ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

SMELLS, FRAGRANCES AND ODOURS

– Observations of Textile Materials and Dyes by 18th Century Naturalists

Carl Linnaeus and some of his seventeen apostles who travelled to more than 50 countries, made frequent reflections on smell, scent, fragrance, odour or stench in their journals. These notes were at times linked to textiles – in the context of sleeping habits, raw materials or natural dyes. This essay will look closely into such sensory experiences from Sweden, Suriname, Java, on-board an East India ship and in the North American colonies. However, for obvious reasons, different smells were more often related to food, water, examined plants or other daily life necessities as they came across during their natural history expeditions. All these descriptions could be surprisingly detailed, which may point at how important 18th century humankind regarded the sense of smell – which could be noted as attractive, pleasant, good, agreeable, powerful, strong, bad, disgusting, repulsive, nauseous, refreshing, musky, pungent or aromatic.

The Royal Academy Botanical Garden (also called Linnaeus’ Garden) in Uppsala, here depicted in 1770. This garden must frequently have been visited by all of Carl Linnaeus’ disciples during their student years. At this time, he had been the director for almost 30 years and arranged it in a particular order according to his Sexual System of plants. Pleasant or unpleasant smell were doubtless one of the sensory experiences in this well-kept botanical garden. To notice everything from fragrances to stench became a mode of observation in writings, which the seventeen long-distance travelling apostles continued to reflect on when describing plant specimens in their journals. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library: alvin-record:97288, part of image. After an engraving from 1769. Public Domain).

The Royal Academy Botanical Garden (also called Linnaeus’ Garden) in Uppsala, here depicted in 1770. This garden must frequently have been visited by all of Carl Linnaeus’ disciples during their student years. At this time, he had been the director for almost 30 years and arranged it in a particular order according to his Sexual System of plants. Pleasant or unpleasant smell were doubtless one of the sensory experiences in this well-kept botanical garden. To notice everything from fragrances to stench became a mode of observation in writings, which the seventeen long-distance travelling apostles continued to reflect on when describing plant specimens in their journals. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library: alvin-record:97288, part of image. After an engraving from 1769. Public Domain). In the same decade as Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) became director of the botanical garden and Professor of Medicine at Uppsala University (1741), he also made three provincial tours in Sweden. Hemp as a textile fibre was noted for instance, and the unpleasant smell also had to be taken into account for this plant. From the Öland and Gotland Journey, he noted on 9 August 1741 in his journal: ‘...the hemp fields stood beautiful’ and on this island the plant encountered the same poor preconditions for survival as flax, too windy and dry, while at the same time the peasants bemoaned the lack of ‘plots where they could ret such goods’ (11 June 1741). Whilst exactly eight years later on the Skåne Journey, at Åkarp village, between Malmö and Lund, the soil was all the better for hemp, and on 11 June 1749 Linnaeus wrote from there: ‘Hemp is sown here a lot on the farms, but she should not be grown close to the houses as she emits a strong and harmful smell’.

Another subject which caught his interest during the same journey was fine sheepskin gloves. In the coastal city of Malmö where novel ideas reached the population earlier than in the provinces, there was a complete lack of skin-processing craftsmen as a group at the time of Linnaeus’ visit there, whilst the town in 1717 numbered four individuals in this trade. Well-thought-of sheepskin gloves were nevertheless still made there and described as follows on 16 June 1749:

- ‘Shorn sheepskins, mostly for gloves, were made of the very best kind in Malmö among all the places in Sweden, so that Malmö sheepskin gloves were in demand from all over the country for their suppleness and special smell. The sheepskins which are used for that are to be found in Skåne, Bornholm and Denmark, of which the skins from Bornholm were regarded as the best. Yet, it is not the fattest sheep that yield the best skins. The skins are prepared using sallow bark and not willow bark, which is boiled with bärman or yeast and clean water until the material is well boiled.’

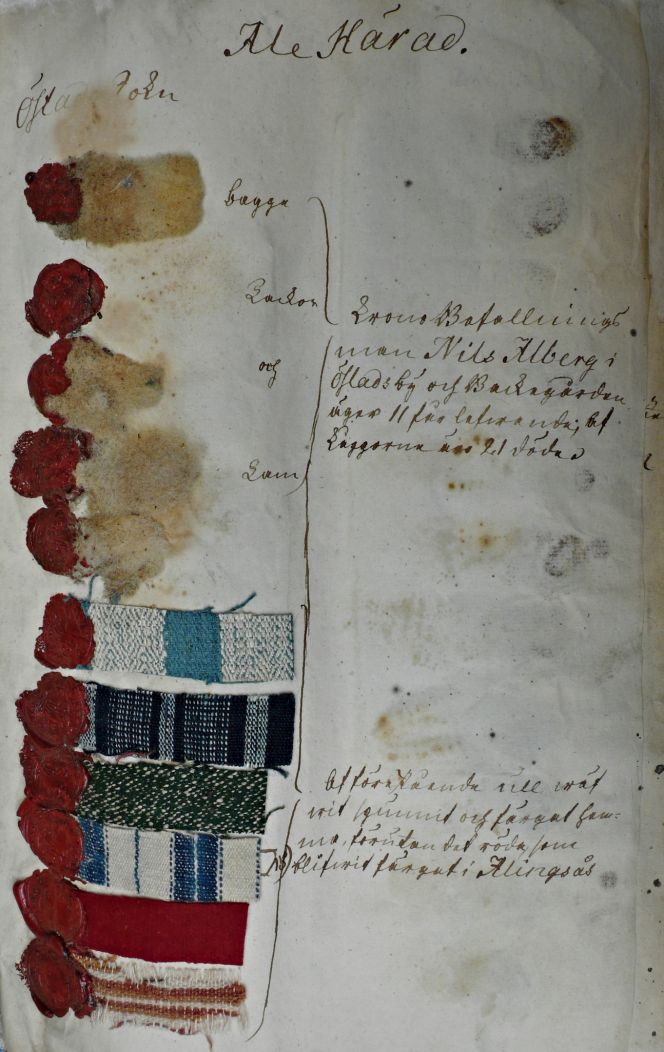

Before the wool could be spun it had to be sorted and carded, which did capture Linnaeus’ attention on the Västergötland Journey, 7 July 1746. He wrote in his journal: ‘Manufactures at Alingsås with all the workshops established here and visited on this day. The sorting of the wool, wool in all its many varieties being separated by fingers. Here we saw the wool being pounded free of its impurities on a table plaited from coils.’ In that context, he also mentioned that the workers here worked in particularly unhealthy conditions, but glossed over it as he wanted to make the manufactures appear in an entirely positive light. ‘The wool combing… the ovens emitted a steady smell, especially in winter, so long as the windows were not allowed to be opened; nevertheless we did not notice that the workers suffered any other disadvantage than the one and only one that they had lost their sense of smell and that the smallest amount of strong beverages made them drink-taken.’ An interesting comparison is these illustrated wool and fabric samples from the jurisdictional district of Ale in 1754, in the province of Västergötland which Linnaeus had visited a decade earlier. Evidently there was a direct connection to the manufacture town Alingsås as well as to local woollen handicraft, due to that one of the notes reads: ‘That above wool has been woven, spun and dyed at home, besides the red which was dyed in Alingsås’. (Collection: The National Archive (Riksarkivet), Stockholm…1754). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.

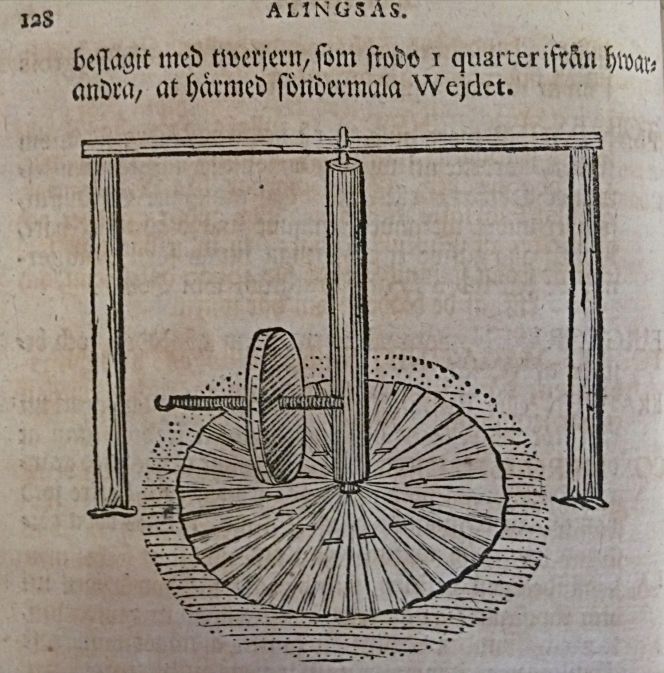

Before the wool could be spun it had to be sorted and carded, which did capture Linnaeus’ attention on the Västergötland Journey, 7 July 1746. He wrote in his journal: ‘Manufactures at Alingsås with all the workshops established here and visited on this day. The sorting of the wool, wool in all its many varieties being separated by fingers. Here we saw the wool being pounded free of its impurities on a table plaited from coils.’ In that context, he also mentioned that the workers here worked in particularly unhealthy conditions, but glossed over it as he wanted to make the manufactures appear in an entirely positive light. ‘The wool combing… the ovens emitted a steady smell, especially in winter, so long as the windows were not allowed to be opened; nevertheless we did not notice that the workers suffered any other disadvantage than the one and only one that they had lost their sense of smell and that the smallest amount of strong beverages made them drink-taken.’ An interesting comparison is these illustrated wool and fabric samples from the jurisdictional district of Ale in 1754, in the province of Västergötland which Linnaeus had visited a decade earlier. Evidently there was a direct connection to the manufacture town Alingsås as well as to local woollen handicraft, due to that one of the notes reads: ‘That above wool has been woven, spun and dyed at home, besides the red which was dyed in Alingsås’. (Collection: The National Archive (Riksarkivet), Stockholm…1754). Photo: Viveka Hansen, The IK Foundation.  The woad mill described and illustrated in Linnaeus’ Västergötland Journey from 1746. A textile dyeing tradition, which may be compared with observations with one of his apostles, Pehr Kalm (1716-1779), who also made a provincial tour in Sweden during the 1740s. Among many matters, Kalm’s detailed journal from the province of Bohuslän registered the tradition of dyeing blue with woad. (From: Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa…, 1747, p. 128).

The woad mill described and illustrated in Linnaeus’ Västergötland Journey from 1746. A textile dyeing tradition, which may be compared with observations with one of his apostles, Pehr Kalm (1716-1779), who also made a provincial tour in Sweden during the 1740s. Among many matters, Kalm’s detailed journal from the province of Bohuslän registered the tradition of dyeing blue with woad. (From: Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa…, 1747, p. 128). Dyeing blue was a complex process, and above all, getting the dye-vat to its correct state of fermentation was something that required experience on the part of the dyer. For that reason, it was common, among the peasant women in particular who dyed with woad, to use urine for the fermentation which simplified the procedure. That method was also recommended in contemporary dye books, but the drawback was, of course, the smell. Urine also came in handy when dyeing red with lichen, of which Pehr Kalm gave a thorough description from Bohuslän on 17 August 1742:

- ‘Then one puts it in an earthenware pot with urine and leaves it to stand for a whole month. When one wishes to use it, one takes a spoonful or more, depending on how much one has to dye, from the pot and puts it in the water in the cauldron, then lets it boil a little and then puts therein the cloth which is to be dyed red.’

Some more than five years later, Kalm departed in October 1747 from Uppland, via Göteborg and Norway to England. In the coming year, he sailed to the main destination –the North American colonies – where he travelled in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Delaware and the southeastern parts of what is today Canada. His travel journal includes frequent notes about how he experienced the sense of smell. Particularly enlightening from a textile perspective is this observation of sassafras wood, beds and cloth chests on 21 November in 1748, from the community in Raccoon, New Jersey:

- ‘Some people get their bedposts made of sassafras wood, in order to expel the bugs; for its strong scent it is said prevents those vermin from settling in them. For two or three years together this has the desired effect; or about as long as the wood keeps its strong aromatic smell; but after that time it has been observed to lose it effect. A joiner showed me a bed, which he had made for himself, the posts of which were of sassafras wood, but as it was ten or twelve years old, there were so many bugs in it, that it seemed likely, they would not let him sleep peaceably. Some Englishmen related, that some years ago it had been customary in London, to drink a kind of tea of the flowers of sassafras, because it was looked upon as very salutary; but upon recollecting that the same potion was much used against the venereal disease, it was soon left off, lest those that used it, should be looked upon as infected with that disease. In Pennsylvania some people put chips of sassafras into their chests, where they keep all sorts of woollen stuffs, in order to expel the moths (or Larvae, or caterpillars of moths or tinies) which commonly settle in them in summer. The root keeps its smell for a long while: I have seen one which had lain five or six years in the drawer of a table, and still preserved the strength of its scent.’

The Linnaeus’ apostle Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) instead travelled with a Swedish East India Company ship in 1750 to Canton (today Guangzhou) as a ship’s chaplain-cum-naturalist. His travel journal gives a detail reflection of how he was sleeping on the lid of the chest which he had bought for himself on the return voyage onboard the ship from China. On 2 November in 1751 he noted that: ‘Rose wood is heavy, red, has a fine smell, has black and light veins, and is very dear. A certain species of light-brown wood is much esteemed here, and the Europeans have chests made of it… The light-brown wood, of which Europeans get chests made for their clothes, is sold pretty dear. I bought a chest of five feet long, two feet broad, varnished over, and plated with brass, to lay my clothes in, for 100 dollars of copper…’ (Pehr Osbeck’s chest, in private ownership). Photo: The IK Foundation.

The Linnaeus’ apostle Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) instead travelled with a Swedish East India Company ship in 1750 to Canton (today Guangzhou) as a ship’s chaplain-cum-naturalist. His travel journal gives a detail reflection of how he was sleeping on the lid of the chest which he had bought for himself on the return voyage onboard the ship from China. On 2 November in 1751 he noted that: ‘Rose wood is heavy, red, has a fine smell, has black and light veins, and is very dear. A certain species of light-brown wood is much esteemed here, and the Europeans have chests made of it… The light-brown wood, of which Europeans get chests made for their clothes, is sold pretty dear. I bought a chest of five feet long, two feet broad, varnished over, and plated with brass, to lay my clothes in, for 100 dollars of copper…’ (Pehr Osbeck’s chest, in private ownership). Photo: The IK Foundation.

![Pehr Osbeck made one further observation about the connection between cloths and smell regarding the moth-resistant plant Bæckea frutescens. It was not only described in the journal, but also shown in an illustration, enclosed in both the Swedish edition of 1757 and an English edition, printed in 1771. From his journal on 27 September in 1751 it was recorded that: ’Bæckea frutescens [Tab. i.] is a little shrub, which grows above a quarter of a yard high, looks like Mugwort, and smells agreeably. On my return I put some of it into my box, which preserved my cloths from tinias, or moths. The Chinese call it Tiongma. This was the first time that it was carried to Europe. It is described in Linn. Species Plantarum: its flowers are small, white, and smell somewhat like primroses.’ (Botanical plate, from: Osbeck…1757).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/5a-pehr-osbeck-1757-664x1150.jpg) Pehr Osbeck made one further observation about the connection between cloths and smell regarding the moth-resistant plant Bæckea frutescens. It was not only described in the journal, but also shown in an illustration, enclosed in both the Swedish edition of 1757 and an English edition, printed in 1771. From his journal on 27 September in 1751 it was recorded that: ’Bæckea frutescens [Tab. i.] is a little shrub, which grows above a quarter of a yard high, looks like Mugwort, and smells agreeably. On my return I put some of it into my box, which preserved my cloths from tinias, or moths. The Chinese call it Tiongma. This was the first time that it was carried to Europe. It is described in Linn. Species Plantarum: its flowers are small, white, and smell somewhat like primroses.’ (Botanical plate, from: Osbeck…1757).

Pehr Osbeck made one further observation about the connection between cloths and smell regarding the moth-resistant plant Bæckea frutescens. It was not only described in the journal, but also shown in an illustration, enclosed in both the Swedish edition of 1757 and an English edition, printed in 1771. From his journal on 27 September in 1751 it was recorded that: ’Bæckea frutescens [Tab. i.] is a little shrub, which grows above a quarter of a yard high, looks like Mugwort, and smells agreeably. On my return I put some of it into my box, which preserved my cloths from tinias, or moths. The Chinese call it Tiongma. This was the first time that it was carried to Europe. It is described in Linn. Species Plantarum: its flowers are small, white, and smell somewhat like primroses.’ (Botanical plate, from: Osbeck…1757). In another part of the world in the 1750s, the arrival and early days in the Dutch colony Suriname were particularly difficult for the Linnaeus’ apostle Daniel Rolander (1723-1793): a combination of heat, humidity, strong smells, insects buzzing, “dangerous animals” and a general feeling of uneasiness. Sleeping and getting some night rest was also extremely trying, at the same time as Rolander had to get used to sleeping in a hammock woven out of cotton. Yet that berth was thought considerably more comfortable in the constant heat than a warm bed. Overall, he frequently lingered in his journal on intense, pleasant, nauseating etc odours from plants in the tropical climate, he even was the naturalist – among the long-distance travellers – who most frequently referred to his sensory experience of odours, fragrance, smell or scent for almost each and every plants he came across. For instance on 24 December 1755 in Paramaribo: Cordia suaveolens… ‘I often took its branches, gathered in a bundle, to my room; their lovely odour was wonderfully refreshing. At night when I could not sleep, I would place these branches in the hammock, and before long, a gentle sleep would steal over me.’

The problem with heat and pungent smells were also mentioned by the apostle Daniel Solander’s (1733-1782) travel companion, Joseph Banks (1743-1820) in his travel journal, at a time when the company stayed in Batavia, the capital of the Dutch East Indies, (today Jakarta), on the homeward leg of James Cook’s (1728-1779) first voyage in 1770. Jasmine and other scented flowers were in great use for putting in between the bedclothes in this place, a method for improving the indoor air in the unhealthy city, from the Europeans’ viewpoint, and at the same time nourishing a hope that the flowers might be efficacious in preventing tropical diseases. Sensations of smell – be they pleasant fragrances, odours, or whenever reason arose for the quality of a commodity to be determined – that sense was important and many a time helped to clarify the travelling naturalists’ experiences.

Sources:

- Banks, Joseph, The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks – 1768-1771. Ed. by J. C. Beaglehole, 2 vol., Sydney 1963.

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Vol. Three: Pehr Kalm & Daniel Rolander’s journals. | Vol. Seven: Pehr Osbeck’s journal).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 70, 221 & 293-300).

- Kalm, Pehr, Wästgötha och Bohusländska resa 1742, Stockholm 1977.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Carl Linnæi ... Öländska och Gothländska resa, åhr 1741..., Stockholm & Upsala 1745.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgötaresa…förrättad åhr 1746..., Stockholm 1747.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Skånska resa…förrättad år 1749..., Stockholm 1751.

- Osbeck, Pehr, Dagbok Öfwer en Ostindisk Resa, Åren 1750, 1751, 1752…, Stockholm 1757.

- Osbeck, Peter [Pehr], A Voyage to China and the East Indies, 2 vol., London 1771.

- The National Archive (Riksarkivet), Stockholm, Sweden. ‘Kommerskollegium Kammarkontoret’, Sample book with wool- and fabric samples, 1754 (research visit in 2014).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE