ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

JAPANESE SAMPLE CATALOGUES

– Silk, Gold and Luxury in the 1870s

During a research visit to the Design Museum in Denmark, I examined two Japanese textile sample books dating from around the 1870s to 1880s with great interest. The meticulous attention to detail was exquisite in these traditionally hand-woven silk qualities – suitable for luxury clothing and interior textiles alike. Handloom weavers, skilled in these techniques, had learned from generation to generation, resulting in similarities in many methods and ornamentation that are nearly identical over several centuries. Notably, some brocades may have been woven on a jacquard loom, a novelty in Japan during this decade. However, to my knowledge, no detailed analysis has been carried out on these two Japanese sample catalogues held at the Design Museum, apart from general documentation of these uniquely preserved silk samples, which are also included in a book covering all known textile samples in Danish collections. Originally, such silks were designed for wealthy clients to order exclusive fabrics for clothing and other textile objects in late 19th-century Japan.

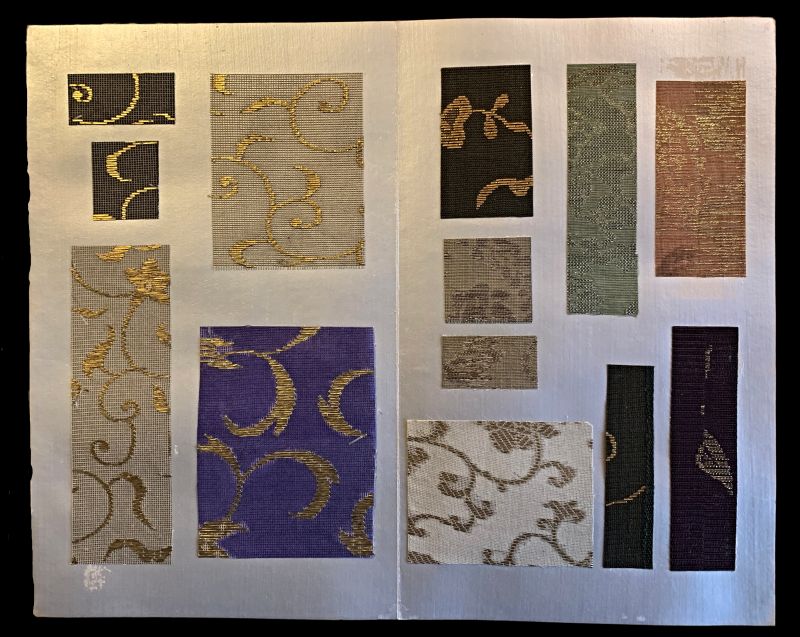

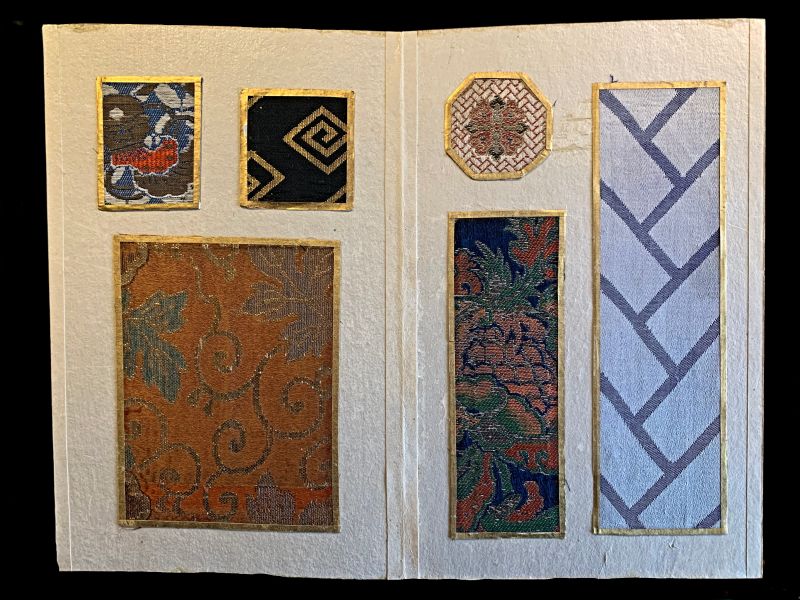

This is one of the double pages in a sample catalogue, where most fine silk qualities include metallic thread in the form of gold leaf. Using gold significantly increases the material cost and the complexity of the weaving. All the samples on the left-hand page were woven in gauze, a transparent plain weave, allowing for the creation of ornamental floating figures with metallic paper strips in the weft—a technique known as weft-dependent. The samples on the right-hand side have a similar design, with the only difference being a ribbed-structured ground. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. | The Library. Sample Book: I19072 Ø004). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

This is one of the double pages in a sample catalogue, where most fine silk qualities include metallic thread in the form of gold leaf. Using gold significantly increases the material cost and the complexity of the weaving. All the samples on the left-hand page were woven in gauze, a transparent plain weave, allowing for the creation of ornamental floating figures with metallic paper strips in the weft—a technique known as weft-dependent. The samples on the right-hand side have a similar design, with the only difference being a ribbed-structured ground. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. | The Library. Sample Book: I19072 Ø004). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.The long history of Japanese textile art is vividly explained and illustrated in various works, including the book Japanese Textiles in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It began in the 5th and 6th centuries AD, when many skilled textile artisans from Korea and China migrated to the Japanese islands. Around the same time, a significant import of silk cloth from these regions inspired and enhanced Japan's silk weaving knowledge. Over the next thousand years, silk weaving was continuously practised in several areas, notably Kyoto and Osaka. An intriguing historical fact about the exceptional expertise in the 15th century is comparable to fabric samples from around 1870, offering insights into the tradition of using gold leaf in such intricate weavings, as seen in the samples above.

- ‘Many weavers went to Sakai, a thriving port near present-day Osaka. Here, they came into contact with the newest textile imports from China, which enabled them to study techniques such as the use of applied metal foil (surihaku) and metallic paper strips (kinran and ginran), and the weaving of crepe (chirimen) and monochrome figured satins (rinzu).’ (Jackson 2002, quote p. 9)

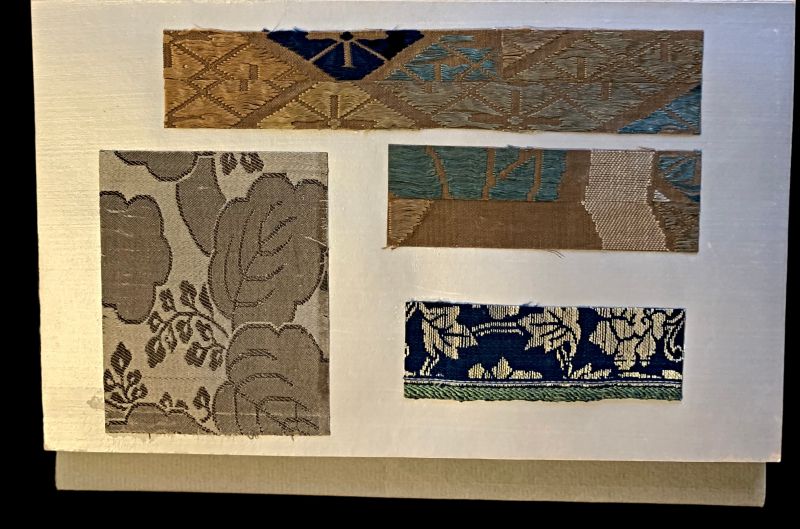

A close-up detail from the sample catalogue, including 22 pages, highlights the delicate silk brocade design style and colours used in this Japanese collection. The preferred choice of highly advanced weaving techniques is also visible here, with more than one warp system, resembling a figured satin weave. A decorative fabric like this, with relative sturdiness without long floating weft threads and great beauty, was often used for kimonos for centuries. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. |The Library. Sample Book: I19072 Ø004). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

A close-up detail from the sample catalogue, including 22 pages, highlights the delicate silk brocade design style and colours used in this Japanese collection. The preferred choice of highly advanced weaving techniques is also visible here, with more than one warp system, resembling a figured satin weave. A decorative fabric like this, with relative sturdiness without long floating weft threads and great beauty, was often used for kimonos for centuries. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. |The Library. Sample Book: I19072 Ø004). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. A second detail is quite different. A leaf motif in two colours was printed on plain-woven fibre ramie or hemp fabric. Decorating fabrics with dyes using various techniques has a long history in many countries, including Japan. For this particular sample, two stencils were used, one at a time, for the two red shades. The stencil design was relatively small due to the repetitive small leaf motif. It was also common to apply rice paste to the fabric before dyeing to protect the undyed ground, a paste that was easily washed away after the dyes had dried completely. Notably, this is the only dyed motif in the two studied sample catalogues. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. The Library. Sample Book: I19072 Ø004). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

A second detail is quite different. A leaf motif in two colours was printed on plain-woven fibre ramie or hemp fabric. Decorating fabrics with dyes using various techniques has a long history in many countries, including Japan. For this particular sample, two stencils were used, one at a time, for the two red shades. The stencil design was relatively small due to the repetitive small leaf motif. It was also common to apply rice paste to the fabric before dyeing to protect the undyed ground, a paste that was easily washed away after the dyes had dried completely. Notably, this is the only dyed motif in the two studied sample catalogues. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. The Library. Sample Book: I19072 Ø004). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. When the selvedge is visible in these sample catalogues, it shows a slight unevenness, indicating hand-weaving. For example, the blue fabric in the left-hand corner reveals that this complex figure twill quality with a double warp system was woven on a handloom. The two fabrics above illustrate a different technique with very long floating weft threads, which creates a shiny silk appearance but also results in a very delicate quality, almost unsuitable for clothing given their extraordinary complexity. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. (The Library. Sample Book: I19072 Ø004). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

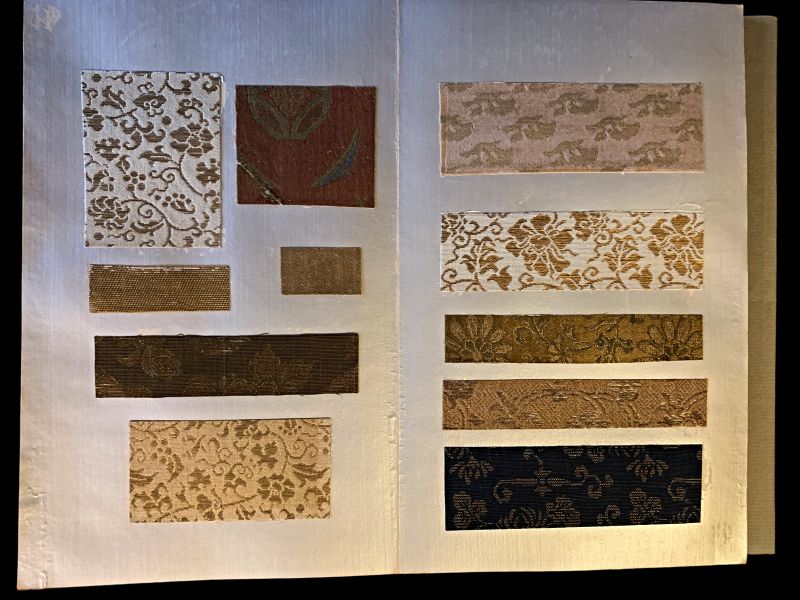

When the selvedge is visible in these sample catalogues, it shows a slight unevenness, indicating hand-weaving. For example, the blue fabric in the left-hand corner reveals that this complex figure twill quality with a double warp system was woven on a handloom. The two fabrics above illustrate a different technique with very long floating weft threads, which creates a shiny silk appearance but also results in a very delicate quality, almost unsuitable for clothing given their extraordinary complexity. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. (The Library. Sample Book: I19072 Ø004). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Over the centuries, during the Edo period (1603-1868) and even earlier, plain weave, net ground weave, ribbed fabric, or satin—often double warp and weft systems—have developed countless variations within these Japanese silk weaving traditions. Small, repetitive figures have consistently been among the most popular design groups. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. | The Library. Sample Book: I19072 Ø004). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Over the centuries, during the Edo period (1603-1868) and even earlier, plain weave, net ground weave, ribbed fabric, or satin—often double warp and weft systems—have developed countless variations within these Japanese silk weaving traditions. Small, repetitive figures have consistently been among the most popular design groups. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. | The Library. Sample Book: I19072 Ø004). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.Kyoto continued to be the foremost centre for luxury silk weaving during the Edo period, at a time when the Swedish naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg (1748-1828) may serve as an example of an observer of Japanese silk fabrics – as discussed in the previous essay, and here expanded with additional notes. He was the only one among the seventeen so-called Linnaeus Apostles to travel to the Japanese islands and meticulously recorded facts about textiles. Furthermore, from a European perspective, he was essentially the only one of his kind, as very few naturalists at that time had the opportunity to explore Japanese traditions. For this reason, his travel journal remains an entirely unique record of textile studies in Japan during the 1770s, seen through both the eyes of a Swede and a European naturalist.

Having existed for over two hundred years, from 1603 to 1853, and being a country with limited travel possibilities into and out of Japan, the nation developed a textile tradition unmatched in other parts of eastern Asia. However, this did not mean that the country was isolated or closed, as imported fabrics of Chinese origin and textiles brought in via the Dutch East India Company’s trade were very popular in Japan. At the time of Thunberg’s visit between 1775 and 1776 revealed that some restricted trading had been a reality for nearly 150 years. Those conditions contributed to the development of unique craft traditions for silk and cotton textiles, which were further processed using various advanced techniques to achieve special effects and applications. Thunberg also documented the great significance that those two raw materials held for the people in his account of the country’s Agriculture:

- ‘…the cultivation of Cotton and Silk, is an object of the greatest importance in this country, and furnished the clothing of many millions. For this purpose they cultivate and plant every year the cotton shrub (Gossypium herbaceum), which yields a very fine and white cotton, fit for cloths, wadding, and other uses. The cultivation of Silk depends upon the planting and propagation of the Mulberry-tree, by means of which an incredible number of Silk-worms are bred, and the raw silk produced, of which are made silken stuffs, thread, wadding, and a great many more articles, both of ornament and use.’

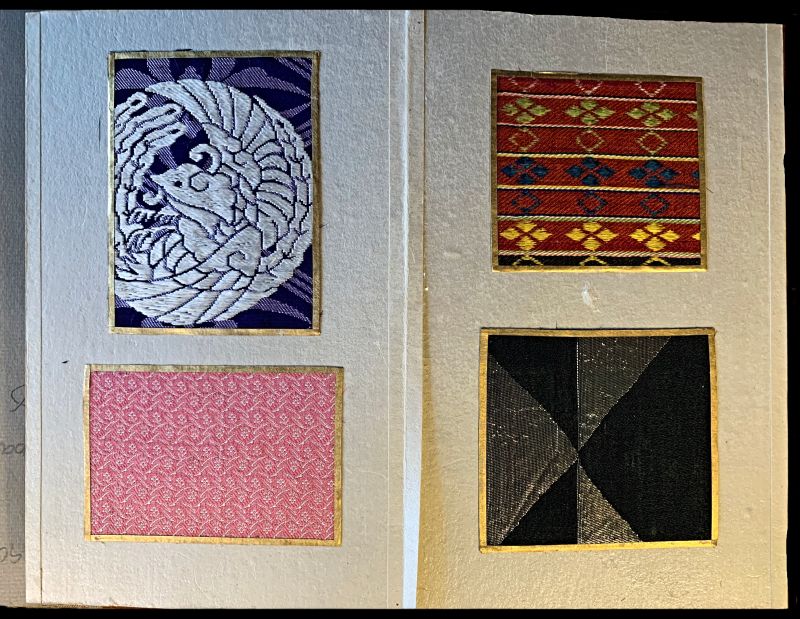

The second Japanese sample catalogue offers further insight and admiration for this skilled textile craft. It contains 85 Japanese samples spread over 30 pages: ’Samples of silk brocade in various colours and motifs edged with narrow stripes of gold paper.’ Additionally, it was fashioned into an advanced bookbixxxnding shaped like a concertina, dating from the 1870s-1880s. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. (The Library. Sample Book: I5654 Ø08). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

The second Japanese sample catalogue offers further insight and admiration for this skilled textile craft. It contains 85 Japanese samples spread over 30 pages: ’Samples of silk brocade in various colours and motifs edged with narrow stripes of gold paper.’ Additionally, it was fashioned into an advanced bookbixxxnding shaped like a concertina, dating from the 1870s-1880s. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. (The Library. Sample Book: I5654 Ø08). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.Like the first sample book studied, this book includes very delicate silk qualities and brocades, many with added gold-patterned weft threads. It features complex weaving techniques, with two or three layers of simultaneously woven motifs or monochrome figured silks with satin, plain weave, gauze, or twill grounds. Some samples also incorporate flat stripes of gold leaf in the patterns on a black background. A thinner gold thread was used for the patterned weft threads on other fabrics. Each fabric sample includes one or several of these featured patterns.

- Ornamental

- Small-patterned

- Figures and landscapes

- Flower designs

- Repetition of motifs

Unlike the first examined sample catalogue, it is impossible to see the selvedges in this book because the edges of the samples are covered with a thin gold frame. This creates some uncertainty about whether they were produced on a traditional handloom or jacquard loom. A few samples are also quite garish in colour, visibly synthetically dyed in pink, purple, etc., suggesting that these were woven after 1876.

Interestingly, the publication describing Japanese textiles at the Victoria and Albert Museum also emphasises that five Japanese weavers travelled to France in 1872, visiting the silk weaving centre of Lyon. The newly acquired experiences resulted in: ‘The jacquard loom they brought back to Japan revolutionised Nishijin weaving practices. Chemical dyes were introduced and, in 1876, a series of Western books on spinning, weaving, and dyeing were translated into Japanese’ (Jackson 2000, quote p. 10). This indicates that an exchange of knowledge in both directions was established between the longstanding silk traditions in both Japan and France.

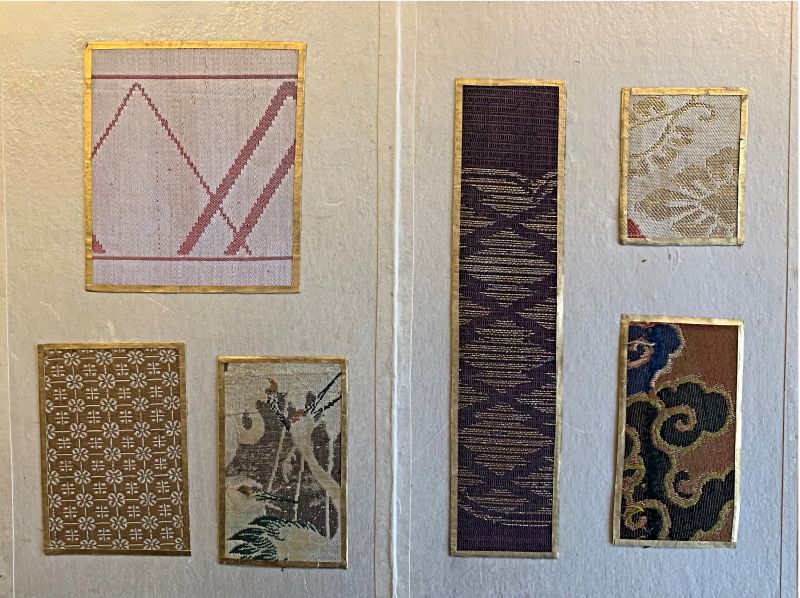

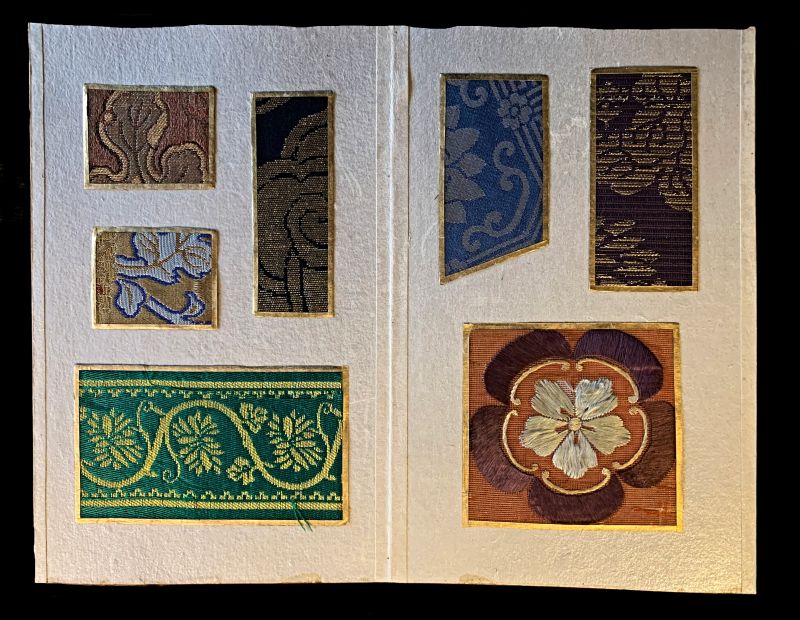

Below are three double pages from this fascinating sample catalogue, illustrating the multifaceted possibilities of pattern combinations in these complex Japanese silk fabrics.

(Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. | The Library. Sample Book: I5654 Ø08). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

(Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. | The Library. Sample Book: I5654 Ø08). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. | The Library. Sample Book: I5654 Ø08). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

(Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. | The Library. Sample Book: I5654 Ø08). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Among the woven samples, the ribbed silk in the right-hand corner also features silk embroidery in the shape of a flower, dominated by flat, long stitches that create a shiny effect. Overall, various embroidery techniques have a centuries-long history in Japan for decorating garments, much like silk weaving. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. | The Library. Sample Book: I5654 Ø08). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Among the woven samples, the ribbed silk in the right-hand corner also features silk embroidery in the shape of a flower, dominated by flat, long stitches that create a shiny effect. Overall, various embroidery techniques have a centuries-long history in Japan for decorating garments, much like silk weaving. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. | The Library. Sample Book: I5654 Ø08). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. The sample book also features this Japanese house and garden motif with water, rendered in an extraordinarily fine tapestry technique. It is impossible to count the number of threads per cm without a magnifying glass. During the Edo period, Japanese gardens aimed to evoke the right state of mind for visitors and their owners alike. Everyday life, religion, and symbolism were all deeply intertwined in the carefully arranged small gardens close to the home – including rocks, stepping stones, mosses, plants, and water features. This is also depicted in the tapestry weaving. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. (The Library. Sample Book: I5654 Ø08). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

The sample book also features this Japanese house and garden motif with water, rendered in an extraordinarily fine tapestry technique. It is impossible to count the number of threads per cm without a magnifying glass. During the Edo period, Japanese gardens aimed to evoke the right state of mind for visitors and their owners alike. Everyday life, religion, and symbolism were all deeply intertwined in the carefully arranged small gardens close to the home – including rocks, stepping stones, mosses, plants, and water features. This is also depicted in the tapestry weaving. (Collection: Design Museum Denmark, København. (The Library. Sample Book: I5654 Ø08). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.After researching these samples and reading about Japanese textile traditions, the most likely explanation for why these two exclusively bound Japanese catalogues with silk samples glued onto the finest Japanese paper – clearly designed to be viewed – ended up in Europe is that they were originally part of an exhibition or fair. International exhibitions were frequently held in European cities during the 1870s, such as København (Copenhagen), Paris, Lyon, and London, and more so in the following decade, when even more events took place. For example, the Second Scandinavian Exhibition of Arts and Industry in København in 1872, the Exposition Universelle et Internationale of 1872 in Lyon, the London International Exhibition of 1874, and the Exposition Universelle of 1878 in Paris. The current owner – the Design Museum in Denmark – was established a few years later, in 1890. However, it is not known exactly when these Japanese catalogues were incorporated into their collection, at least prior to 1948, when one sample was recorded as missing.

This Essay is part of a two-episode series. Explore the Visual Story here…

The visual story (iExposure) includes all samples from these two Japanese sample books, along with interior and exterior images from the Design Museum Denmark, as well as similar examples of such Japanese samples and textiles from the period.

The visual story (iExposure) includes all samples from these two Japanese sample books, along with interior and exterior images from the Design Museum Denmark, as well as similar examples of such Japanese samples and textiles from the period. Sources:

- Cock-Clausen, Ingeborg, Tekstilprøver fra danske arkiver og museer 1750-1975, København 1987.

- Denney, Joyce, ‘Japan and the Textile Trade in Context’, Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade; 1500-1800, pp. 56-65, New York 2013.

- Design Museum Denmark, København. (The Library. Japanese Textile Sample Books: I19072 Ø004 & I5654 Ø08). Research visit, November 2025.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (Chapter of Carl Peter Thunberg, pp. 253-282).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilis Essays, ‘Japanese Textiles in the 1770s – Collections amassed by Carl Peter Thunberg’ (No: CCXIV | January 19, 2026).

- Hareven, Tamara K., The Silk Weavers of Kyoto: Family and Work in a Changing Traditional Industry, California, 2002.

- Jackson, Anna, Japanese Textiles in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2000.

- Miller, Lesley Ellis, Lafuente, Ana Cabrera & Allen-Johnstone Claire, Ed., Silk: Fibre, Fabric and Fashion, V&A, London 2021.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

- Wikipedia (Search term: ‘List of world's fairs’).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE