ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

LINEN BLEACHING GROUNDS

– A Case Study of Household Linen and Laundry: 1530s to 1940s

The bleaching of linen by Haarlem manufacturers in Holland, centres that treated large consignments, can be studied through several paintings and engravings from the 17th century. Still, evidence of this same tradition within individual households or villages is visible both before and after this period through artworks and photographs. This 400-year visual record will depict such local communities – in the German lands, Holland, Great Britain, Denmark, and Sweden – concentrating on domestic linen and the families involved in this work. These images reveal surprisingly many details of freshly woven lengths of linen, ready-made garments, bed linen, and offer insight into women’s work in particular. Good weather during summer was vital for successful bleaching, as it also allowed the laundry to dry. Green fields, meadows, or sandy beaches, whether in urban or rural areas, were preferred locations. However, field bleaching of linen was a slow process spanning several months, so by the late 18th century, new chemical methods were developed to whiten linen – often involving hazardous treatments for textiles and the environment.

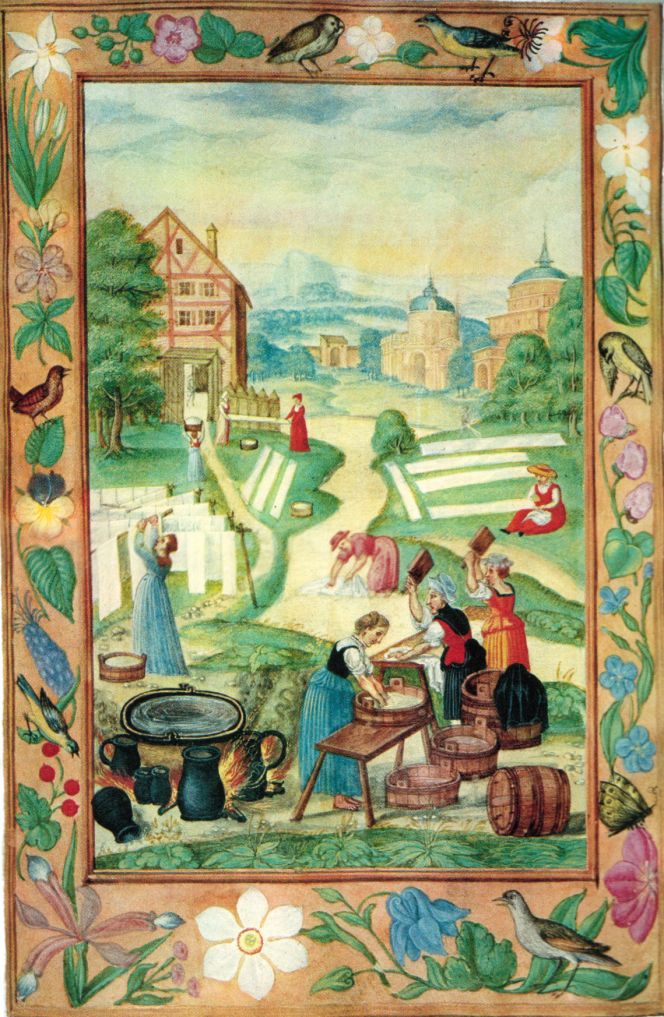

‘The great washday’ from the alchemical handbook ‘Splendor Solis’, first published in Nürnberg in 1531, is a highly illustrative hand-coloured depiction. It shows a group of women working with laundry and linen bleaching. Even if not visible in the picture, access to water was essential, like from a river or lake; alternatively, rainwater could be collected in barrels. Water was boiled in a large outdoor iron or copper pan, wooden tubs were used for soaking linen, and two women vigorously beat the laundry with washing bats. The long, narrow linen sheets dry on wooden frames, while some linen is placed on the ground for bleaching. Notice the importance of guarding the linen – by the sitting lady – due to potential pigs running loose, small children playing, or theft of the valuable fabric. Uncertainty remains about the exact location of this community; it is believed to be near Augsburg in present-day southern Germany. The German lands, like northern France, the Low Countries, and several other European regions, gradually developed into significant flax-producing areas during the late Medieval period. (Image: Wikimedia).

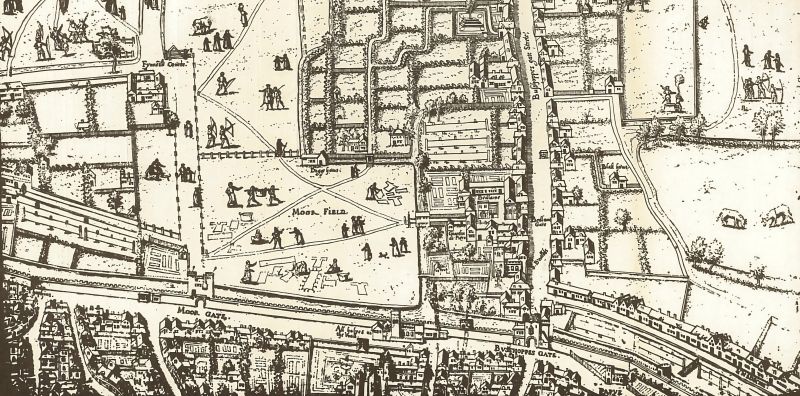

‘The great washday’ from the alchemical handbook ‘Splendor Solis’, first published in Nürnberg in 1531, is a highly illustrative hand-coloured depiction. It shows a group of women working with laundry and linen bleaching. Even if not visible in the picture, access to water was essential, like from a river or lake; alternatively, rainwater could be collected in barrels. Water was boiled in a large outdoor iron or copper pan, wooden tubs were used for soaking linen, and two women vigorously beat the laundry with washing bats. The long, narrow linen sheets dry on wooden frames, while some linen is placed on the ground for bleaching. Notice the importance of guarding the linen – by the sitting lady – due to potential pigs running loose, small children playing, or theft of the valuable fabric. Uncertainty remains about the exact location of this community; it is believed to be near Augsburg in present-day southern Germany. The German lands, like northern France, the Low Countries, and several other European regions, gradually developed into significant flax-producing areas during the late Medieval period. (Image: Wikimedia). This bird’s-eye view of the Moor Field area in London around 1575 offers a brief glimpse into several stages of caring for household linen. The field was located just north of the city and provided women from nearby quarters, or their hired laundresses, with an opportunity to dry and bleach laundry — including long linen shirts and various lengths of sheets, which are clearly visible. Interestingly, the importance of guarding the linen was marked by women sitting on the ground near their belongings, similar to the earlier image depicted above. Additionally, one long linen sheet appears to be fastened to hooks on the ground, possibly as a method to place valuable fabrics during drying or bleaching. Alternatively, these hooks may have been used as wringers to squeeze water out of the laundry. It is also worth noting that all handwoven linen from this period and the following centuries was initially unbleached, that is, in its original greyish-brown flax fibre colour. After each wash, the linen sheets and garments gradually became whiter over time. (Detail of plate from a map of London. Image: Wikimedia).

This bird’s-eye view of the Moor Field area in London around 1575 offers a brief glimpse into several stages of caring for household linen. The field was located just north of the city and provided women from nearby quarters, or their hired laundresses, with an opportunity to dry and bleach laundry — including long linen shirts and various lengths of sheets, which are clearly visible. Interestingly, the importance of guarding the linen was marked by women sitting on the ground near their belongings, similar to the earlier image depicted above. Additionally, one long linen sheet appears to be fastened to hooks on the ground, possibly as a method to place valuable fabrics during drying or bleaching. Alternatively, these hooks may have been used as wringers to squeeze water out of the laundry. It is also worth noting that all handwoven linen from this period and the following centuries was initially unbleached, that is, in its original greyish-brown flax fibre colour. After each wash, the linen sheets and garments gradually became whiter over time. (Detail of plate from a map of London. Image: Wikimedia). An etching of ’s-Hertogenbosch in the present-day Netherlands, dated circa 1609, shows bleaching and drying of linen clearly visible in several enclosed green fields. All these parcels of land were situated close to the walled town, possibly connected via a wooden bridge on the opposite side of the river. Cattle and dogs are fenced out to ensure that shirts and bed linens are not trampled. Judging by the long, narrow linen sheets for bleaching in some of the enclosures, it is even likely that linen was produced nearby and required bleaching grounds for their manufacturing process. Furthermore, this town was only about 100 kilometres from Haarlem, the centre of linen manufacturing, which was the most successful in this trade during the first half of the 17th century. s-Hertogenbosch was evidently part of the same extensive linen production area. (Collection: The British Library, London, UK. Etching by Cornelius Claesz, Amsterdam, part of George III’s Topographic Collection. No. BLL01004806016)

An etching of ’s-Hertogenbosch in the present-day Netherlands, dated circa 1609, shows bleaching and drying of linen clearly visible in several enclosed green fields. All these parcels of land were situated close to the walled town, possibly connected via a wooden bridge on the opposite side of the river. Cattle and dogs are fenced out to ensure that shirts and bed linens are not trampled. Judging by the long, narrow linen sheets for bleaching in some of the enclosures, it is even likely that linen was produced nearby and required bleaching grounds for their manufacturing process. Furthermore, this town was only about 100 kilometres from Haarlem, the centre of linen manufacturing, which was the most successful in this trade during the first half of the 17th century. s-Hertogenbosch was evidently part of the same extensive linen production area. (Collection: The British Library, London, UK. Etching by Cornelius Claesz, Amsterdam, part of George III’s Topographic Collection. No. BLL01004806016) Interestingly, several of the naturalist Carl Linnaeus’ long-distance travelling apostles from the period 1740s to 1790s mentioned the brown holland or linen of various qualities: Pehr Kalm, for instance, bought ‘brown holland for 4 Shirts with cuffs’ upon his arrival in England in 1748, while Göran Rothman’s estate inventory of 1779 listed ‘3 shirts of fine holland, 4 ditto of coarser brown holland, 10 ditto with cuffs, 6 ditto ready cut’. The detailed labelling ‘brown holland’ indicated an unbleached linen quality, which became whiter after many washes and bleaching attempts. This oil on canvas by Jacob van Ruisdael shows the extensive bleaching grounds in Haarlem, Holland, in the previous century, dating circa 1665, as noted earlier in a place where the bleaching of linen was processed on an “industrial scale” in the 17th century. The Swedish Linen Manufacture of Flor in the province of Helsingland, which Linnaeus himself visited in 1732, also carried out linen bleaching on a smaller scale using similar methods. (Collection: Kunsthaus, Zürich, Switzerland).

Interestingly, several of the naturalist Carl Linnaeus’ long-distance travelling apostles from the period 1740s to 1790s mentioned the brown holland or linen of various qualities: Pehr Kalm, for instance, bought ‘brown holland for 4 Shirts with cuffs’ upon his arrival in England in 1748, while Göran Rothman’s estate inventory of 1779 listed ‘3 shirts of fine holland, 4 ditto of coarser brown holland, 10 ditto with cuffs, 6 ditto ready cut’. The detailed labelling ‘brown holland’ indicated an unbleached linen quality, which became whiter after many washes and bleaching attempts. This oil on canvas by Jacob van Ruisdael shows the extensive bleaching grounds in Haarlem, Holland, in the previous century, dating circa 1665, as noted earlier in a place where the bleaching of linen was processed on an “industrial scale” in the 17th century. The Swedish Linen Manufacture of Flor in the province of Helsingland, which Linnaeus himself visited in 1732, also carried out linen bleaching on a smaller scale using similar methods. (Collection: Kunsthaus, Zürich, Switzerland). Some general observations on laundry during the 18th and 19th centuries offer further insights into the various needs for drying and bleaching linen. Even for women who were not professional washerwomen or laundresses, the washing day would be a time-consuming and physically demanding part of household chores, involving soaking, scrubbing, wringing, and rinsing. For instance, Monday was the traditional washing day in England, with clothes that would already have been soaked on Saturday evening and subsequent tasks, including drying and ironing, completed on Tuesday or Wednesday. However, this was unlikely to occur every week, more probably every fortnight or once a month, and in winter, less frequently. The size of the household naturally played a vital role in determining how often laundry was done and how long it took, considering all the necessary steps involved. The housewife might do the washing herself, though if the household employed servants, they would certainly assist. A household with many servants might employ its own full-time washerwoman, hire a washerwoman to come in, or send the laundry out to a washerwoman or laundry. In the 18th century, when most clothing was made of linen, silk, or wool, it was washed less frequently. Wool was usually beaten or brushed clean and was rarely washed, and this practice continued throughout the period. Linen would be soaked in lye – a solution of fine white ash from the hearth – to remove stains, but if soap was used, the dirty clothes had to be boiled. Often, silk could not be washed at all and would need to be brushed clean, if possible. However, during the 19th century, white ash became scarce, and various kinds of soap were widely introduced to remove stains. While soap had been available for a long time, it was expensive for ordinary people.

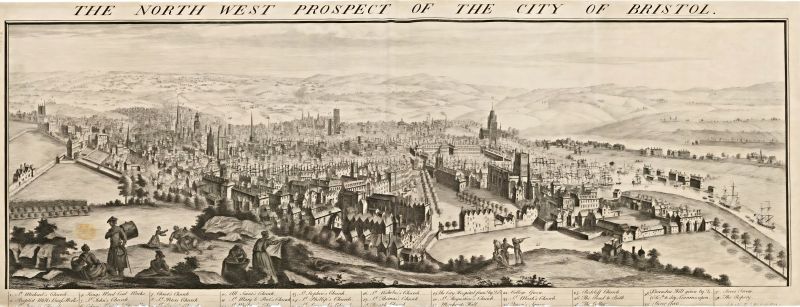

‘The South East Prospect of the City of Bristol’, published in 1734. This depiction is particularly enlightening from the perspective of the increasing industrialisation, contrasted with the need to dry and bleach the laundered linen outdoors. The women had chosen green fields and hedges as far away from the coal chimney smoke as possible – in the high-level countryside on the opposite side of the city. In contrast, the intense coal burning in densely populated areas quickly made the laundry black-dotted. | Etching by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck. (Collection: The British Library, London, UK. Maps K.Top. 37.37b Public Domain).

‘The South East Prospect of the City of Bristol’, published in 1734. This depiction is particularly enlightening from the perspective of the increasing industrialisation, contrasted with the need to dry and bleach the laundered linen outdoors. The women had chosen green fields and hedges as far away from the coal chimney smoke as possible – in the high-level countryside on the opposite side of the city. In contrast, the intense coal burning in densely populated areas quickly made the laundry black-dotted. | Etching by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck. (Collection: The British Library, London, UK. Maps K.Top. 37.37b Public Domain).The long linen sheets – about 50-70 cm wide – seen in several of the adjoining images above were narrow due to the limited hand-loom widths before industrialisation. After being removed from the loom, the unbleached linen, woven in domestic households or factories, had to be washed in various alkalis or acids, such as potash, pearl ash, soda, salt, sour milk, soap, or diluted sulphuric acid, to speed up the bleaching process. As shown, the linen sheets were laid out flat on a green field or other suitable ground, preferably in sunshine, so that the fabric could be bleached to the desired level of whiteness over time. However, a major change was approaching, as summarised by L. Gittins: ’In the course of the eighteenth century textile bleaching was transformed from a medieval craft to an efficient chemical process that was still in use in the early years of the twentieth century’ (p. 194). This shift occurred in stages, notably after the invention of bleaching powder based on chlorine in the 1790s, which was adopted by some manufacturers, while others continued with older methods. Further reasons for these changes included the growing size of towns and cities. Additionally, in the 19th century, more people moved to urban areas, which led to the disappearance of nearby green fields and meadows suitable for bleaching.

‘A View towards the Swedish Coast from the Ramparts of Kronborg Castle’. Oil on canvas by C.W. Eckersberg (1783-1853). A backdrop to this military exercise is the two women taking care of laundry to the left in the picture – with their field drying and bleaching linen and, by now, most probably also the increasingly popular white cotton. Notice how the washing was placed in a direct southerly spot to take advantage of as many hours of warm sunshine as possible on a summer day in 1829, close to busy waters in Øresund. (Collection: Statens Museum for Kunst, København, Denmark. No: KMS3241. On display in 2021). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

‘A View towards the Swedish Coast from the Ramparts of Kronborg Castle’. Oil on canvas by C.W. Eckersberg (1783-1853). A backdrop to this military exercise is the two women taking care of laundry to the left in the picture – with their field drying and bleaching linen and, by now, most probably also the increasingly popular white cotton. Notice how the washing was placed in a direct southerly spot to take advantage of as many hours of warm sunshine as possible on a summer day in 1829, close to busy waters in Øresund. (Collection: Statens Museum for Kunst, København, Denmark. No: KMS3241. On display in 2021). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. A second example from the Golden Age of Danish painting is this oil on canvas, titled ’Bleaching Linen in a Clearing’ from 1858, by the landscape painter P.C. Skovgaard (1817-1875). The peaceful impression of a beech forest forms the backdrop to the women’s bleaching of white linen or cotton textiles, which they will carry home in the depicted basket from the sunny forest glade. To compose atmosphere and light in Danish nature was his speciality, and this romantic view of laundry tasks is a masterful depiction of that skill. (Collection: Statens Museum for Kunst, København, Denmark. No: KMS3772. On display in 2021). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

A second example from the Golden Age of Danish painting is this oil on canvas, titled ’Bleaching Linen in a Clearing’ from 1858, by the landscape painter P.C. Skovgaard (1817-1875). The peaceful impression of a beech forest forms the backdrop to the women’s bleaching of white linen or cotton textiles, which they will carry home in the depicted basket from the sunny forest glade. To compose atmosphere and light in Danish nature was his speciality, and this romantic view of laundry tasks is a masterful depiction of that skill. (Collection: Statens Museum for Kunst, København, Denmark. No: KMS3772. On display in 2021). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. From 1890 to 1900, it still appears to have been common practice to lay out linen and cotton household textiles on the ground to dry and bleach. Among other locations, this tradition has been documented via several photographs taken along the Whitby shore in North Yorkshire, where families had such white garments and bedlinen spread out on the sand. It was also crucial to supervise one’s property, as mentioned in earlier periods, to prevent it from being trampled or, worse still, to avoid the risk of theft, since linen textiles were always somewhat valuable. In this particular image, it seems that a group of children is responsible for the whitewashing on the sand. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, UK. Photograph book 3/21, unknown photographer).

From 1890 to 1900, it still appears to have been common practice to lay out linen and cotton household textiles on the ground to dry and bleach. Among other locations, this tradition has been documented via several photographs taken along the Whitby shore in North Yorkshire, where families had such white garments and bedlinen spread out on the sand. It was also crucial to supervise one’s property, as mentioned in earlier periods, to prevent it from being trampled or, worse still, to avoid the risk of theft, since linen textiles were always somewhat valuable. In this particular image, it seems that a group of children is responsible for the whitewashing on the sand. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, UK. Photograph book 3/21, unknown photographer). ‘Women hanging the washing in Arild, Skåne’ in 1936 and ‘A backyard in Stockholm’ with hanging household linen and garments in 1946. A study of hundreds of photographs depicting various stages in the laundry process, mainly dating from the first half of the 20th century, has not revealed any pictures of washings placed on the ground. At this period, washing powders, including various chemical whitening agents, had also made the slower tradition of linen field bleaching cumbersome and unnecessary. It also became harder and harder over time to find a clean spot to dry your laundry on fields and hedges when more and more people moved to towns and cities. Washing lines became favoured or even the only possibility in urban areas. So judging by the significant number of preserved photographs from Swedish cities, from towns and countryside alike, to hanging out the washing like in these two pictures, dating from summers in the 1930s and 1940s, this practise seems to have been the favoured choice, just as it is still today in good weather. (Collection: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. No: NMA.0060833. Photo by Gunnar Lundh in 1936 & No: NMA.0027774. Photo by K.W. Gullers in 1946. DigitaltMuseum).

‘Women hanging the washing in Arild, Skåne’ in 1936 and ‘A backyard in Stockholm’ with hanging household linen and garments in 1946. A study of hundreds of photographs depicting various stages in the laundry process, mainly dating from the first half of the 20th century, has not revealed any pictures of washings placed on the ground. At this period, washing powders, including various chemical whitening agents, had also made the slower tradition of linen field bleaching cumbersome and unnecessary. It also became harder and harder over time to find a clean spot to dry your laundry on fields and hedges when more and more people moved to towns and cities. Washing lines became favoured or even the only possibility in urban areas. So judging by the significant number of preserved photographs from Swedish cities, from towns and countryside alike, to hanging out the washing like in these two pictures, dating from summers in the 1930s and 1940s, this practise seems to have been the favoured choice, just as it is still today in good weather. (Collection: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. No: NMA.0060833. Photo by Gunnar Lundh in 1936 & No: NMA.0027774. Photo by K.W. Gullers in 1946. DigitaltMuseum).Sources:

- Ashelford, Jane, Care of Clothes, National Trust, London 1997 (pp. 6-7).

- DigitaltMuseum, online (Search words: ‘tvätt’, ‘tvätta’, ‘linnetyg’, ‘bleka’, etc. Swedish words, to establish if any photographs include bleaching grounds. The result was negative).

- Geijer, Agnes, Ur Textilkonstens Historia, Stockholm 1994.

- Gittins, L., ‘Innovations in Textile Bleaching in Britain in the Eighteenth Century’, Business History Review, Harvard, Volume 53, Issue 2, Summer 1979, pp. 194-204.

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015 (pp. 297-305).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017.

- Hazelius-Berg, Gunnel, ‘Tvätt’, Fataburen pp. 115-129, 1970.

- Statens Museum for Kunst, København, Denmark. | Visit in 2021.

- Whitby Museum (Whitby Lit. & Phil), Whitby, UK | Library & Archive & Photographic Collection. Research visits from 2006 to 2012.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE