ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

NEEDLEWORK AND SEWING TOOLS

– Traces of Textile Trade in Whitby from the 1840s to 1914

Needlework and sewing by hand required cloth, yarn or threads of linen, cotton, wool or silk, needles, pincushions, frames, thimbles etc. These tools and accessories, as well as the traders involved in directories, census returns, and advertisements in Whitby Gazette, together with relevant objects surviving locally – have been part of my textile research and will be looked at more closely in this essay. Since the written sources related to the 1850s-1914 period and the kept objects in the Social History section of Whitby Museum in the main are Victorian, this is the period about which there is most knowledge of this coastal town in North Yorkshire. Some influences from a broader geographical perspective are also essential to consider for the overall understanding of handicrafts, trade and growing mechanisation.

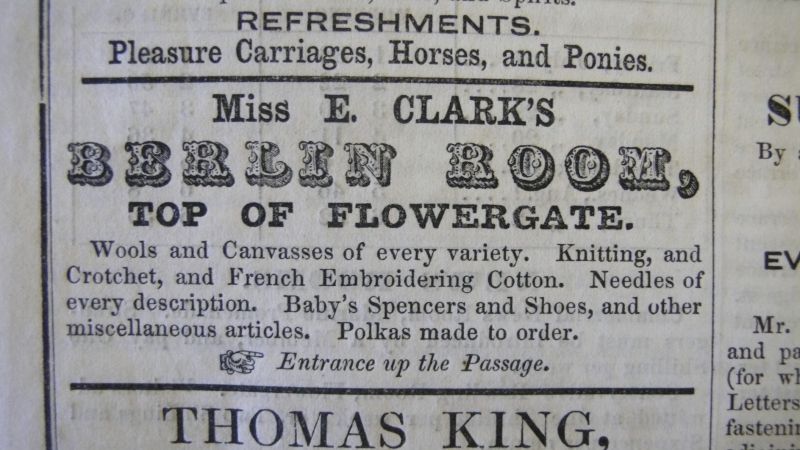

Local inhabitants and visitors could buy embroidery materials at ‘Miss E. Clark’s Berlin Room’. Miss Clark was a frequent advertiser from 1855 to 1864 – this announcement is from 27 July 1855 – and she may already have been active before the founding of the weekly Whitby Gazette. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Gazette). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Local inhabitants and visitors could buy embroidery materials at ‘Miss E. Clark’s Berlin Room’. Miss Clark was a frequent advertiser from 1855 to 1864 – this announcement is from 27 July 1855 – and she may already have been active before the founding of the weekly Whitby Gazette. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Library & Archive, Whitby Gazette). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.In an advertisement of April 1861, the same Miss E. Clark’s Berlin Room also provided ‘Traced muslin for embroidering’ and ‘Berlin, Crochet and Braiding Patterns sold or lent on hire.’ We can also assume that it would have been possible to buy any other requirement for embroidery in her shop. The unmarried Elizabeth Clark is also mentioned in the censuses of 1851 and 1861, aged 46 and 56, as a ‘Berlin Wool dealer’ living in Flowergate.“Clark Elizabeth, Flowergate” is listed as a “Berlin Wool Dealer” in Slater’s Directory of 1864. These various sources are evidence that her shop was in existence at least from 1851 to 1864. In fact, Miss Clark may possibly have worked with an older woman called Elizabeth Wardill, who is listed under the same occupation in the Slater 1864 Directory and the censuses of 1851 and 1861 and is mentioned again at the age of 83 in 1871 as a ‘Retired Berlin Wool dealer’. The 1871 census also lists two other women who worked with Berlin wool: the unmarried 32-year-old Sara Jane Hill and the 49-year-old widow Ann Thirkell, who owned a ‘Berlin wool shop’ on Skinner Street. During the spring of 1870, Mrs Thirkell in the Whitby Gazette also advertised her ‘Berlin and fancy Repository, 25a Skinner Street... The above premises are now open with a splendid assortment of Scotch Fingering, Fleecy, Berlin & all kinds of Fancy Wools’. Miss Mary Rodgers was another lady who advertised her business in the local paper in the spring of 1875 as selling, among many other fancy goods: ‘Berlin Wools. A great variety of Fancy Needlework’. Berlin-wool embroidery reached its greatest popularity in Whitby from about 1850 to the mid-1870s. After this, it seems that embroidery materials and tools were primarily sold at general drapers’ and hosiers’ shops. One such advertiser during 1875-1880 was J. Trowsdale in Bridge Street (the street visible at a later date on the image below), who stocked yarn mainly for knitting and ready-knitted garments, but also ‘Berlin & Lamb Wools’.

The opening of the Swing Bridge in 1909 also depicts Bridge Street, where many textile businesses were situated over this period. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, B 706).

The opening of the Swing Bridge in 1909 also depicts Bridge Street, where many textile businesses were situated over this period. (Courtesy: Whitby Museum, Photographic Collection, B 706).If one did not wish to do needlework oneself, ready-embroidered products could be bought from the likes of James N. Clarkson & Son. In April 1889, this firm advertised ‘White Embroidered Quilts, with table covers and Mats to match, very handsome, and quite new, Hand Embroidered Linen Sheets. Hand Initial Pillow Cases in Cotton and Linen. These should be seen.’ Even as late as May 1911, Lambert & Warters advertised ‘Hand Embroidered Linen Goods’. In other words, it was beginning to seem important to draw special attention when interior furnishings were sold containing hand-made embroidery, a sort of renaissance for a certain uneven hand-made charm that could not be obtained with machinery.

The Whitby Museum collection also contains hand-made pins, thread waxers, a buttonhole cutter, a hook for buttonhole making, buttons, button hooks and several tape measures. These mostly Victorian tape measures are often in beautifully carved wood with ivory (the tusks of narwhal, walrus or elephant) details, and some cases have even been painted with pictures. These pictures are sometimes romantic, like ‘a girl with a lamb in a landscape’ or ‘flowers and birds’, but more often, the tape measure has been worked in a combination of wood and ivory, as illustrated here. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History Collection, SOH 126). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

The Whitby Museum collection also contains hand-made pins, thread waxers, a buttonhole cutter, a hook for buttonhole making, buttons, button hooks and several tape measures. These mostly Victorian tape measures are often in beautifully carved wood with ivory (the tusks of narwhal, walrus or elephant) details, and some cases have even been painted with pictures. These pictures are sometimes romantic, like ‘a girl with a lamb in a landscape’ or ‘flowers and birds’, but more often, the tape measure has been worked in a combination of wood and ivory, as illustrated here. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History Collection, SOH 126). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation. Practically shaped wooden needle case, with room for a thimble and needles for embroidery. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History Collection, SOH103). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Practically shaped wooden needle case, with room for a thimble and needles for embroidery. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History Collection, SOH103). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.Many objects relating to the production of needlework and sewing in Whitby and its close surroundings have been studied. Tools and accessories needed for sewing could be manufactured locally, like some beautiful, unique needle cases in hand-carved wood. Though, many products used in the Whitby district by embroidering ladies were presumably made elsewhere. One example is sewing needles, produced as a cottage industry at Redditch in Worcestershire as early as the 17th century. Still, by about 1850, Redditch needle manufacture had become factory-based and a virtual monopoly. In any case, women occupied with handicrafts or various sewing looked after their needles with great care, keeping them in protective cases, which accounts for the large number of needle cases in the museum’s collection. These have mostly been made of wood, metal, or ivory, but in extreme cases, also of bronze, silver or gold. Carved, whittled or decorated, they also vary in shape from simple cylindrical sleeves to more elaborate, heavily ornamented and beautifully decorated covers. The collection also contains a beautifully carved Stanhope Needle Case with a peephole at one end and another needle case complete with thimbles.

Needles for sewing – and pins too – could also be kept in pincushions, which have been preserved in various materials and forms. The most important thing for any pincushion was to have a soft padded top section into which the needles could be pushed to hold them conveniently in place. Surviving examples include a ‘Square pin cushion’, a ‘Pin cushion made from a cowrie shell’, a ‘Pin cushion of decorated bone’, a ‘Sampler pin cushion’ and a ‘Decorated bone pin cushion’. One considerably larger pin cushion also exists, sewn from brown silk with a centre decorated with innumerable beads in the form of leaves with a decorative protective fringe. A ‘Sewing bird’ with a pincushion could also be very useful since the bird’s beak could be used as a “third hand” to grip the cloth or yarn while it was being worked. Thimbles were needed too to protect the finger – usually the middle finger – that pushed the needle through the fabric. The collection contains a considerable number of thimbles of variable appearance and material. Most are of brass, nickel or silver, but more expensive ones of ivory or gold also exist, in some cases kept in a special box.

Buttonhole cutter, 19th century. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History Collection, SOH 45). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Buttonhole cutter, 19th century. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History Collection, SOH 45). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.For the extremely popular whitework embroidery, awls were also needed for making well-formed holes wherever the embroiderer required them. These awls have survived in the shape of either a bodkin or an embroidery stiletto, ivory in both cases. The bodkin is beautifully turned, while the stiletto is shaped like a hand at the top, both ending in a sharp awl point. An interesting ‘Princess Charlotte Memorial Bodkin 1817’ has also been preserved. The Princess, the only child of the future King George IV, died that year in childbirth, and this bodkin is an example of the by no means uncommon custom of producing commemorative objects relating to the royal family.

The collection also holds a number of samples of preserved embroidery yarns in exclusive material such as ‘Ball of Embroidery Silk, ‘Skeins of Silk Thread’ and ‘Card with Gold Thread’. Other methods for the embroiderer also to wind a suitable length of thread into a large ball before beginning her work, and for this purpose, yarn-winders were used, a fair number of which have survived. These are usually made of wood in various sizes and forms, with the very finest specimen in ivory and named ‘pearl silk winder’. Also common were star-shaped ‘pearl winders’ in ivory, wood or cardboard round, which thinner embroidery yarns could be wound. One of these wooden silk winders gives a clue to the origin of the yarn: ‘Patent Mandarin Silk I & N Philips & Co Licensed By Her Majesty’s Royal Letters Patent Granted March 25th 1855.’ Thread waxers were another useful aid for the embroiderer, especially before the age of mechanical spinning, since the hand-spun thread is always somewhat uneven, and a wax cake would help strengthen or smooth out the thread, facilitating the embroiderer’s task. Finally, the Whitby collection contains three ladies’ work boxes, with room for the embroiderer’s tools, small balls of yarn and a half-finished piece of embroidery in progress. One of these boxes, from the later 19th century, is lined with velvet and still holds its full contents intact, complete with a silk pin cushion, several smaller pin cushions, wood and cardboard pearl winder stars, wooden cotton reels and thread wound onto a cardboard holder, a packet of needles marked ‘Abel Morrall’s’ and needles described as ‘Double pointed Easy sewing needle, Hayes and Crossley Sole manufacturers Alcester & London’.

Finally, a silk winder of ivory could help the embroiderer to wind thin silk thread bought in a skein onto a more convenient reel/spool to avoid the expensive thread getting tangled. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History Collection, SOH58). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Finally, a silk winder of ivory could help the embroiderer to wind thin silk thread bought in a skein onto a more convenient reel/spool to avoid the expensive thread getting tangled. (Collection: Whitby Museum, Social History Collection, SOH58). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015. (pp. 184-185 & 315-318).

- Polkinghorne, R.K. & M.I.R., The Art of Needlecraft, London 1935.

- Slater’s Directory, Directory Yorkshire – Whitby, 1864.

- Whitby Museum, Whitby Lit. & Phil., England. | Library and Archive: original papers of Whitby Gazette 1855-1911. |Photographic Collection | Social History Collection, Whitby Lit. & Phil., England: study of the entire collection linked to needlework and sewing. (Research visits 2007-2011).

- Whitby, North Yorkshire County Library. Census 1841-1901 microfilm. (Research visits in 2006).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE