ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

SERICULTURE AND CITRUS FRUITS

– 18th Century Naturalists in the Mediterranean Region and Swedish Gardens

What is apparent from the journals and letters, which are still extant, is that the so-called Linnaeus Apostles were highly motivated to follow their Instructions. This included collecting and observing anything of a useful nature that came their way during the journeys, sending plants and seeds to Carl Linnaeus or other interested parties, writing letters about their findings, keeping a clear account of their travels, developing newly written floras for the respective countries, and to be generally observant and inquisitive. If they succeeded in all that, fame, a good position and stimulating work might await them on their return home. This essay will focus on the admiration as well as the desire to increase knowledge from a Nordic perspective about some Mediterranean garden plants. Mulberry, lemons, oranges, figs, olives, almonds, plants for natural dyeing and much more were looked at in great detail – and if possible, seeds to be collected, plants kept in herbaria etc. – by two of these naturalists during the period 1749 to 1761.

![A prospect of Marseille, when the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia visited the area from 13 May to 3 June in 1761, with the naturalist Peter Forsskål (1732-1763) as one of its six members. His travel journal reveals that: ’He [Professor Sauvage] showed me the Botanical Gardens, the only aspect of foreign pleasure or splendour that had the power to captivate me.’ However, this image from the participant and cartographer Carsten Niebuhr’s (1733-1815) journal, not only visualised the sheltered harbour with ships anchored in the road, but also other aspects of their experiences in the area. The focal point of the three depicted naturalists – most probably members of their expedition – were dressed entirely according to European fashion of the time: a coat with flared tails down to the knees, a somewhat shorter waistcoat underneath (not visible), white cuffs and collar, a hat, breeches and hose. Drawing, collecting and observing were essential parts of their instructions – in this case, plants were not in focus, but instead, the sand- and limestone mountainous rocks. (In the book: Niebuhr…1774. Vol. One. Tab. XII).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/1-a-niebuhr-900x435.jpg) A prospect of Marseille, when the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia visited the area from 13 May to 3 June in 1761, with the naturalist Peter Forsskål (1732-1763) as one of its six members. His travel journal reveals that: ’He [Professor Sauvage] showed me the Botanical Gardens, the only aspect of foreign pleasure or splendour that had the power to captivate me.’ However, this image from the participant and cartographer Carsten Niebuhr’s (1733-1815) journal, not only visualised the sheltered harbour with ships anchored in the road, but also other aspects of their experiences in the area. The focal point of the three depicted naturalists – most probably members of their expedition – were dressed entirely according to European fashion of the time: a coat with flared tails down to the knees, a somewhat shorter waistcoat underneath (not visible), white cuffs and collar, a hat, breeches and hose. Drawing, collecting and observing were essential parts of their instructions – in this case, plants were not in focus, but instead, the sand- and limestone mountainous rocks. (In the book: Niebuhr…1774. Vol. One. Tab. XII).

A prospect of Marseille, when the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia visited the area from 13 May to 3 June in 1761, with the naturalist Peter Forsskål (1732-1763) as one of its six members. His travel journal reveals that: ’He [Professor Sauvage] showed me the Botanical Gardens, the only aspect of foreign pleasure or splendour that had the power to captivate me.’ However, this image from the participant and cartographer Carsten Niebuhr’s (1733-1815) journal, not only visualised the sheltered harbour with ships anchored in the road, but also other aspects of their experiences in the area. The focal point of the three depicted naturalists – most probably members of their expedition – were dressed entirely according to European fashion of the time: a coat with flared tails down to the knees, a somewhat shorter waistcoat underneath (not visible), white cuffs and collar, a hat, breeches and hose. Drawing, collecting and observing were essential parts of their instructions – in this case, plants were not in focus, but instead, the sand- and limestone mountainous rocks. (In the book: Niebuhr…1774. Vol. One. Tab. XII). This contemporary map of the Mediterranean gives a good overview of the areas visited by the two naturalists – in the harbours and neighbouring surroundings of Marseille, Valletta, Constantinople, Smyrna, Sidon, Alexandria and Cairo. | Map by the cartographer Tobias Conrad Lotter, Augsburg, in 1770. (Courtesy: Lund University Library, De la Gardieska kartsamlingen, Lund, Sweden. Alvin-record: 205080. Public Domain).

This contemporary map of the Mediterranean gives a good overview of the areas visited by the two naturalists – in the harbours and neighbouring surroundings of Marseille, Valletta, Constantinople, Smyrna, Sidon, Alexandria and Cairo. | Map by the cartographer Tobias Conrad Lotter, Augsburg, in 1770. (Courtesy: Lund University Library, De la Gardieska kartsamlingen, Lund, Sweden. Alvin-record: 205080. Public Domain).Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752) was the first of these two former Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) students who embarked on a lengthy natural history journey to the Mediterranean region. His travels started from Stockholm in August 1749, and the sea voyage ran its course without any significant problems; he often seems to have enjoyed the beautiful weather. It was only in Sardinia that the ship hit a troublesome storm. The group arrived at Smyrna on 27 November where, on repeated field excursions, Hasselquist explored the area. He lodged with the Swedish consul Anders Rydelius where he had a good life, often in the company of consuls from other countries. Orange trees, vines, dates, olives, palm trees, ivy, figs and pomegranate were repeatedly admired in gardens and vineyards. From February to March 1750, he also made comparisons with possibilities and obstacles to grow some of these plants in his home country, including:

- ‘Art has been but of small assistance to the gardens here, except in planting a few Orange-trees, which do not grow wild. Nature in this place is amiable; but, if a little art was used, the gardens here would soon possess much greater beauty, than those in our Northern Europe, which require so much cost and labour; Orange-trees grow here in abundance, nor does anybody care to pluck the fruit, which remains on the trees the whole year, until the flowering season, when it falls off.’

- ‘On the other side were Fig-trees, Almond-trees, Orange-trees, Oriental Plane-tree, (Platanus orientalis) &c. which with us are kept in hothouses and pots, but here in the open air left to nature; I took however notice, that the hard frost towards the latter end of February had ravaged the Orange-trees, whose leaves and fruit were entirely destroyed.’

In May 1750, the voyage proceeded to Alexandria. During his Egyptian sojourn, he continued intensively collecting natural history specimens, concentrating primarily on botanical ones. The traveller often wrote letters to Linnaeus, sometimes enclosing samples of plants and seeds. On the 15th of this month, he rode out to see the gardens of Alexandria and noted in his journal: ‘In the place I had hitherto resided, I had walked in gardens of Lemon, Orange, Fig and Mulberry trees. I had seen whole fields filled with the finest vines. I had travelled through forests of Olive-trees and rested myself in the agreeable groves of Cypresses, but I saw not one of these Eastern glories in Egypt…’

A year later, in April 1751, the group arrived in Palestine, where he not only continued his explorations of natural history but also visited Jerusalem, Jericho, the Dead Sea, Bethlehem, Nazareth, Tabor and Sidon – along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean – arriving there in May 1751. Fredrik Hasselquist was amazed by the riches of the garden's abundance of mulberry trees etc.:

- ’The gardens in this town are the most remarkable things in it, and in these consist its riches; wherefore my first business was to see them. They extend an entire French mile around the town, and contain Pomegranate-trees, Apricots, Figs, Almonds, Oranges, Lemons and Plums, in such quantities, that the town can yearly furnish other places with considerable cargoes of these fruits, but the most numerous, and in which their riches chiefly consist, are Mulberry-trees, on which they feed an infinite number of silk worms.’

From there are also mentioned the circumstances of the widespread superstition that existed concerning the processes of sericulture. The popular belief, especially among women, whom he regarded as extra susceptible to superstition, was that any form of work to do with sericulture would be lost if a stranger was allowed to see the worms. That was the reason why it was only after eighteen months in the Mediterranean region that he managed to get a chance to study how silk was made. His report indicates that in many gardens, there was a hut made of twigs where the worms were fed, grew and spun their cocoons. Due to his assistant having the right contacts, he was allowed to visit such a hut in order to study the process; shortly after that Hasselquist made a meticulous description of the sericulture in Syria, where he learnt that in popular belief, ants and thunder were their worst enemies. To achieve the best results the worms were treated as follows:

- ‘The eggs are laid in a warm room: the women often carry them in their bosoms, or lay them between the bolsters in a bed, where they are hatched; and to the Worms they immediately give Mulberry leaves, to which they stick fast. They eat and grow for forty days, all that time laying on stages made of reed, in an arbour formed of boughs of trees. The worms are covered once a day with Mulberry leaves; and creeping upon these leaves, they seem almost to cover them, by the time a new layer of leaves is to be put over them. When they begin to change colour, the people set up branches of various trees; these they climb up, and begin to spin. When they have left off spinning, they are taken from their habitations; such as are to be used for silk, which is by much the greatest part, are laid in hot water, and wound on a reel; the remainder is kept alive to be transformed into moths, for preserving the breed. When the Moths come forth, the attendants spread a black carpet in the room; on this, they lay their eggs, which are preserved in small bags.’

The overall aim in Sweden for the future of sericulture was to make it possible for them to produce desirable silk fabrics by textile manufacturers, which came to have limited success. Carl Linnaeus, as a member of the innermost circle of those advocating sericulture in Sweden, together with Mårten Triewald (1691-1747) and Eric Gustaf Lidbeck (1724-1803), was fundamental to the former pupils’ attention paid to the subject when travelling abroad. Linnaeus himself carried out studies into the changes to succeed with sericulture during his provincial Swedish journeys in 1746 and 1749, which, combined with the encouragement to publish pamphlets, to inspire trial plantings and legislative regulations, would contribute to improving possibilities for the cultivation of silkworms (even if the winter climate was unsuitably cold).

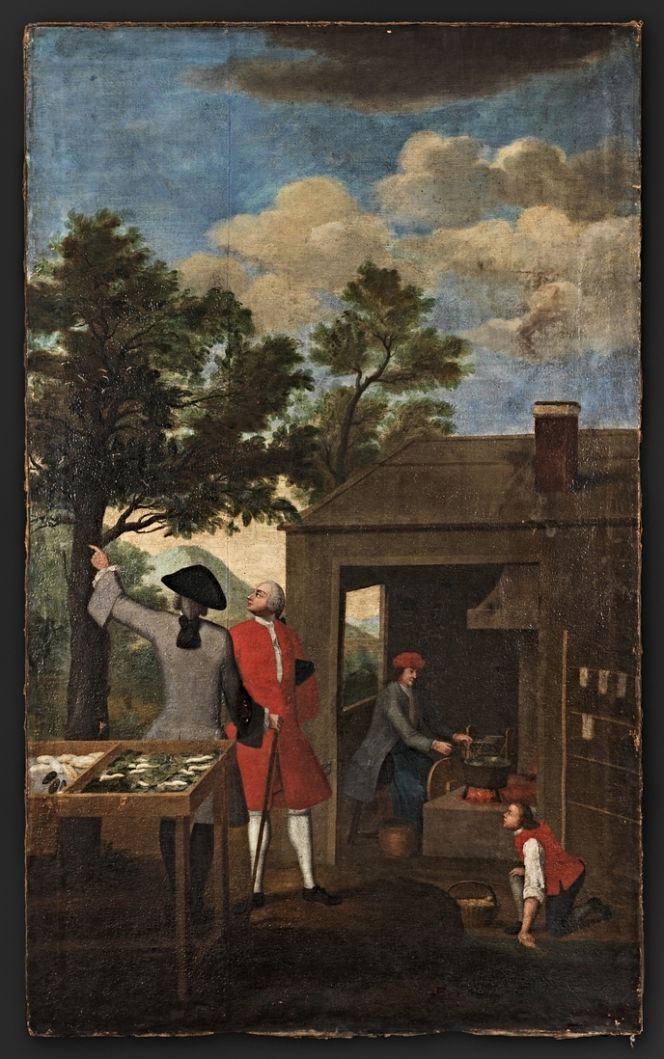

This depiction of sericulture at – Åstorp house, Hållsta, Södermanland province – in 1750s Sweden is an interesting comparison to these sericulture ideas. A small manor house like this, together with larger estates of the nobility and royalty alike, were the forerunners of exotic gardening from all sorts of perspectives. Growing mulberry trees to feed the silkworm was one such category. Whilst other areas of activity were to construct orangeries where citrus fruits like oranges and lemons, together with a selection of other non-frost resistant plants, all could be kept during the winter months in large pots, if necessary in hothouses. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0145810. Oil on canvas by an unknown artist. DigitaltMuseum).

This depiction of sericulture at – Åstorp house, Hållsta, Södermanland province – in 1750s Sweden is an interesting comparison to these sericulture ideas. A small manor house like this, together with larger estates of the nobility and royalty alike, were the forerunners of exotic gardening from all sorts of perspectives. Growing mulberry trees to feed the silkworm was one such category. Whilst other areas of activity were to construct orangeries where citrus fruits like oranges and lemons, together with a selection of other non-frost resistant plants, all could be kept during the winter months in large pots, if necessary in hothouses. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0145810. Oil on canvas by an unknown artist. DigitaltMuseum). One such example from a Swedish perspective is clearly visualised on the top oil on canvas,’Orange tree in an urn’, by the painter David von Cöln in 1733. This is demonstrated in the form of a luxurious exotic fruit-bearing plant, where each fruit had its own decorative, protective wooden stand, oranges which had the potential to be served to specially selected and distinguished guests of the wealthy household…

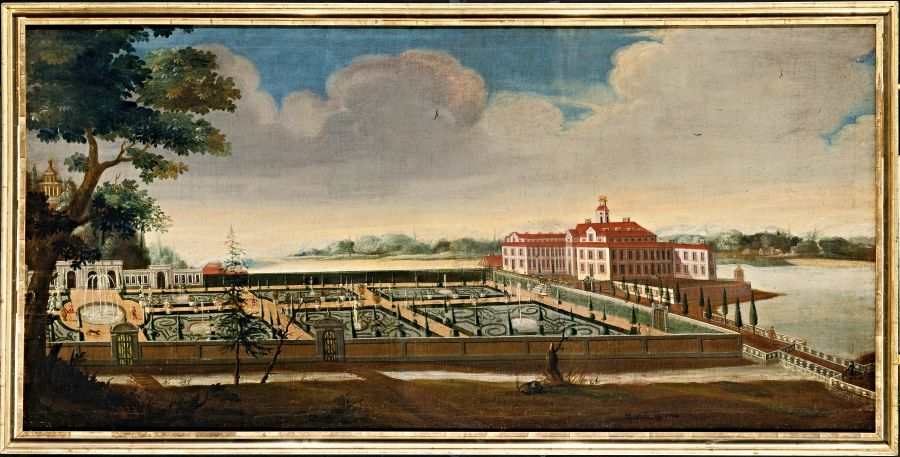

One such example from a Swedish perspective is clearly visualised on the top oil on canvas,’Orange tree in an urn’, by the painter David von Cöln in 1733. This is demonstrated in the form of a luxurious exotic fruit-bearing plant, where each fruit had its own decorative, protective wooden stand, oranges which had the potential to be served to specially selected and distinguished guests of the wealthy household…  With a second painting, ‘View of Ulriksdal from the South’ – closely situated in Stockholm – by the very same artist, David von Cöln, in 1732. In this view of a summer's day, a rich selection of features is on display, including a number of urns placed on pedestals in the strictly ornamental Royal garden. To the left in the picture, the orangery is clearly visible, where plants like citrus fruits and mulberry trees were kept during the long cold winters. An interesting connection between Ulriksdal Palace and the two young travelling naturalists’ observations was their former teacher Carl Linnaeus. Due to that, he assisted Queen Lovisa Ulrika (1720-1782) with her extensive natural history collections on multiple occasions, particularly during the 1750s. (Courtesy: National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. No: NM 4760 & No: NMGrh 503. Public Domain).

With a second painting, ‘View of Ulriksdal from the South’ – closely situated in Stockholm – by the very same artist, David von Cöln, in 1732. In this view of a summer's day, a rich selection of features is on display, including a number of urns placed on pedestals in the strictly ornamental Royal garden. To the left in the picture, the orangery is clearly visible, where plants like citrus fruits and mulberry trees were kept during the long cold winters. An interesting connection between Ulriksdal Palace and the two young travelling naturalists’ observations was their former teacher Carl Linnaeus. Due to that, he assisted Queen Lovisa Ulrika (1720-1782) with her extensive natural history collections on multiple occasions, particularly during the 1750s. (Courtesy: National Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. No: NM 4760 & No: NMGrh 503. Public Domain).A decade after Fredrik Hasselquist’s journey, the naturalist Peter Forskål (1732-1763) embarked on his travels. In the autumn of 1760, he and five other participants were assembled in København (Copenhagen) to determine their plans for Den Arabiske Rejse (The Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia), which they began on 7 January 1761. The group managed to get away first on the fourth attempt at leaving Helsingør on 12 March, arriving in the Mediterranean in the month of May. Visits were paid to Malta, from where he gave accounts of lemon and Seville oranges together with some further thoughts on garden designs. The company stayed on the island from 14 to 20 June in 1761, when he included the following mixed experience of a prominent garden:

- ‘St Antoine on the road to Citta Vecchio is a garden that belongs to the Grand Master. It has been constructed in a particular style, new and to me extremely disagreeable. The ground has been divided into a large number of small squares separated by flat paths made of masonry, five alnar wide. Each is flat, but terraced to fit its location, with some parts higher than others, all of limestone. On either side of the paths are square pillars five alnar apart. Each pillar supports a grapevine that branches over the walk to form a flat roof. Where the paths meet are roundels with fountains. The squares formed by the alleys contain nothing but orange and lemon trees. The kitchen garden is situated lower down, but without any similar division into sections. All this obviously cost a lot of money, but it seemed to me that a walkway of hard stone was quite unsuitable for a garden promenade…’

The journey continued towards Constantinople, the surrounding areas and the island of Rhodes, where Forsskål did numerous fieldworks for almost three months – from 30 July to 26 September in 1761. Outside Constantinople, for instance, he noted that: ‘Having had a quick look at the countryside outside the city, and the condition of the gardens within it, I wanted to find out what I could extract from the sea near here that would be new to natural history.’ Like several of the other travelling apostles, he was a keen spokesman for the advantages of sericulture in all places where mulberry trees could possibly thrive, and that was the case in and around Constantinople, where he noted with disappointment: ‘Morus alba et nigra is found only too plentifully in this region, though the cultivation of silk is not practised. The Europeans who live here offer the feeble excuse so often heard in Sweden and elsewhere that the climate is unsuitable for this activity.’ Instead, the inhabitants were said to be only interested in taking care of the fruit from the mulberry trees. He mentioned mulberry trees as well as citrus fruit in gardens when the travel company had reached Rhodes as well: ’Symbolimarasch is a village near the town, inhabited by Greeks, whose bishop lives there. Next to his house is a garden, which I immediately went to see. The trees here were fig, lemon, mulberry and pomegranate.’ About a week later, their ship reached the coast of Egypt, a country which was one of the main destinations where the expedition carried out various work lasting a year. From Alexandria, he noted that the proximity of water was the reason why most of the plantations and date palm gardens were located here.

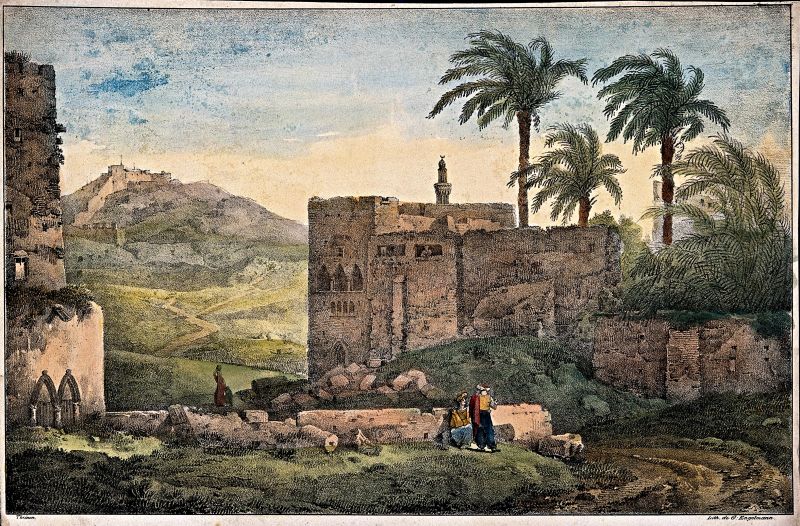

Even if this lithograph ‘Hopital des Grecs à Alexandrie’ dates from the early 19th century, the impression of gardens were noticeably similar to Peter Forsskål’s journal observations from Alexandria in 1761. He wrote: ‘Botany can keep a nature enthusiast fully occupied in this country, even though there are fewer plants here than in Europe. On my first day in Alexandria, I went to look at the nearest gardens… Garden walls here are high, but palm trees tower above them like a most beautiful forest.’ (Courtesy: Wellcome Library no. 15385i, by Gottfried Engelmann (1788-1839) after Thienen).

Even if this lithograph ‘Hopital des Grecs à Alexandrie’ dates from the early 19th century, the impression of gardens were noticeably similar to Peter Forsskål’s journal observations from Alexandria in 1761. He wrote: ‘Botany can keep a nature enthusiast fully occupied in this country, even though there are fewer plants here than in Europe. On my first day in Alexandria, I went to look at the nearest gardens… Garden walls here are high, but palm trees tower above them like a most beautiful forest.’ (Courtesy: Wellcome Library no. 15385i, by Gottfried Engelmann (1788-1839) after Thienen).Overall Forsskål’s botanical work came to be extensible from Egypt. Still, the quoted section below interestingly also reveals his aims to observe and increase knowledge of the local flora of Alexandria to be able to expand into future ideas, possibilities and obstacles of “plant hunting”, which could benefit European gardens.

- ‘Fertiliser is never used in the gardens, since they assured me that this would damage the soil, but manure is used as fuel, and is expensive. The soil seems sandy and meagre, but is nonetheless remarkably fertile. It is not the actual Nile water itself that brings fertility, so much as the sediment that comes with it when it floods. Thus everything stems from constant watering. This is exactly why some European gardens are so fertile;…When I saw such well-cultivated land, and found all around me such a new and magnificent flora that I had hardly seen any sign of in the forced climate of hothouses growing so freely, I only wished that some lover of the sciences like the English consul in Smyrna, Gerard, who I think wanted to finance a botanical garden here, could receive plants from India via Mocha and Cairo. Also, African plants could be fetched from neighbouring lands, and Egyptian wild plants could be brought in alive by Arabs engaged for the purpose. How easy it would be then for Alexandria to become a horticultural school for all the botanical gardens of Europe! But to build up my own botanical collection I was going to need more than planning and wishing. I had to go further afield to search for the plants of Egypt since the plantations in the city had nothing to offer me that I had not already seen…’

In concluding words about the two naturalists who sadly died young during their travels – Fredrik Hasselquist at 30 in Smyrna, 1752 and Peter Forsskål, 31 years old in Jemen. As the natural historian of the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia, Forsskål received a yearly salary of 500 Rdl. [rix dollar] during the two years before the journey. Together with the privilege to collect a Danish pension after his return home, which never became realised due to his premature death. His collections and written observations were brought back by the sole survivor – Carsten Niebuhr – of the expedition to Denmark in 1767. Whilst Hasselquist’s financial situation was complex. Initially, his journey had been financed by several academic scholarships together with collected funds from various institutions and private persons. However, there were still not enough funds to cover the costs during the journey, so he was obliged to put himself into debt to be able to carry on his mission. After Hasselquist died in 1752, Carl Linnaeus was extremely anxious to get the whole affair sorted out and arrange for the young apostle’s collected natural specimens and objects of curiosity to be transported to Sweden. Queen Lovisa Ulrika of Sweden (she also had one of her residences at Ulriksdal Palace as discussed and illustrated above), who had already embarked on a collection of natural history specimens in the 1740s, was in the end, persuaded to help. She had the financial resources to buy Hasselquist’s collection while also wishing to augment her already considerable natural history cabinet. She redeemed the collection in 1754 at a price of 14,000 Daler in copper coins [Rixdollar copper coin], comprising a considerable quantity of natural history objects, manuscripts, antiques and ethnographic objects from the areas he visited during his travels.

Sources:

- Forsskål, Peter (ed. Uggla, Arvid Hj.), Petrus Forsskåls Dagbok 1761-1763. Resa till Lycklige Arabien, Uppsala 1950.

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Vol. Four: Journals of Fredrik Hasselquist & Peter Forsskål. | Vol. Eight: pp. 31-37).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (Read more about these two naturalists’ textile observations. pp. 132-139 & 163-196).

- Hasselquist, Fredrik, Iter Palaestinum eller Resa til Heliga Landet förrättad ifrån år 1749 til 1752, utgifven af Carl Linnaeus, Stockholm 1757.

- Laine, Merit, En Minerva för vår Nord – Lovisa Ulrika som samlar, uppdragsgivare och byggherre, Uppsala 1998.

- Niebuhr, Carsten. Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegender Ländern. Vol. One, Copenhagen, 1774.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE