ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

JAPANESE TEXTILES IN THE 1770s

– Collections amassed by the Naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg

He had the fortune to live to old age, made a nine-year-long journey during the 1770s, amassed extensive natural history and ethnographic collections, and published numerous books and prints. Due to these circumstances, Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) has become one of the most well-known apostles of Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). This essay aims to offer further thoughts on textiles, connected to Thunberg, and to add details from my previous in-depth research on an 18th-century global naturalist network. Silk weaving, the manufacture of paper cloth, and traditional Japanese clothing reflect the time period in both image and text. Together with a brief account of the long journey, which will not only enlighten his mission in natural history but also give insights into his interest in textile traditions and gift exchange from a European perspective, seen in the context of their time.

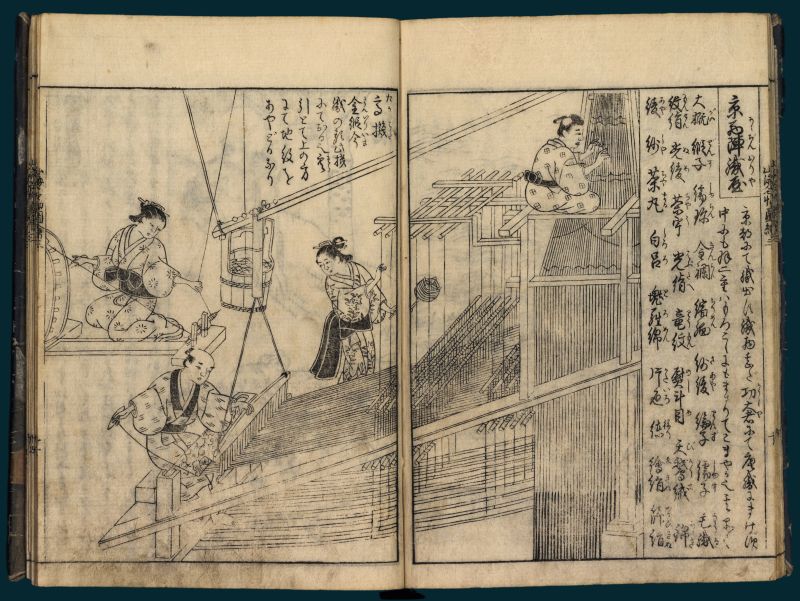

The uniquely preserved five books named ‘Nihon sank meibutsu zue’, numbered 1 to 5, illustrate Japanese local life and craftsmanship in the 18th century. Bound volumes, which, according to the catalogue information from Uppsala University Library, were probably brought to Sweden by Carl Peter Thunberg in 1776, when he left Japan after about 15 months in the country. For this essay, three images related to the production of fabric have been chosen to exemplify the cultural contexts and the exchange of goods from a textile perspective in Japan. In volume three, this illustration demonstrates the weaving of complex motif-woven silk fabric on a draw loom. The male weaver used the shuttle and chose the shedding order from the ten treadles with his bare feet, whilst the assistant on top of the draw loom simultaneously drew the correct warp threads for the desired design. The other two individuals showed the stages of preparing and winding the weft threads onto bobbins. | Artist and engraver: Mitsunobu Hasegawa (1721-1755) from Osaka. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library. Alvin-record: 91777).

The uniquely preserved five books named ‘Nihon sank meibutsu zue’, numbered 1 to 5, illustrate Japanese local life and craftsmanship in the 18th century. Bound volumes, which, according to the catalogue information from Uppsala University Library, were probably brought to Sweden by Carl Peter Thunberg in 1776, when he left Japan after about 15 months in the country. For this essay, three images related to the production of fabric have been chosen to exemplify the cultural contexts and the exchange of goods from a textile perspective in Japan. In volume three, this illustration demonstrates the weaving of complex motif-woven silk fabric on a draw loom. The male weaver used the shuttle and chose the shedding order from the ten treadles with his bare feet, whilst the assistant on top of the draw loom simultaneously drew the correct warp threads for the desired design. The other two individuals showed the stages of preparing and winding the weft threads onto bobbins. | Artist and engraver: Mitsunobu Hasegawa (1721-1755) from Osaka. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library. Alvin-record: 91777).Carl Peter Thunberg’s lengthy journey, which started in August 1770 and was not to be concluded until March 1779, had initially been possible with the bursary he had been granted and a recommendation from Carl Linnaeus. He travelled from Uppsala via Helsingborg and København to Amsterdam, where he remained for more than a month. Thunberg was invited to examine and catalogue plants for the botanist Johannes Burman (1707-1780) and his son Nicolaas Laurens Burman (1734-1793), who realised that the Swede was a capable botanist and found him well qualified and, with his knowledge, able to contribute to a lengthy botanical voyage on one of the Dutch East Indiamen. Thunberg accepted an offer after his return from a good seven-month stay in Paris, and it was decided that his botanical voyage and work as a surgeon for the Dutch East India Company should go to Japan, an area largely unexplored from a European perspective. The conditions prevailing at the time forced him to present himself as a Dutchman, and no other Europeans were allowed to visit Japan. The Dutch language was, therefore, something Thunberg had to learn, and it was for that reason considered suitable for him first to spend some years in the Dutch colony in the Cape Province. In January 1772, the ship set sail for the Cape and arrived three and a half months later. Thunberg was to spend all three years there, making long excursions and discovering new botanical and zoological rarities.

In March 1775, the voyage continued from the Cape towards Japan, with a month-long stay in the Dutch maritime trading centre of Batavia, and the group arrived in Nagasaki in August. As a foreign visitor in the area, he had to follow regulations, which meant that for the first six months, he was only allowed entry into a limited part of the Nagasaki harbour; only after that was he able to botanise in the town. The following year, he had the unique opportunity to visit Tokyo, a journey that took nearly four months in a palanquin, offering the botanist the best possible chance to enhance his knowledge as well as his collections of the flora of Japan. Once he arrived in the city, he could immerse himself further in Japanese culture and meet people who learned about medicine and natural history.

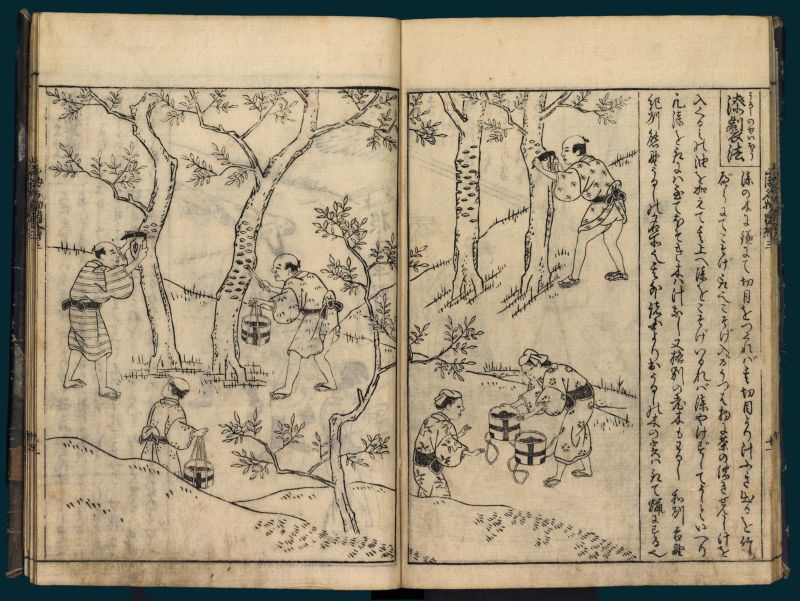

A second example from the same volume of the Japanese book set, this plate was titled ‘Collecting of varnish’. Among other uses in the country, this varnish could be applied to the surface of the paper fabric (see the two images below). Fabrics treated with wax, varnish, or oil served dual purposes. Firstly, it made the material water-repellent, and secondly, it meant that colours of poor fastness could last better if the surface were varnished. | Artist and engraver: Mitsunobu Hasegawa (1721-1755) from Osaka. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library. Alvin-record: 91808).

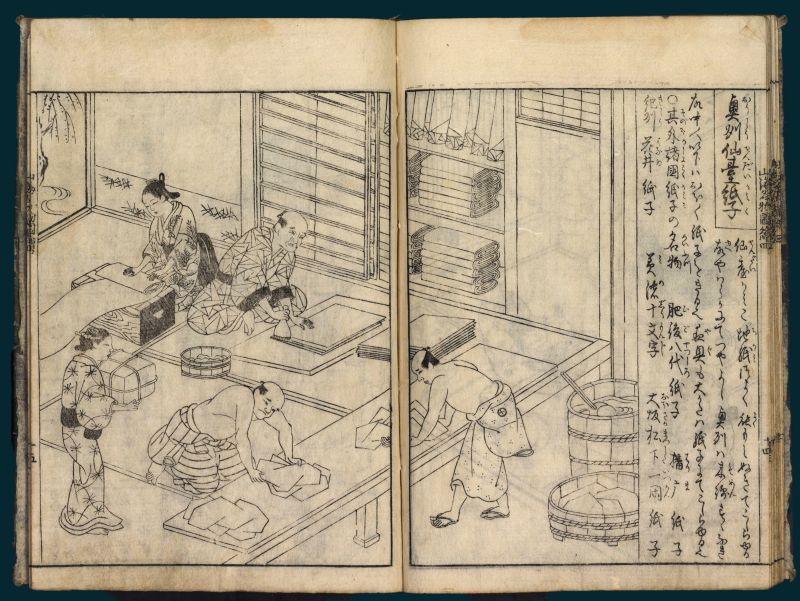

A second example from the same volume of the Japanese book set, this plate was titled ‘Collecting of varnish’. Among other uses in the country, this varnish could be applied to the surface of the paper fabric (see the two images below). Fabrics treated with wax, varnish, or oil served dual purposes. Firstly, it made the material water-repellent, and secondly, it meant that colours of poor fastness could last better if the surface were varnished. | Artist and engraver: Mitsunobu Hasegawa (1721-1755) from Osaka. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library. Alvin-record: 91808). In the fourth volume of the same book set, this ‘Paper cloth from Sendai’ is one of sixteen plates. This most detailed and informative image showed the manufacturing of paper fabric in a workshop, with two female and three male workers. The final product was carefully folded into bundles and placed in a cupboard with sliding doors or packed into parcels for the best protection. Carl Peter Thunberg mentioned the preparation and use of paper fabric in his journal. About the Japanese dress, interestingly, he included this observation in the summer of 1776: ‘Sometimes, but merely as a matter of curiosity, the Japanese make of the bark of the Morus papyrifera, a kind of cloth, which is either manufactured like paper or else spun and woven. The latter sort, quite white, fine, and resembling cotton, is sometimes used by women. The former, printed with flowers, is used for the long nightgowns by elderly people only and is worn by them at no other time than in the winter, when they perspire but little, and then with a gown or two besides.’| Artist and engraver: Mitsunobu Hasegawa (1721-1755) from Osaka. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library. Alvin-record: 91839).

In the fourth volume of the same book set, this ‘Paper cloth from Sendai’ is one of sixteen plates. This most detailed and informative image showed the manufacturing of paper fabric in a workshop, with two female and three male workers. The final product was carefully folded into bundles and placed in a cupboard with sliding doors or packed into parcels for the best protection. Carl Peter Thunberg mentioned the preparation and use of paper fabric in his journal. About the Japanese dress, interestingly, he included this observation in the summer of 1776: ‘Sometimes, but merely as a matter of curiosity, the Japanese make of the bark of the Morus papyrifera, a kind of cloth, which is either manufactured like paper or else spun and woven. The latter sort, quite white, fine, and resembling cotton, is sometimes used by women. The former, printed with flowers, is used for the long nightgowns by elderly people only and is worn by them at no other time than in the winter, when they perspire but little, and then with a gown or two besides.’| Artist and engraver: Mitsunobu Hasegawa (1721-1755) from Osaka. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library. Alvin-record: 91839).![Two such original block-prints on Kozu fibres (Broussonetia papyrifera [syn.] Morus papyrifera) used for clothing, etc., were evidently brought back to Europe by Thunberg from his sojourn in Japan in the years 1775-1776, and are now preserved at the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm. This illustrated paper cloth is one of these papers. (Collection: Etnografiska museet, Stockholm…no. 1874.01.0062). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/4-a-thunberg-japan-800x534.jpg) Two such original block-prints on Kozu fibres (Broussonetia papyrifera [syn.] Morus papyrifera) used for clothing, etc., were evidently brought back to Europe by Thunberg from his sojourn in Japan in the years 1775-1776, and are now preserved at the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm. This illustrated paper cloth is one of these papers. (Collection: Etnografiska museet, Stockholm…no. 1874.01.0062). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Two such original block-prints on Kozu fibres (Broussonetia papyrifera [syn.] Morus papyrifera) used for clothing, etc., were evidently brought back to Europe by Thunberg from his sojourn in Japan in the years 1775-1776, and are now preserved at the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm. This illustrated paper cloth is one of these papers. (Collection: Etnografiska museet, Stockholm…no. 1874.01.0062). Photo: The IK Foundation, London. Altogether, Thunberg’s Ethnographic Collection displays some valuable historically interesting textile objects from 18th century Japan, today administered by the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm, with over 100 items brought back from Japan, 28 of them containing textile materials, anything from complete garments of printed silks to components such as a silk-wrapped shaft of a pipe. The complete list of the unique artefacts is listed in my monograph Textilia Linnaeana… (2017, pp. 281-83) with a brief description to demonstrate Thunberg’s idea of collecting multifarious objects, an idea probably based on wishing to present the variety and versatility of the workmanship and areas of usage of the Japanese textiles, compared to contemporary European traditions.

One further object from Thunberg’s Japanese Ethnographic Collection is this well-preserved toothpick cover in the shape of a Geisha. This close-up detail demonstrates the style of her clothing and reveals a wide selection of Japanese textile materials used for this exquisite object. A quote in translation from the museum catalogue card gives this information: “… several different silks: woven designs with gilded paper strips, velvet, checked plain weave. Face of painted and waxed paper and hair decoration of cut, painted paper…”. This is one of three similarly worked toothpick covers in the collection. (Courtesy: Etnografiska museet, Stockholm… no. 1874.01.0069).

One further object from Thunberg’s Japanese Ethnographic Collection is this well-preserved toothpick cover in the shape of a Geisha. This close-up detail demonstrates the style of her clothing and reveals a wide selection of Japanese textile materials used for this exquisite object. A quote in translation from the museum catalogue card gives this information: “… several different silks: woven designs with gilded paper strips, velvet, checked plain weave. Face of painted and waxed paper and hair decoration of cut, painted paper…”. This is one of three similarly worked toothpick covers in the collection. (Courtesy: Etnografiska museet, Stockholm… no. 1874.01.0069).Carl Peter Thunberg’s visit to Japan was recorded in his journal and other writings as a combination of scientific knowledge intertwined with his admiration and interest in highly developed craft skills, trade patterns, gift exchange, and the importance of diplomacy. His favourable position in the country overall was closely linked to the Dutch ambassador. Like comfortable living conditions, food and drink of the best standard, musical entertainment, receiving textile gifts such as Japanese silk gowns, learning about suitable or unsuitable clothing in various settings, and being part of the highest wealth displays at the time in Japan. The most significant local contacts were the Japanese interpreters. Thunberg gave one of several accounts of these learned men in his journal while staying at the Dutch trading post of Dezima in early November 1775. ‘At the same time, I procured by degrees, some information concerning their government, religion, language, manners, domestic and rural œconomy, &c. I also received from them several books and curiosities of various kinds, the greatest part of which I wished to be able to carry with me to Europe.’ Even if some restrictions existed on the export of books from Japan at the time, the mentioned books might have included the illustrated volumes examined more closely in this essay – books that were probably transported to Sweden in one of his consignments. The logistics during this long-distance voyage over nine years were a complex matter for him, just as for every naturalist on similar journeys. Thunberg recorded these obstacles and possibilities himself in his travel journal at various points during the voyage and explained how best to send collections in contemporary correspondence.

In November 1776, the voyage turned towards Europe again. Still, before that, Thunberg took a six-month break in Java and then an equally long one in Ceylon [Sri Lanka], which provided him with unique opportunities for fresh natural history observations. After a brief stopover in the Cape, the voyage continued in May 1778 to Holland. Once he had arrived in Amsterdam, Thunberg did not travel to Sweden straight away, but to London first, where he visited Joseph Banks (1743-1820), Daniel Solander (1733-1782), Jonas Dryander (1748-1810) and other influential persons in the capital keen to meet the widely-travelled Thunberg. At the same time, he grasped the opportunity to study the great botanical attractions, such as Kew Gardens, Chelsea Physic Garden, the British Museum, and Banks’ impressive collections. The homeward journey again went via Holland and Germany, and in March 1779, Thunberg returned to his homeland, Sweden. The journey, totalling nine years, was to be the longest that any of the Linnaeus Apostles undertook.

Sources:

- Etnografiska museet, Stockholm, Sweden (Museum of Ethnography); the Ethnographical Collection of Carl Peter Thunberg.

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Vol. Six. Carl Peter Thunberg’s travel journal).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (Chapter of Carl Peter Thunberg, pp. 253-282).

- Iwao, S. ‘C.P., Thunbergs ställning i japansk kulturhistoria.’ Svenska Linnésällskapets Årsskrift 1953, pp. 135-147.

- Nordenstam, Bertil, ed., Carl Peter Thunberg – Linnean, resenär, naturforskare 1743-1828, Stockholm 1993.

- Rookmakker, L. C., and Svanberg, Ingvar. ‘Bibliography of Carl Peter Thunberg’, Svenska Linnésällskapets Årsskrift 1992-1993, pp. 7-72.

- Skuncke, Marie-Christine, Carl Peter Thunberg: Botanist and Physician, Uppsala 2014.

- Svedelius, Nils, ‘Carl Peter Thunberg 1743-1828. Ett tvåhundraårsminne ’, Svenska Linnésällskapets Årsskrift 1944, pp 29-64.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Tal om Japanska Nationen, hållet för Kongl. Vetensk. Acad. Praesidii Tal i Kongl. Vetenskapsakademien, 1784.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

- Uppsala University Library, Sweden; Three images from the Japanese book ‘Nihon sank meibutsu zue’, Volumes 3 & 4 (Digital sources: Alvin).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE