ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

SOURCES OF LIGHT AND TEXTILE MATERIALS

– Observations by 18th Century Travelling Naturalists

For a multitude of reasons, candles and lamps were repeatedly mentioned in the journals of Carl Linnaeus’ seventeen Apostles – who made natural history journeys to more than 50 countries. Primarily due to their reading or writing during dark hours, movement in the darkness, observations of ceremonial traditions, how candles were produced etc. Whilst lanterns, torches and fires were other sources of light in these descriptions dating from the 1740s to 1790s. This essay will focus on such attention to details when being associated with a good night’s sleep in comfortable beds, Tahitian bark cloths, the preference of cotton wicks and other textile perspectives. Observations, which give enlightening information about everyday life in Paris, London, Philadelphia, Canton (Guangzhou), Nagasaki and other geographical areas visited by seven of these travelling naturalists.

One may imagine that the naturalist Pehr Kalm’s (1716-1779) clothing and facial features in Grimstad along the Norwegian coast, were illuminated in a similar way like for the young woman on this engraving dating from 1772. In the travel journal on 8 January 1747, Kalm wrote: ’I took the candle from the room and held one of these luminous pieces close to a book, when I could clearly read the entire title page of Wallerius Mineralogie.’ (Courtesy: Wellcome Library no. 33671i, Mezzotint by P. Dawe after J. Foldsone. Public Domain).

One may imagine that the naturalist Pehr Kalm’s (1716-1779) clothing and facial features in Grimstad along the Norwegian coast, were illuminated in a similar way like for the young woman on this engraving dating from 1772. In the travel journal on 8 January 1747, Kalm wrote: ’I took the candle from the room and held one of these luminous pieces close to a book, when I could clearly read the entire title page of Wallerius Mineralogie.’ (Courtesy: Wellcome Library no. 33671i, Mezzotint by P. Dawe after J. Foldsone. Public Domain).Pehr Kalm’s travel journal reveals further information on the subject of the Norwegian coastal communities, due to his general interest and curiosity as well as professional aims on his way towards the North American colonies – via England – to report about learned natural knowledge from all possible angles. For instance, on 17 December 1747, he noted from Arendal:

- ‘Lamps were used almost everywhere here along the coast for illumination in the evenings instead of candles; for fuel in the lamp most of those who could afford it used rape-oil, which was brought here from Holland, as this did not reek like train-oil; but those who could not afford that or were unable to acquire rape-oil used train-oil as fuel in the lamps, although it did reek quite strongly; for wicks they used cotton wicks almost everywhere. The lamp itself was made of tin-plate, in shape almost like a tankard, though very small, with one [spout] or else two spouts opposite each other, according to how brightly one wanted it to shine; in this spout lay the cotton wick which, as it burned at the end, drew oil to itself from the lamp through the spout;…’

Another of Pehr Kalm’s observations connected to sources of light and textiles – in this case a multitude of burning lamps and the finely dressed visitors – may instead be gleaned from his lengthy stay in London. On 9 June 1748 in particular, when he made notes about the pleasure garden Vauxhall: ’…No man or woman is allowed into the garden here unless they pay a shilling on entry; one is then free to buy something to eat and drink or not; and one can listen to the music, stroll around, see and be seen etc. without any further expenditure; as soon as it begins to become somewhat dusky, lamps are lit everywhere, of which there are a great number here in the garden, and then burn until a little after 10, when all the guests have left, which happens around 10 o’cl., when the music and song cease. One sees a great variety here of statues and ornaments such as are used in gardens…’ His observation is an enlightening comparison to this almost contemporary illustration (c. 1750-60) from Vauxhall Garden, where lamps are clearly visible along the Grand Walk and in the open-air areas in the building to the right alike. (Courtesy: Garden Museum, Ref: 2011.096. Collection no. 2011.096. Watercolour by J.S. Muller c.1715-1792).

Another of Pehr Kalm’s observations connected to sources of light and textiles – in this case a multitude of burning lamps and the finely dressed visitors – may instead be gleaned from his lengthy stay in London. On 9 June 1748 in particular, when he made notes about the pleasure garden Vauxhall: ’…No man or woman is allowed into the garden here unless they pay a shilling on entry; one is then free to buy something to eat and drink or not; and one can listen to the music, stroll around, see and be seen etc. without any further expenditure; as soon as it begins to become somewhat dusky, lamps are lit everywhere, of which there are a great number here in the garden, and then burn until a little after 10, when all the guests have left, which happens around 10 o’cl., when the music and song cease. One sees a great variety here of statues and ornaments such as are used in gardens…’ His observation is an enlightening comparison to this almost contemporary illustration (c. 1750-60) from Vauxhall Garden, where lamps are clearly visible along the Grand Walk and in the open-air areas in the building to the right alike. (Courtesy: Garden Museum, Ref: 2011.096. Collection no. 2011.096. Watercolour by J.S. Muller c.1715-1792).A few months later, when arriving in Philadelphia by ship from London, Pehr Kalm’s first destination in North America, more practical matters were related to himself and his assistant’s daily life. Kalm reported, for instance, the following in his journal on 16 September 1748:

- ‘At night I took up my lodging with a grocer who was a Quaker, and I met with very good honest people in this house, such as most people of this profession appeared to me, I and my [assistant Lars] Yungstraem, the companion of my voyage, had a room, candles, beds, attendance, and three meals a day, if we chose to have so many, for twenty shillings per week in Pennsylvania currency. But wood, washing and wine, if required, were to be paid for besides.’

This oil on canvas by the Swedish artist Pehr Hilleström (c. 1770s-80s) of ‘A Woman Picking Fleas by Candlelight’ has an interesting resemblance – of such a global health issue for mankind over time – with journal notes of the naturalist Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805). During his stay in Canton (Guangzhou), when working as a ship’s chaplain-cum-naturalist on a Swedish East India Company ship from 1750 to 1752, he wrote in September 1751. ‘You are obliged to draw your curtains quite close, to keep out Mosquitoes, a species of gnats, which is very troublesome at night; and whose sting is sometimes the cause of incurable complaints. Hence the influence of different climates appears: for in our country the bite of a flea, and the sting of a gnat, are reckoned equal; but it is quite otherwise in China, though these gnats are the same with ours.’ (Courtesy: National Museum, Stockholm, NM 6756, Wikimedia Commons).

This oil on canvas by the Swedish artist Pehr Hilleström (c. 1770s-80s) of ‘A Woman Picking Fleas by Candlelight’ has an interesting resemblance – of such a global health issue for mankind over time – with journal notes of the naturalist Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805). During his stay in Canton (Guangzhou), when working as a ship’s chaplain-cum-naturalist on a Swedish East India Company ship from 1750 to 1752, he wrote in September 1751. ‘You are obliged to draw your curtains quite close, to keep out Mosquitoes, a species of gnats, which is very troublesome at night; and whose sting is sometimes the cause of incurable complaints. Hence the influence of different climates appears: for in our country the bite of a flea, and the sting of a gnat, are reckoned equal; but it is quite otherwise in China, though these gnats are the same with ours.’ (Courtesy: National Museum, Stockholm, NM 6756, Wikimedia Commons).It was not only Pehr Osbeck’s detailed personal experiences of the troublesome mosquitoes and the necessity to use curtains or nets in the hot climate, which were thoroughly listed in his descriptions of Canton. During his first months (autumn 1751) in the trading city, lamps were just as important for the smooth running of everyday life. He noted for instance that in each room was a lamp, fastened to the roof by a long rope, but they also ‘have both white wax candles and others, which they call Lapp-tiock.’ A fine gauzy fabric was additionally used for lanterns: ’Behind this the yard is quite open in front, but on the sides are rooms both above and below. In the side roofs are here and there some lanterns of painted gauze, in some of which they burn lamps at night.’ Such gauzy painted fabrics were probably either made of cotton or silk.

During the same decade in another part of the world, Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) apostle Daniel Rolander (1723 or 1725-1793) visited Suriname. His extensive journal, originally written in Latin, reveals some informative details on sources of light, textiles and insects alike. The arrival and the early days in the country were particularly difficult for Rolander: a combination of heat, humidity, strong smells, insects buzzing, “dangerous animals”, and a general feeling of uneasiness. Sleeping and getting some night rest was also extremely trying, at the same time as he had to get used to sleeping in a hammock. Yet that berth was thought considerably more comfortable in the constant heat than a warm bed. The hammock could also have the advantage of making it more difficult for crawling insects to surprise the sleeper, though it was no guarantee as they might drop down from the ceiling, which is mentioned on 26 June 1755. ‘About midnight, a short time before I had gone to sleep, I felt a small animal moving on my foot. I immediately grabbed a lit candle, and having carefully and gradually withdrawn the hammock from my foot, I discovered a Scorpio Americanus slowly moving across my foot. My hair stood on end and my limbs turned to ice, but nevertheless I kept my foot still until this unpleasant insect had gone past it and into the hammock.’ Rolander escaped unscathed from the incident and continued to sleep in the hammock. He also noted the significance of that sleeping arrangement in other contexts, mainly to do with what materials were used and who manufactured them. On a visit to an indigenous people, the following brief and illuminating sentence was entered on 4 August 1755: ‘At night he slept wrapped in the same hammock, which was woven, as usual, out of cotton and coloured red.’ Some weeks later – 26 September in 1755 – Rolander also combined candlelight with his handkerchief to catch crickets and study their acclimatisation to light as part of his observations of insects.

This coloured print, ‘The Marriage Ceremony’, probably dated 1768, displays great similarities with the naturalist and physician Carl Peter Thunberg’s (1743-1828) journal notes of the dress, ceremonies, lanterns etc of the prosperous Japanese women and men. Particularly striking in his information about Japan in 1776: ‘The people of distinction and those that are rich, have a great number of attendants, and every one, in general, has some attendants in his house, to wait upon him, and when he goes abroad, to carry his cloak, shoes, umbrella, lantern, and other things that he may want of a similar nature.’ (Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. No. JP875. Polychrome woodblock print; ink and colour on paper, by Suzuki Harunobu. Online collection, Public Domain).

This coloured print, ‘The Marriage Ceremony’, probably dated 1768, displays great similarities with the naturalist and physician Carl Peter Thunberg’s (1743-1828) journal notes of the dress, ceremonies, lanterns etc of the prosperous Japanese women and men. Particularly striking in his information about Japan in 1776: ‘The people of distinction and those that are rich, have a great number of attendants, and every one, in general, has some attendants in his house, to wait upon him, and when he goes abroad, to carry his cloak, shoes, umbrella, lantern, and other things that he may want of a similar nature.’ (Courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. No. JP875. Polychrome woodblock print; ink and colour on paper, by Suzuki Harunobu. Online collection, Public Domain). Additionally, Thunberg noticed the following traditions linked to light and textiles on his journey to the Japanese Court in 1776:

- ‘Besides those articles which had been sent from Nagasaki by water, were carried partly on horseback and partly by porters on foot, our small chests of clothes, lanterns to use in the dark, as stock of wine, ale, and other liquors, for our daily consumption, and a Japanese apparatus for tea, in which we could boil water while we were on the road.’

His observations were truly reflecting global cultures, often with admiration or curiosity in visited areas – stretching over a nine-year period from 1770 to 1779 – starting from Uppsala in Sweden passing through or staying for longer periods in Denmark, Holland, France, the Cape area (South Africa), Java, Japan, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), England and the German-speaking lands (Germany). Already during his circa half-year stay in Paris, notes about fine textiles and the significance of candlelight in ceremonies were included in his extensive journal. For instance, on 2 December 1770: ’The procession was performed at the Hotel Dieu, that is usually made there on the first Sunday of every month. The friars and nuns, who nurse the sick, were on this occasion clad in white, with black cloaks, and carried long candles in their hands.’ Whilst on 30 May in 1771, during his time in the French capital he described annually recurring festivities, called the feast of the sacraments (Fête-Dieu), all churches arranged parades, music, flower arrangements and candles. An important part was that along many streets, people hung ‘tapestry of all sorts’ as high up as the second floor. The walls of the houses being decorated with colourful weavings must have formed a part of the spectacle itself. At the same time, the owners had the opportunity to show off their textile wealth to neighbours and other passers-by.

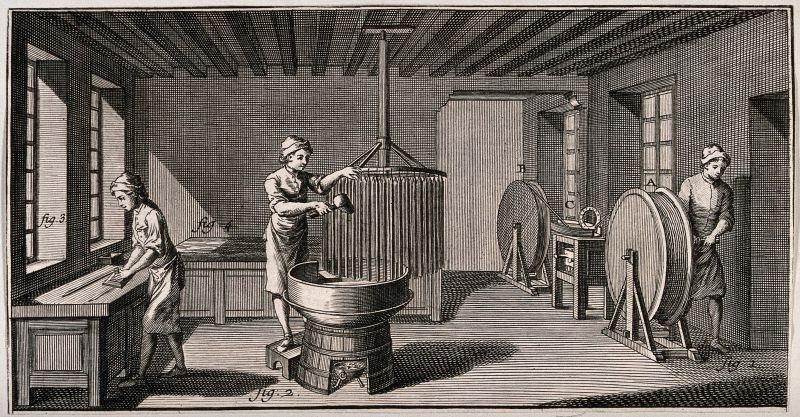

This almost contemporary French etching of candle making, may also be compared to Thunberg’s observations in Paris – especially with the workman in the middle making ‘long candles’ just as described in his journal. The etching was originally published as a plate in ‘Encyclopédie ... recueil de planches, sur les sciences …’, vol. 25 in Paris 1768, by D. Diderot and J. le R. d’Alembert. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library no. 37464i. Public Domain).

This almost contemporary French etching of candle making, may also be compared to Thunberg’s observations in Paris – especially with the workman in the middle making ‘long candles’ just as described in his journal. The etching was originally published as a plate in ‘Encyclopédie ... recueil de planches, sur les sciences …’, vol. 25 in Paris 1768, by D. Diderot and J. le R. d’Alembert. (Courtesy: Wellcome Library no. 37464i. Public Domain).Three of Carl Linnaeus’ later students who travelled during his old age and even after his lifetime, reflected on some further connections between light and textiles – seen in the context of their European perspective. Anders Sparrman (1748-1820), when he worked as an assistant botanist on James Cook’s (1728-1779) second voyage, noted in his journal when the ship lay at anchor off the island of Mallicolo how cloths caused problems. The danger arose because of smoke emerging from below deck; everybody seemed to fear the worst, that is to say, that the gunpowder store would catch fire and explode. Relieved, Sparrman wrote on 1 August 1774: ‘Fortunately, the evil still only extended to a candle that had fallen on top of a cloth jacket and Tahitian bark cloth down in the storeroom where it was easily extinguished’. The burning cloths were quenched without difficulty, and order on the ship was restored. Exactly one year later in another part of the world, Göran Rothman (1739-1778) described how he and his companions during fieldwork managed to have an evening meal and sleep in reasonable comfort outside Tripoli in Libya on 1 August 1775: ‘We took now an earth den, made us a lamp of the oil which was left from the dinner in a bottle of the oil and vinegar mixture for the salad. And as we were well armed and had good watch both by the cannons in the ship and in the rooms outside, we lay down on the floor to sleep and made a bed of sails, cloth and clothes.’ Whilst Adam Afzelius (1750-1837), as the final of these travelling naturalists outside Europe, on 12 June in 1795 from a field trip in Sierra Leone made notes about candles, clothes and a good night’s sleep:

- ‘But after a wax candle being lighted, we retreated to the piazza, whereas it was cool and refreshing, we spent a comfortable evening in drinking good water as they had, and in gossiping with the women and children to 9 o’clock, when we went to bed, the Dr. and Mr. G. going to another house in the town, where a room with a bed in was prepared for their reception, and Mr. W. and I remaining in Jemmy Queen’s own house, where we had a chamber with a good bed, which is very uncommon among the Natives. Nevertheless, we rather preferred to sleep on the bed cover in our own clothes, than to undress. We only took off our coats and shoes.’

Sources:

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Journals published in; Vol. three: Pehr Kalm & Daniel Rolander. Vol. Four: Göran Rothman & Adam Afzelius).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 70, 250-51 & 357).

- Osbeck, Peter [Pehr], A Voyage to China and the East Indies, 2 vol., London 1771.

- Sparrman, Anders, Resa omkring Jordklotet, I sällskap med Kapit. J. Cook och Hrr Forster. Åren 1772, 73, 74 och 1775…Stockholm 1818.

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE