for use, they add ashes to them; and the stronger the decoction is made, of so much the darker blue is the colour obtained; and vice versa.’ A few dye-plants can also be studied in his Latin Flora Japonica: indigo (Indigofera tinctoria) for dyeing blue, saw-wort (Serratula tinctoria) for yellow and safflower (Carthamus tinctoria) the flowers of which dyed silk yellow. The Japanese flora did, in other words, contain within itself the great potential for producing colours, extremely durable against sun, laundering and general wear and tear without the need to import any dyes. Safflower was moreover named ‘bastard saffron’ in his travel journal from Dezima, while the genuine saffron (Crocus sativus) was listed several times as a substantial trading commodity between the Dutch and the Japanese, but nothing was mentioned of the dyeing properties of the plant on fabrics and yarn. Another aspect of dyeing blue from Thunberg’s stay in Japan can be seen in a pair of indigo-dyed trousers and the waistcoat of the same fabric that goes with them, which were brought back home as ethnographic items. The garment is described as follows by the Museum of Ethnography: ‘Hakkama, woven from plant fibre (hemp?) in a plain weave of a light blue indigo colour, designed with a scatter of small floral patterns and a white circle with a leaf painted in Indian ink inside. Traditionally cut with a stiffener in the band at the back, starched or smoothed’.

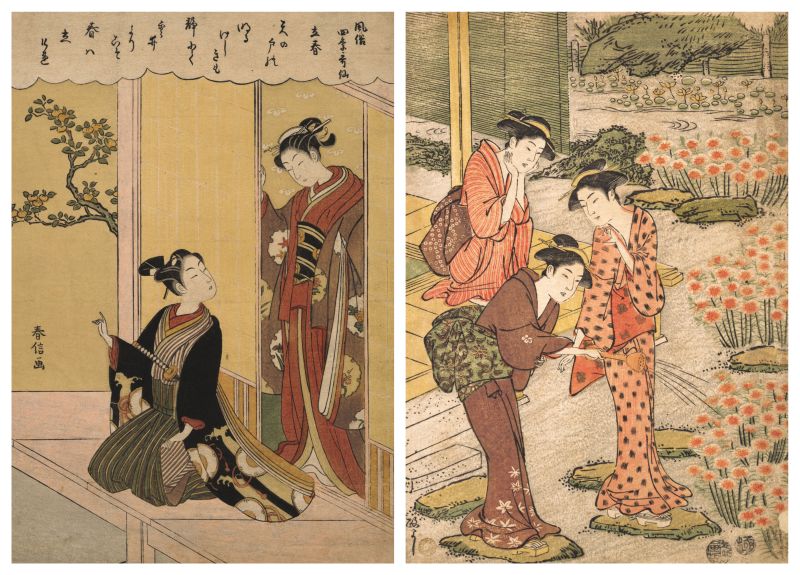

To the left, a beautiful coloured print, probably from circa 1768, displays great similarities with Thunberg’s journal note of the dress of the prosperous Japanese women and men. From Dezima in 1776, he even recorded the same species of oranges – as visible on this print – and how these plants were treasured in the gardens: ‘A very small species of China Orange (Citrus Japonica), is frequently cultivated in the houses in pots. This shrub hardly exceeds six inches in height, and its fruit, which is sweet and palatable, like China Oranges, is not larger than an ordinary Cherry.’ Overall, attention to detail was an important element in all traditional gardening in Japan. | The righthand print continues on the same theme. Instead, it illustrates the large pink (Dianthus superbus) and three young women in a garden with stepping stones and areas of growing moss – all carefully kept in the fenced garden around 1790. Interestingly, another species within the same Genus (Dianthus japonicus) was recorded by Thunberg in his volume ‘Flora Japonica’. (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, US. To the left: No. JP2776. Artist Suzuki Harunobu (1725-1770), woodblock print; ink and colour on paper. Edo period, Japan & to the right: No. JP193. Artist Kuwagata Keisai (1764-1824), woodblock print; ink and colour on paper. Edo period, Japan).

To the left, a beautiful coloured print, probably from circa 1768, displays great similarities with Thunberg’s journal note of the dress of the prosperous Japanese women and men. From Dezima in 1776, he even recorded the same species of oranges – as visible on this print – and how these plants were treasured in the gardens: ‘A very small species of China Orange (Citrus Japonica), is frequently cultivated in the houses in pots. This shrub hardly exceeds six inches in height, and its fruit, which is sweet and palatable, like China Oranges, is not larger than an ordinary Cherry.’ Overall, attention to detail was an important element in all traditional gardening in Japan. | The righthand print continues on the same theme. Instead, it illustrates the large pink (Dianthus superbus) and three young women in a garden with stepping stones and areas of growing moss – all carefully kept in the fenced garden around 1790. Interestingly, another species within the same Genus (Dianthus japonicus) was recorded by Thunberg in his volume ‘Flora Japonica’. (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, US. To the left: No. JP2776. Artist Suzuki Harunobu (1725-1770), woodblock print; ink and colour on paper. Edo period, Japan & to the right: No. JP193. Artist Kuwagata Keisai (1764-1824), woodblock print; ink and colour on paper. Edo period, Japan).Thunberg also recorded the great significance of the tea garden during the Edo period – a garden which introduced the right state of mind for the visitor before entering the tea ceremony. Everyday life, religion and symbolism were all deeply intertwined in the carefully displayed small gardens close to the home – including rocks, stepping stones, mosses, plants and water features. A number of passages from his travel journal will further emphasise his detailed observations of various elements, practical arrangements, useful fruit, vegetable and medicinal plants for the household, and the beauty and well-being experienced in the Japanese gardens. In Dezima and Nagasaki, for instance, garden cultivation was necessary for the local inhabitants equally as the crew of the Dutch East India Company ships, as recorded in February 1776:

- ’In the gardens, as well in as out of the town, I observed several European culinary vegetables cultivated, and of these I had already seen some carried on board the Dutch ship and to the factory. Of this kind, were Red Beet (Beta vulgaris), the root of which was of a deeper red than any I had ever seen at any other place out of Europe; Carrots (Daucus Carota), Fennel (Anethum faeniculum) and Dill (Anethum graveolens), Anise (Pimpinella Anisum), Parsley (Apium petroselinum), Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis); several bulbous plants, such as Leeks, Onions, and others (Alium fistulosum, Cepa); Turnips (Brasica rapa), Black Radishes (Raphanus), Lettuce (Lactuca sativa), Succory and Endive (Cichorium Intybus & Endivia), besides many more…The Alcea rosea and the Malva Mauritiana were frequently found cultivated in small gardens in the town for the sake of their large and elegant flowers.’

When the ambassadors et al. set out from Dezima on a journey to the Japanese court, Thunberg gave the most positive note in March 1776 from Kokura, about tranquil stays with access to gardens during their travels:

- ‘Here, as well as at all the other inns, we were lodged in the back part of the house, which is not only the most convenient, but the pleasantest part, always having an outlet and view into a backyard, larger or smaller, which is embellished with various trees, shrubs, plants, and flower pots. On one side of this spot, there is also a small bath for strangers to bathe in if they choose. Amongst other things that were common in several places, such as the Pinus Sylvestris, Azalea Indica, Chrysanthemum Indicum, &c. I also found here a tree, which is called Aukuba, and another called Nandina, both which were supposed to bring good fortune to the house.’

![Map of Kyoto [imperial capital, Miaco] during the Edo period, dated to circa 1772-76, a map which was brought back by Thunberg to Sweden in 1779. In the context of this essay, it is noticeable how gardens were uniformly outlined with tree designs and placed close to each and every marked house on the map. Furthermore, when staying in Miaco (April 1776), he observed the strict ceremonial traditions linked to gardens. ‘When the Dairi at any time leaves his apartments in order to walk in the gardens, it is made known by signs, to the end, that no one may approach to see this country’s quondam ruler, now merely its pope, vested with power in ecclesiastical matters only, but who is considered as being so holy, that no man must behold him. During the few days we stayed here, his holiness was pleased once to inhale the pure air out of doors when a signal was given from the wall of the castle.’ (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Uppsala, Sweden. Alvin-record. 91734. Public Domain).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/5a-thunberg-map-800x583.jpg) Map of Kyoto [imperial capital, Miaco] during the Edo period, dated to circa 1772-76, a map which was brought back by Thunberg to Sweden in 1779. In the context of this essay, it is noticeable how gardens were uniformly outlined with tree designs and placed close to each and every marked house on the map. Furthermore, when staying in Miaco (April 1776), he observed the strict ceremonial traditions linked to gardens. ‘When the Dairi at any time leaves his apartments in order to walk in the gardens, it is made known by signs, to the end, that no one may approach to see this country’s quondam ruler, now merely its pope, vested with power in ecclesiastical matters only, but who is considered as being so holy, that no man must behold him. During the few days we stayed here, his holiness was pleased once to inhale the pure air out of doors when a signal was given from the wall of the castle.’ (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Uppsala, Sweden. Alvin-record. 91734. Public Domain).

Map of Kyoto [imperial capital, Miaco] during the Edo period, dated to circa 1772-76, a map which was brought back by Thunberg to Sweden in 1779. In the context of this essay, it is noticeable how gardens were uniformly outlined with tree designs and placed close to each and every marked house on the map. Furthermore, when staying in Miaco (April 1776), he observed the strict ceremonial traditions linked to gardens. ‘When the Dairi at any time leaves his apartments in order to walk in the gardens, it is made known by signs, to the end, that no one may approach to see this country’s quondam ruler, now merely its pope, vested with power in ecclesiastical matters only, but who is considered as being so holy, that no man must behold him. During the few days we stayed here, his holiness was pleased once to inhale the pure air out of doors when a signal was given from the wall of the castle.’ (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Uppsala, Sweden. Alvin-record. 91734. Public Domain).On the 25 May, the travel company left the court to travel back towards Nagasaki where Thunberg made a note about beauty and planting in pots: ‘Several places also they had, Acrostichum hastatum, planted in pots for pleasure, although it is with great difficulty that this species of plant is raised in Europe.’ When reaching Osaka, where they stayed for two days in June, his travel journal not only reveals how the gardens were designed but also the importance of his own collecting of plants during his time in Japan:

- ‘Those that I, for my part, most valued were a collection of Japanese plants in a well-ordered garden, a collection of birds indigenous to this country, and the casting of their copper into bars…I saw in the street called Bird-street, a number of birds that had been brought hither from all parts, some to be shown for money and others for sale. There was also a botanic garden tolerably well laid out in this town (though without an orangery) in which were reared and cultivated and at the same time kept for sale, all sorts of plants, trees, and shrubs, which were brought hither from other provinces. I did not neglect to lay out as much money here as I could spare in the purchase of the scarcest shrubs and plants, planted in pots, amongst which were the most beautiful species of this country’s elegant Maples, and two specimens of the Cycas revoluta, a Palm-tree, as scarce, as the exportation of it is strictly prohibited, and upon which, on account of its very nutritious Sago-like pith, the Japanese set so high, and, indeed, extravagant a value, not knowing that it likewise grows in China. These were afterwards all planted out into a large wooden box, at the top of which were laid boughs of trees interlaced with packthread so that nothing might injure them. This box was afterwards sent off by water to Nagasaki, from whence it was sent along with another box of the same kind, packed as the factory, to Batavia, to be forwarded to the Hortus Medicus in Amsterdam.’

Additionally, Thunberg gave the reader of his travel journal – in the chapter about Agriculture – further insight into the ornamental structure of gardening as well as the great variety of nutritious fruit grown in the Japanese gardens: such as Lemons, Seville and China oranges; Pears, Peaches, Plums, Cherries, Medlars – figs of a very delicious taste, Grapes, Pomegranates, Spanish Figs, Chestnuts, Walnuts, with a multiplicity of others.

In concluding words, today Thunberg is thought to have presented a somewhat idealised image of the country in his travel journal, unaware that the Japanese had constructed a well-polished façade in order to demonstrate happiness, wealth and cultural progressiveness to visitors along their routes when the reality was quite different for considerable numbers of the inhabitants. However, his positive observation of the Japanese gardens appears to be very true.

Sources:

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, 8 volumes, London & Whitby 2007-12 (Vol. Six. Carl Peter Thunberg’s travel journal).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (More about Carl Peter Thunberg’s textile observations over a nine-year journey, pp. 253-282).

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, US (Online information about the two woodblock prints No. JP2776 & JP193.

- Museum of Ethnography, Stockholm, Sweden. (Catalogue card information no. 1874.01.0058 & 1874.1.87, Thunberg’s Collection).

- Nordenstam, Bertil, ed., Carl Peter Thunberg – Linnean, resenär, naturforskare 1743-1828, Stockholm 1993.

- Skuncke, Marie-Christine, Carl Peter Thunberg: Botanist and Physician, Uppsala 2014.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Flora Japonica..., 1784.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE