ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

SMUGGLING OF TEXTILES AND MAPS

– On 18th Century Natural History Journeys

Several of Carl Linnaeus’ seventeen apostles made notes in their journals on long-distance travels from 1745 to 1799 about problems or opportunities arising in harbours, when anchoring on the road or in a river leading up to their destination. Smuggling, passports, quarantine, a myriad of obstacles to trade, customs officers with loaded rifles, and inspections of all luggage and sealed goods were some of the issues. At times, various textile wares like fine silks or cottons, desirable clothing or maps were particularly in focus. Journal notes of such observations by the travelling naturalists will be looked at more closely in this essay. Together with a few contemporary illustrations from geographical areas visited by these men and a Swedish East India sales catalogue, further aspects of this context are revealed.

![When arriving in Batavia [today Jakarta] in May 1775, the naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) onboard a Dutch East Company ship, made extensive observations of all sorts of everyday matters in his travel journal. For instance, his clothes and other luggage were briefly mentioned in connection to the customhouses and tolls: ‘Institutions which, in countries where commerce is expected to flourish, are not suffered to lay any obstacles in the way of either buyer or seller, are not known either here or in other commercial places in the Indies; but a certain duty is to be paid to government on all commodities that are sent from the ship, and sold on shore. And this duty was now farmed out to a company of Chinese, who, in a decent and becoming manner, searched the larger chests, but let trunks and chests with clothes pass untouched.’ This almost contemporary drawing of the government in Batavia, circa 1779-85, gives a glimpse into the powerful colonial administrative centre, which Thunberg experienced during his stopover. | Drawing by the artist Jan Brandes (1743-1808). (Courtesy: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. NG-1985-7-3-145).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/1-jan-brandes-batavia-800x577.jpg) When arriving in Batavia [today Jakarta] in May 1775, the naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) onboard a Dutch East Company ship, made extensive observations of all sorts of everyday matters in his travel journal. For instance, his clothes and other luggage were briefly mentioned in connection to the customhouses and tolls: ‘Institutions which, in countries where commerce is expected to flourish, are not suffered to lay any obstacles in the way of either buyer or seller, are not known either here or in other commercial places in the Indies; but a certain duty is to be paid to government on all commodities that are sent from the ship, and sold on shore. And this duty was now farmed out to a company of Chinese, who, in a decent and becoming manner, searched the larger chests, but let trunks and chests with clothes pass untouched.’ This almost contemporary drawing of the government in Batavia, circa 1779-85, gives a glimpse into the powerful colonial administrative centre, which Thunberg experienced during his stopover. | Drawing by the artist Jan Brandes (1743-1808). (Courtesy: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. NG-1985-7-3-145).

When arriving in Batavia [today Jakarta] in May 1775, the naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) onboard a Dutch East Company ship, made extensive observations of all sorts of everyday matters in his travel journal. For instance, his clothes and other luggage were briefly mentioned in connection to the customhouses and tolls: ‘Institutions which, in countries where commerce is expected to flourish, are not suffered to lay any obstacles in the way of either buyer or seller, are not known either here or in other commercial places in the Indies; but a certain duty is to be paid to government on all commodities that are sent from the ship, and sold on shore. And this duty was now farmed out to a company of Chinese, who, in a decent and becoming manner, searched the larger chests, but let trunks and chests with clothes pass untouched.’ This almost contemporary drawing of the government in Batavia, circa 1779-85, gives a glimpse into the powerful colonial administrative centre, which Thunberg experienced during his stopover. | Drawing by the artist Jan Brandes (1743-1808). (Courtesy: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. NG-1985-7-3-145).The smuggling of textiles appears chiefly to have been a problem in countries with restrictive rules of varying kinds during the 18th century, such as strict customs and excise duties, border controls, and stringent sumptuary regulations. In such places, varying degrees of trade with prohibited wares occurred, but to what extent is often unknown, as the information is both sporadic and unreliable. Sweden’s stringent bans during the Age of Liberty is one example. Due to demand for certain goods, the trade found alternative ways, which resulted in extensive smuggling. On his return journey from Spitsbergen for instance, the naturalist Anton Rolandsson Martin’s (1729-1786) autobiography uncovers an unusually detailed story of shirts of ‘brown holland’ being sold by a young itinerant pedlar to passengers on board a ship between Ystad and Stockholm in 1758 in order to avoid the excise duties in Stockholm. The illicit trade was uncovered, and the goods impounded. Records still extant show that Sweden’s strict import bans on textiles of all kinds appeared most obviously in the 1760s, particularly due to the elaborate regulation of 1766, Kongl. Maj:ts Nådige Förordning Emot Yppighet och Öfwerflöd (His Majesty’s Directive against Luxuriance and Superfluity), where the laws on sumptuousness and excess described how the use of silk fabrics and other textile luxury materials was to be restricted. But that did by no means guarantee that it was the exact truth, particularly with the smuggling of fabric in mind, which is likely to have increased in scope at that time.

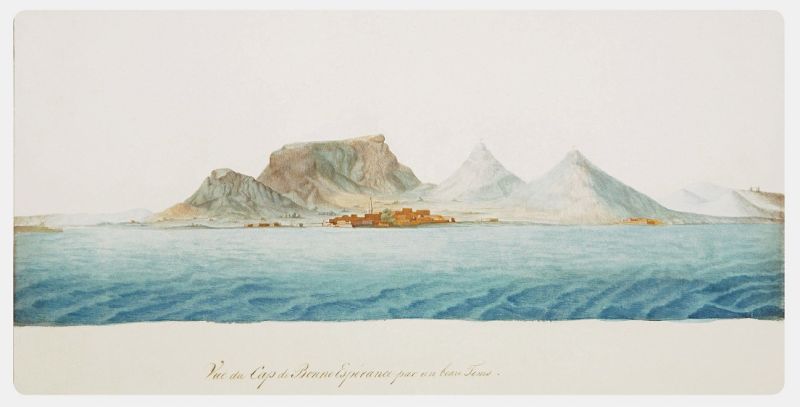

The Dutch East India Company had their own restrictive rules too, which Carl Peter Thunberg noted at the Cape in April/May 1778 – after almost eight years abroad on three continents. The crew was allowed to trade in certain commodities, but the risk of contraband was great as the Company itself had the monopoly on most desirable articles. He wrote: ‘Fine Chintzes, and Cottons, Spices, and certain other commodities, which the Company alone deals in…’. Contraband via the East India trade was generally very complex, but the information is scarce within the extensive written sources left by Carl Linnaeus and his apostles. | Here the Cape as seen from the sea, illustration made by François Le Vaillant (1753-1824) in the 1780s. (Courtesy: The Library of Parliament, South Africa. Public Domain).

The Dutch East India Company had their own restrictive rules too, which Carl Peter Thunberg noted at the Cape in April/May 1778 – after almost eight years abroad on three continents. The crew was allowed to trade in certain commodities, but the risk of contraband was great as the Company itself had the monopoly on most desirable articles. He wrote: ‘Fine Chintzes, and Cottons, Spices, and certain other commodities, which the Company alone deals in…’. Contraband via the East India trade was generally very complex, but the information is scarce within the extensive written sources left by Carl Linnaeus and his apostles. | Here the Cape as seen from the sea, illustration made by François Le Vaillant (1753-1824) in the 1780s. (Courtesy: The Library of Parliament, South Africa. Public Domain).Smuggling was also described by Thunberg during his time in Japan in the 1770s, due to that popular prohibited goods were carried to and from the ships in the port of Nagasaki. For that reason, the Dutch captain was dressed in a large blue coat of silk, decorated with silver lace and a cushion sewn in at the front. The great use they made of that elegant and loose coat was described as follows in August 1775.

- ‘This coat has for many years past been used for the purpose of smuggling prohibited wares into the country, as the chief and the captain of the ship were the only persons who were exempted from being searched. The captain generally made three trips in this coat every day from the ship to the Factory, and as frequently so loaded with goods, that when he went ashore, he was obliged to be supported by two sailors, one under each arm. By these means the captain derived a considerable profit annually from the other officers, whose wares he carried in and out, together with his own, for ready money, which might amount to several thousand Rixdollars.’

But the Dutch were discovered by the Japanese officers and the lucrative trade came to an inglorious end. The bans even reached all the way to Batavia, which is evident in Thunberg's journal, which also mentioned the strict controls of chests and luggage on the way to Japan.

![Frequent controls of Carl Peter Thunberg’s luggage became even stricter and more time-consuming during the stay in Japan, particularly linked to contraband and goods which the Europeans desired. One such event was mentioned in June 1776 under the title ‘The nature and properties of the country’: ‘The norimons and the rest of the baggage, as also we ourselves, were strictly searched. It is true, I had no contraband articles to hide; but as to the scarce coins and maps, which I with great pains and difficulty had procured, I was unwilling either to lose them, or, by their means, bring any man into difficulties. Therefore, after having put the maps amongst other papers, and covered the thick coins over with plaster, and hid the thinner pieces in my shoes, I arrived, with the rest of our company, safe in the factory on the 30th of June…’. All maps were prohibited for exportation from Japan – but even so he hid and brought back these mentioned maps to Uppsala, where they are still kept in the university library up to this day. This illustrated example depicts Nagasaki with Dutch and Chinese ships in the harbour and the fan-shaped island Dezima, which was designated to the foreign traders and visitors. It is probable that these four maps are the total number of Japanese maps (dated to 1772-76) of woodblock print on paper which he transported back home among his collections in 1779, the other three showing Edo [today Tokyo], Kyoto and Osaka. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. No: 91727/Alvin. Public Domain).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/3-nagasaki-1770s-thunberg-copy-800x593.jpg) Frequent controls of Carl Peter Thunberg’s luggage became even stricter and more time-consuming during the stay in Japan, particularly linked to contraband and goods which the Europeans desired. One such event was mentioned in June 1776 under the title ‘The nature and properties of the country’: ‘The norimons and the rest of the baggage, as also we ourselves, were strictly searched. It is true, I had no contraband articles to hide; but as to the scarce coins and maps, which I with great pains and difficulty had procured, I was unwilling either to lose them, or, by their means, bring any man into difficulties. Therefore, after having put the maps amongst other papers, and covered the thick coins over with plaster, and hid the thinner pieces in my shoes, I arrived, with the rest of our company, safe in the factory on the 30th of June…’. All maps were prohibited for exportation from Japan – but even so he hid and brought back these mentioned maps to Uppsala, where they are still kept in the university library up to this day. This illustrated example depicts Nagasaki with Dutch and Chinese ships in the harbour and the fan-shaped island Dezima, which was designated to the foreign traders and visitors. It is probable that these four maps are the total number of Japanese maps (dated to 1772-76) of woodblock print on paper which he transported back home among his collections in 1779, the other three showing Edo [today Tokyo], Kyoto and Osaka. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. No: 91727/Alvin. Public Domain).

Frequent controls of Carl Peter Thunberg’s luggage became even stricter and more time-consuming during the stay in Japan, particularly linked to contraband and goods which the Europeans desired. One such event was mentioned in June 1776 under the title ‘The nature and properties of the country’: ‘The norimons and the rest of the baggage, as also we ourselves, were strictly searched. It is true, I had no contraband articles to hide; but as to the scarce coins and maps, which I with great pains and difficulty had procured, I was unwilling either to lose them, or, by their means, bring any man into difficulties. Therefore, after having put the maps amongst other papers, and covered the thick coins over with plaster, and hid the thinner pieces in my shoes, I arrived, with the rest of our company, safe in the factory on the 30th of June…’. All maps were prohibited for exportation from Japan – but even so he hid and brought back these mentioned maps to Uppsala, where they are still kept in the university library up to this day. This illustrated example depicts Nagasaki with Dutch and Chinese ships in the harbour and the fan-shaped island Dezima, which was designated to the foreign traders and visitors. It is probable that these four maps are the total number of Japanese maps (dated to 1772-76) of woodblock print on paper which he transported back home among his collections in 1779, the other three showing Edo [today Tokyo], Kyoto and Osaka. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, Sweden. No: 91727/Alvin. Public Domain).Theft or dishonesty to do with clothes was mentioned on a few occasions, but seems nonetheless to have caused the travellers only limited inconvenience as they saw it at the time. Daniel Solander’s (1733-1782) companion, Joseph Banks (1743-1820), wrote that they had had problems with theft of clothing in the Pacific. Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) made a similar observation in North America in 1749 where the indigenous inhabitants stole linen shirts from the settlers; in both cases the reason was thought to lie in the fact that the people did not have any woven fabrics of their own, thus making European garments much sought after. Peter Forsskål (1732-1763) wrote in a letter one year prior to his death to Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) that some of his clothes had been stolen by robbers in the Egyptian countryside. During his time in China in the early 1750s, Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) often felt cheated by the Chinese, as they, according to him, used sub-standard measuring-rods when measuring out cloth. Carl Peter Thunberg, on the other hand, described how the Japanese tried to prevent theft or mistaken exchanges of nightgowns in Japan by having each garment marked with the owner’s symbol or name.

-664x663.jpg) This beautiful piece of Indian chintz was a typical quality, desirable for smuggling in several European countries, like in England, where the so-called Calico Acts banned import of most cottons including some sort of ornamentation from circa 1700-1774 (modified rules over these years). However, one thought is that it was probably not the case for this preserved piece of fabric, as the extensive sumptuary laws of the 1750s and 1760s in Sweden had multiple restrictions on silks, but these repeated bans did not to the same degree affect printed cottons brought back in private trade. This particular fabric is believed to have been taken to Sweden in the 1760s by Captain Mathias Holmers (1712-1799) on a Swedish East India Company ship. The depicted example is one of three identical fabric pieces kept in the Nordic Museum collection. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm. No: NM.0230821A-C).

This beautiful piece of Indian chintz was a typical quality, desirable for smuggling in several European countries, like in England, where the so-called Calico Acts banned import of most cottons including some sort of ornamentation from circa 1700-1774 (modified rules over these years). However, one thought is that it was probably not the case for this preserved piece of fabric, as the extensive sumptuary laws of the 1750s and 1760s in Sweden had multiple restrictions on silks, but these repeated bans did not to the same degree affect printed cottons brought back in private trade. This particular fabric is believed to have been taken to Sweden in the 1760s by Captain Mathias Holmers (1712-1799) on a Swedish East India Company ship. The depicted example is one of three identical fabric pieces kept in the Nordic Museum collection. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm. No: NM.0230821A-C).![Several of Carl Linnaeus’ former students travelled with the Swedish East India Company, one of them was the earlier mentioned Pehr Osbeck, as a ship’s chaplain-cum-naturalist. Interestingly, his travel journal details a comprehensive list of silk fabrics ordered by the Company during the stopover in Canton [today Guangzhou] 1751-52, to be transported back to Göteborg. The circumstances for import of silks to Sweden was different just three years later – by now even plain silks were not allowed to be imported (‘raw silk’ excluded, as it was a necessary raw material for the Swedish silk weaving manufacturers), which explains the absence of imported silk fabrics in this 1755 year sales catalogue. A reality, which almost instantly increased the attraction of smuggling of such goods, due the ongoing great demand of Chinese silks. However, among tea, porcelain, arrack and other goods – ‘Silk & Cotton Ware for Exportation’ was listed in the right-hand bottom corner of this illustrated page. That is to say, that these textiles had to be reexported before entering the Swedish market. An import ban of one sought-after merchandise, secondarily favoured another, which in this case came to be plain cotton qualities, not affected by the import ban. | See a translation below, including textiles carried on these two East India ships from Canton to Göteborg in Sweden, to be sold in the summer of 1755, with the number of buyers and my summaries from the catalogue within square brackets. (Courtesy: ‘Kommerskollegiet’s archive…The Swedish East India Company – sales catalogue 1755, ’Friedrich Adolph & Enigheten’, final page).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/5-east-india-trade-1755-800x637.jpg) Several of Carl Linnaeus’ former students travelled with the Swedish East India Company, one of them was the earlier mentioned Pehr Osbeck, as a ship’s chaplain-cum-naturalist. Interestingly, his travel journal details a comprehensive list of silk fabrics ordered by the Company during the stopover in Canton [today Guangzhou] 1751-52, to be transported back to Göteborg. The circumstances for import of silks to Sweden was different just three years later – by now even plain silks were not allowed to be imported (‘raw silk’ excluded, as it was a necessary raw material for the Swedish silk weaving manufacturers), which explains the absence of imported silk fabrics in this 1755 year sales catalogue. A reality, which almost instantly increased the attraction of smuggling of such goods, due the ongoing great demand of Chinese silks. However, among tea, porcelain, arrack and other goods – ‘Silk & Cotton Ware for Exportation’ was listed in the right-hand bottom corner of this illustrated page. That is to say, that these textiles had to be reexported before entering the Swedish market. An import ban of one sought-after merchandise, secondarily favoured another, which in this case came to be plain cotton qualities, not affected by the import ban. | See a translation below, including textiles carried on these two East India ships from Canton to Göteborg in Sweden, to be sold in the summer of 1755, with the number of buyers and my summaries from the catalogue within square brackets. (Courtesy: ‘Kommerskollegiet’s archive…The Swedish East India Company – sales catalogue 1755, ’Friedrich Adolph & Enigheten’, final page).

Several of Carl Linnaeus’ former students travelled with the Swedish East India Company, one of them was the earlier mentioned Pehr Osbeck, as a ship’s chaplain-cum-naturalist. Interestingly, his travel journal details a comprehensive list of silk fabrics ordered by the Company during the stopover in Canton [today Guangzhou] 1751-52, to be transported back to Göteborg. The circumstances for import of silks to Sweden was different just three years later – by now even plain silks were not allowed to be imported (‘raw silk’ excluded, as it was a necessary raw material for the Swedish silk weaving manufacturers), which explains the absence of imported silk fabrics in this 1755 year sales catalogue. A reality, which almost instantly increased the attraction of smuggling of such goods, due the ongoing great demand of Chinese silks. However, among tea, porcelain, arrack and other goods – ‘Silk & Cotton Ware for Exportation’ was listed in the right-hand bottom corner of this illustrated page. That is to say, that these textiles had to be reexported before entering the Swedish market. An import ban of one sought-after merchandise, secondarily favoured another, which in this case came to be plain cotton qualities, not affected by the import ban. | See a translation below, including textiles carried on these two East India ships from Canton to Göteborg in Sweden, to be sold in the summer of 1755, with the number of buyers and my summaries from the catalogue within square brackets. (Courtesy: ‘Kommerskollegiet’s archive…The Swedish East India Company – sales catalogue 1755, ’Friedrich Adolph & Enigheten’, final page). The Ship Friedrich Adolph

Return to Göteborg 24 July & 5 July 1755 – auction 4 September & following days 1755

- Raw Silk, 9 Chests, sold per/pound net. Lott. 2239-2247. [Five buyers].

- Yellow Nankeens. 6019 pieces of 9 aln length. Lot 2248-2329. [Sold in lots of 50 and 100. And a final lot of 169, whereof 20 white, 71 yellow stained, 10 ditto totally damaged. Thirteen buyers].

- Red Nankeens. 340 pieces of the same length and width. Lot 2330-2336. [Sold in lots of 50 and 40. Seven buyers]

- Cotton yarn, 560 p. sold per/pound net [1 bale circa 80 p.] Lot 2337-2343. [Sold in seven lots to three buyers].

- Cotton Goods. Lot 2398. 6 pieces of Nankeens. | Lot 2399. 1 piece of cambric 12 aln long 1 1/4 aln wide & 1 piece of cotton tabby 24 aln length 1 1/4 aln wide & 2 pieces various [All sold to one buyer].

- Silk & Cotton Ware for Exportation. Lot 2408-2413. | 7 pieces of black Paduasoy, 1 piece red ditto. | 2 pieces of Pelong |3 pieces of lining Taffetas | 2 pieces of striped Ginghams | 3 pieces of brocaded Taffeta on white ground 23 1/2 aln length, 1 1/2 aln wide | 1 piece blue Taffeta 23 1/2 aln length 1 1/2 aln wide 1 piece straw coloured ditto ditto. [Sold to three buyers who had to reexport the goods due to the fact that these textile qualities were prohibited from being sold in Sweden in 1755. Furthermore, the rules of this trade were carefully stated in the catalogue: ‘The Silk and Cotton Wares for export, will not be stamped, and therefore no stamp duty is paid. Besides, all goods that are for export will, in the custom officers’ presence, be packed, and by them with the custom seal, be sealed up, for which the buyer has to pay 8 öre Silver coins for each seal’].

Enigheten (Canton)

- The Ship Enigheten’s cargo, mostly unsold’ [it is unknown why, but in the introduction of the catalogue the following textiles were listed, included in the cargo of this ship]. 1097 p. [1 bale circa 80 p.] of raw Silk in 7 Chests. & 4016 Pieces of Yellow Nankeens.

……

To conclude, this case study has aimed to give a glimpse into the rather extensive smuggling of fabrics between the complex networks of 18th century global trade routes – and some reasons why such prohibited trade developed in some countries. Even that import ban on silks, over a period in Sweden, for instance, simultaneously favoured an increased import of cotton cloth via the East India trade. Together with a few observations on theft of textiles – which from these travellers’ perspectives seems to have been an unexpectedly minor concern – judging by in-depth studies of journals and correspondence related to Carl Linnaeus’ apostles. A group of naturalists, who visited more than fifty countries. Likewise, as an illicit trading of maps, besides in Japan, appears to have been even rarer still. Some of these multifaceted trade obstacles are evident via Carl Peter Thunberg’s in the mid-1770s, in particular on the occasion when his journal clearly stated that he had had an opportunity to purchase Japanese maps in Edo. This implies that the objects were not forbidden for a European naturalist to buy when in company with embassy officials and Japanese interpreters, but when he later exported these maps among his luggage onboard a Dutch East India Company ship, it became an illicit trade. In general though, maps and charts were frequently mentioned for practical aspects in their journals and were obviously of invaluable assistance during long-distance travels. When such a document existed over a visited area, it was advantageous for pre-planning routes to ease ongoing travels and increase one’s curiosity for the next step of the voyage alike.

This essay is linked to my earlier research about the Linnaeus Apostles, as well as part of the ongoing textile and natural history project: ’Personal belongings and collections on 18th century travels’.

Sources:

- Banks, Joseph, The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks – 1768-1771. Edited by J.C. Beaglehole, 2 vol., Sydney 1963.

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Travel journals of Anton Rolandsson Martin, Pehr Kalm, Peter Forsskål & Pehr Osbeck).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 28, 114-119, 271-273 & 420).

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textilis Essays. ’18th Century East India Textile Trade – A Study of imported Merchandise to Sweden’: No: CIV | April 4, 2019.

- Kommerskollegiet’s Archive, Riksarkivet, Stockholm: The Swedish East India Company – sales catalogue. 1755 ‘Friedrich Adolph & Enigheten’ (digitised by Warwick Digital Collections).

- Kjellberg, Sven T., Svenska Ostindiska Compagnierna 1731-1813, Malmö 1974.

- Kongl. Maj:ts Nådige Förordning, Emot Yppighet och Öfwerflöd, Stockholm 1766.

- Le Vaillant, François, Traveller in South Africa 1781 1784, 2 volumes, Cape Town 1973.

- Nordic Museum, Stockholm (DigitaltMuseum, information on online catalogue card about the origin of the Indian chintz, No: NM.0230821A-C).

- Peck, Amelia, ed., Interwoven Globe – The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, New York 2013 (Watt, M., pp. 87-88, Calico Acts).

- Söderpalm, Kristina, ed., Ostindiska Compagniet – Affärer och Föremål, Göteborgs Stadsmuseum 2003.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE