ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

MUSIC, DANCE AND TEXTILES

– Observations by 18th Century Naturalists

Varied textiles such as short jackets, tapestries, blue linen cloth, silk nightgowns, needlework or bark cloths were mentioned in connection to music in journals written by Carl Linnaeus’ seventeen apostles – who travelled to more than fifty countries from 1746 to 1799. This study is based on a selection of primary sources and my earlier research into these textile traditions, foremost giving examples of fabric related to music, musicians, song and dance performances noticed by six of Linnaeus’ former students on their travels. The accounts reflect traditions seen from an 18th century perspective originating in present-day Turkey, France, Japan, China, French Polynesia, Egypt, South Africa and in a coastal area of the South China Sea.

It was quite common among the Swedish naturalists to make negative judgments of experienced music during their travels in Africa, Asia or the Mediterranean area – probably due to that they never had heard music from other cultures than their own before the journeys. The importance of the performers’ dress was also occasionally observed in such accounts. Here introduced with the type of music they may have been acquainted with, via a portrait of the Swedish musician, composer and poet Carl Michael Bellman playing the cittern in 1779. Other music known to them, possibly being vocal and instrumental music in churches or outdoor musical entertainments in parks if visiting London or Paris. Oil on canvas by Per Krafft the Elder. (Courtesy of Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, No: NMGrh 1061. Wikimedia Commons).

It was quite common among the Swedish naturalists to make negative judgments of experienced music during their travels in Africa, Asia or the Mediterranean area – probably due to that they never had heard music from other cultures than their own before the journeys. The importance of the performers’ dress was also occasionally observed in such accounts. Here introduced with the type of music they may have been acquainted with, via a portrait of the Swedish musician, composer and poet Carl Michael Bellman playing the cittern in 1779. Other music known to them, possibly being vocal and instrumental music in churches or outdoor musical entertainments in parks if visiting London or Paris. Oil on canvas by Per Krafft the Elder. (Courtesy of Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, No: NMGrh 1061. Wikimedia Commons).The natural historian Fredrik Hasselquist made one such typical notation in his diary of a condemnable and curious angle alike from Magnesia (Manisa, Turkey) in March 1750:

‘They consisted here, as in other places, in music and dancing, tho’ quite foreign to our taste. The music were two small kettle drums of copper, and a kind of rough and ill-sounding dulcimer. The musicians beat both so hard, that in a very large room, open on all sides, none could hear what another said, tho’ he spoke loud; but there was nothing like order or time kept. The dance was performed by one person, who might justly be said to dance for all. He was dressed in a short jacket, was barefooted, and looked like a Turkish soldier. He held in each hand two wooden spoons. Thus accoutred, he skipped about the middle of the room, and moved his head and arms as much as his feet, at the same time often bending his body backwards, forwards, and sideways. He held the spoons, two in each hand, in such a manner between his fingers, that he could frequently strike them together, which with the rough music made a noise no ways agreeable to our ears.’

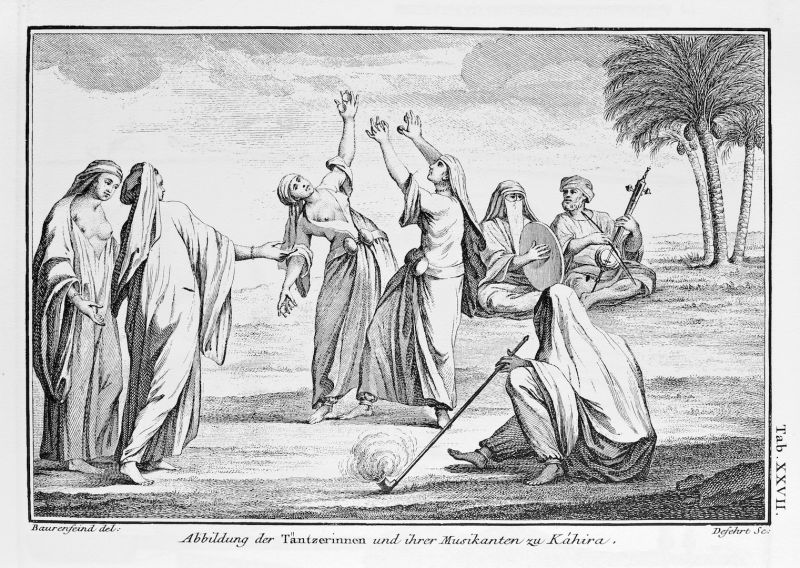

A second example of Fredrik Hasselquist’s observations (June 1750) of women dancers in Egypt, concurs fairly well with this depiction made during another Linnaeus’ apostle, Peter Forsskål’s visit to the region about ten years later by the draftsman of the Royal Danish Exhibition to Arabia. Named: ‘Female dancers and their musicians in Kahira’. Such dancing, the music and the women’s dress were noted by Hasselquist; the costume consisting of blue linen, at times the dancers showed their faces or hiding behind veils as decreed by local custom. (Originally in: Niebuhr, Carsten, Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien…Tab. XXVII).

A second example of Fredrik Hasselquist’s observations (June 1750) of women dancers in Egypt, concurs fairly well with this depiction made during another Linnaeus’ apostle, Peter Forsskål’s visit to the region about ten years later by the draftsman of the Royal Danish Exhibition to Arabia. Named: ‘Female dancers and their musicians in Kahira’. Such dancing, the music and the women’s dress were noted by Hasselquist; the costume consisting of blue linen, at times the dancers showed their faces or hiding behind veils as decreed by local custom. (Originally in: Niebuhr, Carsten, Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien…Tab. XXVII).Whilst Carl Peter Thunberg, during his time in Japan, took the opportunity to watch dancing girls and their clothing, made up of the finest silk nightgowns, at times 30 or even more, one on top of the other. The dancers moved in time to the music, one after the other was removed and left hanging from the waist. He assumed the reason to be as follows in his travel journal (June 1776, Osaka): ‘…the girls growing warm while they are dancing, partly to cool themselves, and partly to make a show of their finery, pulled them off by degrees, one after the other, so that a whole dozen of them together hang down from their girdle, with which they were tied about their bodies, without hindering them in the least in their evolutions’. That event was described once more by the traveller in the chapter on Japanese traditions of festivities and dancing in his extensive journal.

Carl Peter Thunberg’s forth volume of the English edition printed in 1795, furthermore includes this detailed depiction of: ’A Japanese Lady, with her Lute, in her usual dress’. (Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels…1794, vol. four, Plate II).

Carl Peter Thunberg’s forth volume of the English edition printed in 1795, furthermore includes this detailed depiction of: ’A Japanese Lady, with her Lute, in her usual dress’. (Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels…1794, vol. four, Plate II).Additionally, Carl Peter Thunberg observed already in 1771 a textile and music-related tradition during his nine-year-long journey, as the Parisians on 30 May put on annually recurring festivities, called the feast of the sacraments (Fête-Dieu), all churches arranged parades, music, flower arrangements and candles. An important part was that along many streets people hung ‘tapestry of all sorts’ as high up as the second floor. The walls of the houses being decorated with colourful weavings must have formed a part of the spectacle itself, while the owners had the opportunity to show off their textile wealth to neighbours and other passers-by.

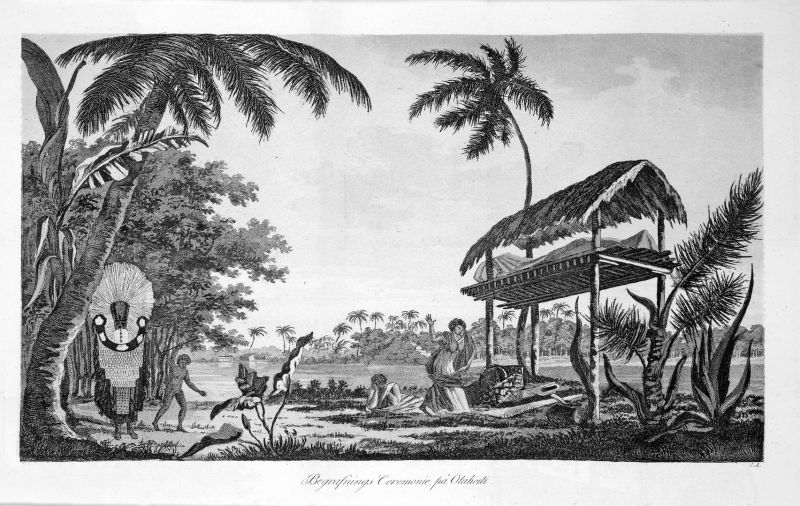

The experience of music and dance on Ulietea (Raiatea) in 1769, is shown here in the artist Sydney Parkinson’s representation from James Cook’s first voyage. This plate is a clear example of the fact that women’s as well as men’s clothing was made from the locally produced bark cloths (illustrated with a touch of “Europeanisation”), put into words in journals by Joseph Banks, James Cook and Sydney Parkinson from the entire Polynesian region – during a journey when the Linnaeus’ apostle Daniel Solander also took part as a botanist. (Originally in: Hawkesworth, John, An Account of the Voyages…, plate VII).

The experience of music and dance on Ulietea (Raiatea) in 1769, is shown here in the artist Sydney Parkinson’s representation from James Cook’s first voyage. This plate is a clear example of the fact that women’s as well as men’s clothing was made from the locally produced bark cloths (illustrated with a touch of “Europeanisation”), put into words in journals by Joseph Banks, James Cook and Sydney Parkinson from the entire Polynesian region – during a journey when the Linnaeus’ apostle Daniel Solander also took part as a botanist. (Originally in: Hawkesworth, John, An Account of the Voyages…, plate VII). During a visit on the close-by island of Tahiti in August 1773, during James Cook’s second voyage, the bark cloth was noticed to be of ceremonial significance as well by the botanist Anders Sparrman in his journal. The travellers became spectators at a dance, regarded as honouring dead relatives, where the dancers wore bark cloths dyed red in the shape of girdles around the waist. Heaps of bark cloth were also on display, later to be distributed to the musicians and dancers. (Sparrman, A., Resa omkring Jordklotet…1802, Pl. XIII).

During a visit on the close-by island of Tahiti in August 1773, during James Cook’s second voyage, the bark cloth was noticed to be of ceremonial significance as well by the botanist Anders Sparrman in his journal. The travellers became spectators at a dance, regarded as honouring dead relatives, where the dancers wore bark cloths dyed red in the shape of girdles around the waist. Heaps of bark cloth were also on display, later to be distributed to the musicians and dancers. (Sparrman, A., Resa omkring Jordklotet…1802, Pl. XIII).Before Anders Sparrman entered Cook’s second voyage as an assisting botanist, he stayed in the Cape region in southernmost Africa. One observation during April 1772 was particularly linked to music and textile work. He met a hospitable, deeply Christian farmer where he noticed with satisfaction from his European perspective that the house shone of both womanly industriousness and religiosity: ‘I found the female slaves singing psalms, while they were at their needlework’.

Whilst approximately two decades earlier, in September 1751, Pehr Osbeck made a description of various Chinese traditions during his time as a priest onboard a Swedish East India Company ship. One such observation included music as well as clothing: ’Plays were acted gratis in the streets. A scaffold is built quite across the streets, here and there, but commonly at the corner houses, from one corner to the other. The scaffold is about six yards above the ground so that anyone may with ease pass under it. It is closely covered with boards, and chairs are placed on it for the actors and musicians. The players generally wear long gowns, and sometimes are dressed like harlequins. The inhabitants are no doubt better pleased with their singing, bawling, and mimicries than the Europeans, who are used to see their own theatrical entertainments much more skilfully conducted.’

Concluding this essay of links between textiles and music as observed by 18th century naturalists – a few years earlier (9 Oct. 1746) as the first of the so-called Linnaeus Apostles – Christopher Tärnström wrote a comparable note in his journal, when the ship anchored close to a coastal area in the South China Sea: ‘Early in the morning these Chinese came on board again, accompanied by the others, bringing us rice, hens, a kind of tobacco, fish etc. and were well paid for it all. An old man, who appeared to be the chief, wore a kind of dressing gown of fine nankeen, was quite content after drinking aquavit, tea and wine with me for a while. And he was very fond of books, singing his strange Chinese chant which was somewhat similar to that of the Russians.’ Via in-depth studies of the travel journals, it has emerged that their attention often had several purposes from a textile as well as musical point of view. In the main as being part of their Instruction or personal aims to collect objects and information – like bark cloths or writing down musical notations – to learn as much as possible about various cultures. Additionally, in the form of curious observations (repeatedly with negative remarks) or just by making a note about the enjoyment of viewing a dance entertainment and beautiful clothing or listening to a ‘soft and delicious song’.

Sources:

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012.

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 193-194, 213, 245, 252, 257 & 277).

- Hawkesworth, John, An Account of the Voyages undertaken by the order of his present Majesty for making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere..., London 1773, vol. 2.

- Niebuhr, Carsten, Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegender Ländern. Volume One, Kopenhagen 1774.

- Sparrman, Anders, Resa omkring Jordklotet, I sällskap med Kapit. J. Cook och Hrr Forster. Åren 1772, 73, 74 och 1775. Förrättad och beskrifwen af Anders Sparrman, Första afdelningen, Stockholm 1802.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779, vol. IV., London 1795.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE