ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

TAPESTRIES, SILK AND GARDENS

– A Swedish Naturalist in Paris from 1770 to 1771

The naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg’s (1743-1828) journey started in August 1770 from Uppsala when his studies were completed – among other places, he visited Amsterdam, Paris, the Cape, Java, Japan and London – to return home after nine years in 1779. The aim of this essay, however, is to look closer at his seven months in Paris from where his travel journal gives references to visited hospitals, libraries, churches, gardens and educational institutions. Textile observations were also entered in his journal, in particular, that he was granted a unique insight into the Manufacture des Gobelins in Paris 1771, where he was impressed by the splendour and design of the tapestries and the weavers’ technical skills. Preserved interior furnishing from this famous textile manufacturer and artwork of the metropolitan city will further enlighten his visit. Historically, Thunberg’s stay in Paris coincided with the final years of the reign of Louis XV and a mere 18 years before the Revolution.

‘A View from the Point Neuf’ in 1763, or just a few years prior to Carl Peter Thunberg’s stay in Paris. This must have been a familiar sight for him, even if his references to fashionable dress or everyday clothing worn by various strata of society in the city were mentioned in passing only, like, for instance, in his journal on 24 December 1770: ‘very small muffs were worn here by both sexes.' On the same day, he also reflected on reality, not visible in this glamorous depiction: ‘The water of the Seine, that runs through the city, is unwholesome, especially to strangers newly arrived. From the chalk it holds in solution, it has a milky colour and is apt to occasion diarrhoea’. |Oil on canvas by Nicolas-Jean-Baptiste Raguenet (1715-1793). (Courtesy: J. Paul Getty Museum. No: 71.PA.26. Wikimedia Commons).

‘A View from the Point Neuf’ in 1763, or just a few years prior to Carl Peter Thunberg’s stay in Paris. This must have been a familiar sight for him, even if his references to fashionable dress or everyday clothing worn by various strata of society in the city were mentioned in passing only, like, for instance, in his journal on 24 December 1770: ‘very small muffs were worn here by both sexes.' On the same day, he also reflected on reality, not visible in this glamorous depiction: ‘The water of the Seine, that runs through the city, is unwholesome, especially to strangers newly arrived. From the chalk it holds in solution, it has a milky colour and is apt to occasion diarrhoea’. |Oil on canvas by Nicolas-Jean-Baptiste Raguenet (1715-1793). (Courtesy: J. Paul Getty Museum. No: 71.PA.26. Wikimedia Commons).Like many other young Swedish men of means during the 18th century, Carl Peter Thunberg aimed to visit Paris to increase his knowledge of science and art. In contrast to most such travellers, he was not a wealthy man, but a few enlightening notes in his journal about preparations when still in Uppsala at the outset of his journey in August 1770 reveal how it was financed.

- ‘After having spent nine years at the University of Upsal, the most respectable in Sweden, and passed the usual examinations for taking the Degree of Doctor of Physic, I obtained from the Academical, Consistory the Kohrean Pension for travelling, which, in the space of three years, amounts to 3800 Daler in copper coins, and with my own little stock, enabled me to undertake a journey to Paris, with a view to my farther improvement in Medicine, Surgery, and Natural History.’

-664x636.jpg) Carl Peter Thunberg was portrayed in oil on canvas, etchings, copperplates and several of them even in various copies, but not as a young man during his stay in Paris. This example, in profile with the decoration of a knight of the Order of the Wasa, gives a good impression of him, as seen in a German etching from 1799. It may be assumed, however, that this portrayal initially dates from the mid-1780s when he was around 40 years old. (From: ‘Journal für die Botanik’, Vol. 1., Göttingen 1799). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.

Carl Peter Thunberg was portrayed in oil on canvas, etchings, copperplates and several of them even in various copies, but not as a young man during his stay in Paris. This example, in profile with the decoration of a knight of the Order of the Wasa, gives a good impression of him, as seen in a German etching from 1799. It may be assumed, however, that this portrayal initially dates from the mid-1780s when he was around 40 years old. (From: ‘Journal für die Botanik’, Vol. 1., Göttingen 1799). Photo: The IK Foundation, London.On the 1st of December 1770, Thunberg arrived in Paris in the morning, where his luggage was unloaded and searched in the inn yard, according to his journal. He took an apartment in the neighbourhood to hold his baggage until it became possible to get lodging nearer to the colleges and hospitals in the city. Over the almost seven-month stay in Paris, he made several textile notes – among other areas of his interest – which provide an insight into the lives of the prosperous Parisians of the pre-revolutionary period, having himself lived in such pleasant circumstances while in the city. During a visit to L’École de Chirurgie in February 1771, he was allowed into the lecture theatre. A formal and solemn atmosphere reigned in this place; the teachers’ dress consisted of black coats decorated with white ribbons. The chairs were covered in ‘velvet and galloons’, an exclusive material combined with woven ribbons of gold and/or silver, reinforcing the sense of dignity. The best types of velvet would at the time have been mainly of Italian or domestic French origin and, due to its slow process of production, extremely costly to buy. At the time of Thunberg’s visit to France, silk production was nearing its zenith at Lyon, where contemporary records, as well as modern research, show that there were about 18,000 looms active in the city in the 1780s, two-thirds of which were occupied weaving the most complex designs of silk and velvet cloth. Those types of cloth were mainly used for clothes, but also had a given market as exclusive upholstery or furnishing fabrics and other interior textiles.

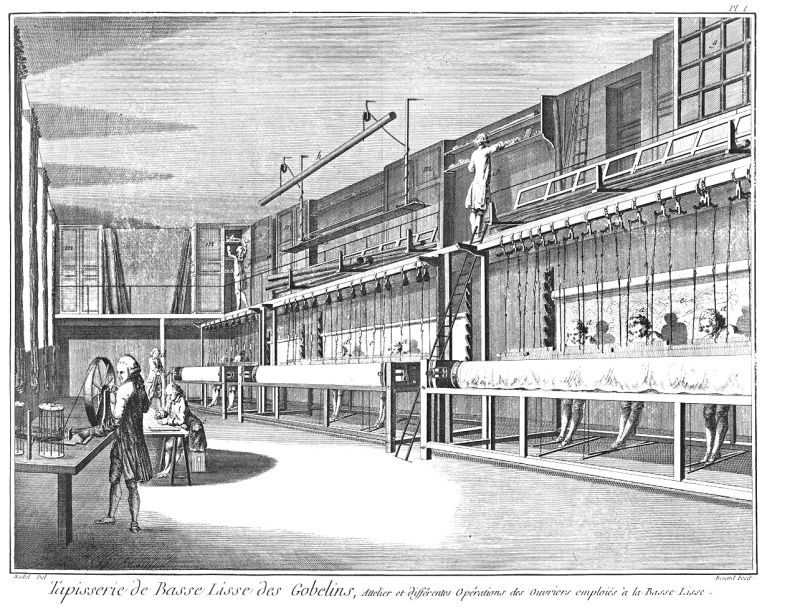

The French reference work, Encyclopédie, published continuously over more than twenty years in the spirit of the Enlightenment, printed the volume dealing with the weaving of tapestries in Paris in 1771; of interest here because Thunberg visited the Manufacture des Gobelins in the same year. The book with plates includes, among many other subjects, about ten depictions of the sites of the operation along with the construction of the looms and the weaving process. The caption for the plate selected here is of the interior of the room. It reads in translation from the French: ‘Gobelin Low Warp Tapestry, Manufacture and Various Operations of the Workers Employed at the Low Warp Loom.’ (From: Diderot, Dennis ed., Encyclopédie…volume des Planches 8, (1771), Paris 1751-1772).

The French reference work, Encyclopédie, published continuously over more than twenty years in the spirit of the Enlightenment, printed the volume dealing with the weaving of tapestries in Paris in 1771; of interest here because Thunberg visited the Manufacture des Gobelins in the same year. The book with plates includes, among many other subjects, about ten depictions of the sites of the operation along with the construction of the looms and the weaving process. The caption for the plate selected here is of the interior of the room. It reads in translation from the French: ‘Gobelin Low Warp Tapestry, Manufacture and Various Operations of the Workers Employed at the Low Warp Loom.’ (From: Diderot, Dennis ed., Encyclopédie…volume des Planches 8, (1771), Paris 1751-1772). On 30 May, Paris put on annually recurring festivities called the feast of the sacraments (Fête-Dieu); all churches arranged parades, music, flower arrangements and candles. An important part was that along many streets, people hung ‘tapestry of all sorts’ as high up as the second floor. The walls of the houses being decorated with colourful weavings must have formed a part of the spectacle itself when the owners had the opportunity to show off their textile wealth to neighbours and other passers-by. Later in the day, Thunberg was given an even more costly textile show. ‘In the afternoon I saw Gobelins, or the magnificent tapestry which is manufactured here and is always publicly exhibited on this day. All the walls of the courtyard were hung with them on the insides, as well as the apartments. They represented several histories from the Bible, as well as from Ovid and other poets. The figures were full of animations.’ That manufacturer was the well-known Manufacture des Gobelins, which started in 1662. Everything was woven from the most exclusive tapestries for the royal palace Versailles and exquisite wall coverings exported to courts and noble homes in other European countries, down to more modest, coarser wall coverings for the city’s burghers. Every tapestry was woven from a drawn cartoon where the weaver’s aim was to follow the artist’s choice of colour as closely as possible. In 1771, Michel Audran was head of the technique of Haute Lisse weaving in the upright warp, whereas the Basse Lisse weaving technique with horizontal warp was managed by Jacques Neilson, information about which can be found in the book Tapisseries des Gobelins…(1855). See below for the magnificent tapestry and upholstered furniture of matching design, woven and finalised at this manufacturer during the very same year as Thunberg’s visit.

![‘Tapestry Room from Croome Court 1763-71, after a design by Robert Adam’. Information from the present owner’s museum catalogue interestingly reveals: ‘The same year [1763], the sixth earl of Coventry commissioned the tapestry hangings from Jacques Neilson's workshop at the Royal Gobelins Manufactory in Paris. Portraying scenes from classical myths symbolising the elements, the medallions are based on designs by François Boucher.’ That is to say, the same Jacques Neilson (1714-1788) referred to above in connection to Carl Peter Thunberg’s visit to the Manufacture des Gobelins in 1771.| This textile interior also includes armchairs and more wall tapestries of the same design, which are not in the picture. (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. No: 58.75.1–.22. Gift of Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 1958. Public Domain).](https://www.ikfoundation.org/uploads/image/4-dp341255-900x517.jpg) ‘Tapestry Room from Croome Court 1763-71, after a design by Robert Adam’. Information from the present owner’s museum catalogue interestingly reveals: ‘The same year [1763], the sixth earl of Coventry commissioned the tapestry hangings from Jacques Neilson's workshop at the Royal Gobelins Manufactory in Paris. Portraying scenes from classical myths symbolising the elements, the medallions are based on designs by François Boucher.’ That is to say, the same Jacques Neilson (1714-1788) referred to above in connection to Carl Peter Thunberg’s visit to the Manufacture des Gobelins in 1771.| This textile interior also includes armchairs and more wall tapestries of the same design, which are not in the picture. (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. No: 58.75.1–.22. Gift of Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 1958. Public Domain).

‘Tapestry Room from Croome Court 1763-71, after a design by Robert Adam’. Information from the present owner’s museum catalogue interestingly reveals: ‘The same year [1763], the sixth earl of Coventry commissioned the tapestry hangings from Jacques Neilson's workshop at the Royal Gobelins Manufactory in Paris. Portraying scenes from classical myths symbolising the elements, the medallions are based on designs by François Boucher.’ That is to say, the same Jacques Neilson (1714-1788) referred to above in connection to Carl Peter Thunberg’s visit to the Manufacture des Gobelins in 1771.| This textile interior also includes armchairs and more wall tapestries of the same design, which are not in the picture. (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. No: 58.75.1–.22. Gift of Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 1958. Public Domain).The substantial manufacture of luxury textiles was based on the demand from a wealthy upper class. This fact contributed to Thunberg being able to see hanging textiles of such exclusivity and magnitude. Circumstances changed drastically for the well-off in many ways during or immediately after the Revolution, while at the same time, a more tolerable and just existence was made possible for large portions of the population. For the weaving of Gobelin tapestries, it brought about a bleak period; the activity did survive after a period of stagnation, caught on again around the year 1800, but never regained its former strength.

Interestingly, another connection to the history of the Manufacture des Gobelins may be gleaned from his journal, on 15 February 1771, when he visited the botanic garden (Jardin Royal). In his detailed registration of all sorts of bushes, trees, orangeries, hothouses and the cabinet of natural history – he included ‘the common and kermes oaks (Quercus ilex, and coccifera)’. The Mediterranean tree, kermes oaks (Quercus coccifera), had foremost been planted in this botanical garden due to its long history as a food plant for the Kermes scale insect, from which the most desired red dye – crimson – was obtained. This dye was particularly requested for the dye works of the local Gobelin manufacturer for red colours, especially from the 1660s and up to the early 18th century. Carl Peter Thunberg’s journal does not explain how many such oak trees grew in this botanical garden. Still, it is likely that the dyers back then needed to add this expensive and much sought-after dye from other places in southern France when 50.000-60.000 Kermes scale insects were required to produce one kilo of dried and pulverised dye. At the time of his visit, however, it was, without doubt, the imported cochineal – from the cochineal louse Dactylopius Coccus – a South American import via Spain, which was used for crimson red by the Paris manufacturer. A dye which rapidly gained popularity due to its increasing availability in more significant quantities – clearly visible on the tapestries and furnishing illustrated above. Whilst crimson-coloured patterning on this grand scale had been impossible to weave on French tapestries before circa 1750 when the Kermes dye had been used.

‘The Château de Versailles Seen from the Gardens’ in 1779 depicted visitors in fashionable dress. A view that Thunberg also must have admired somewhat earlier in the same decade when he visited the very same garden. On 2 July 1771, his journal reads: ‘In one of the boats that run down the Seine, I took a passage to Versailles, and from thence to Trianon, for the purpose of seeing the royal botanic garden in this place, which is the most elegant of any that I have seen.’ | Pen and black ink, watercolour by Louis Nicolas de Lespinasse (1734-1808). (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. No: 67.55.20. Bequest of Susan Dwight Bliss, 1966. Public Domain).

‘The Château de Versailles Seen from the Gardens’ in 1779 depicted visitors in fashionable dress. A view that Thunberg also must have admired somewhat earlier in the same decade when he visited the very same garden. On 2 July 1771, his journal reads: ‘In one of the boats that run down the Seine, I took a passage to Versailles, and from thence to Trianon, for the purpose of seeing the royal botanic garden in this place, which is the most elegant of any that I have seen.’ | Pen and black ink, watercolour by Louis Nicolas de Lespinasse (1734-1808). (Courtesy: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. No: 67.55.20. Bequest of Susan Dwight Bliss, 1966. Public Domain).A few concluding quotes from other gardens and connected establishments visited by Thunberg give further understanding of his scientific, curious, and educational aims during his almost seven-month stay in Paris.

- ‘I viewed the convent of St. Genevieve, its library, cabinet of natural history, and fine gardens. The library is in the uppermost storey, in the form of a cross, having bookcases all around the sides, and under the windows: the doors of the bookcases are of wire-work, and secured with locks. The books are all numbered. Between each bookcase is placed a picture of some monarch or philosopher. The library is open on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, from two till five in the afternoon, and books may be borrowed from it. The cabinet of antiquities and that of natural history are contiguous to the library and contain several amphibious animals and fishes stuffed, mummies, minerals, shells, and corals, but especially a great number of antiquities, all locked up within wire-work. The garden is neat, and is prettily ornamented with box cut in different forms.’ (14 December 1770)

- ‘And while I attended the public lectures at the chirugical college (St. Côme), the medical college, or Ecole de medicine; the botanical garden, or Jardin Royal; and the lectures in natural philosophy at the college naval, I did not neglect to attend private lectures upon anatomy, surgery and midwifery.’ (24 December 1770)

- ‘Luxembourg is a fine palace, having a spacious court and garden, which, as well as the Thuilleries, is open for every person to walk in, who has not a sword on. The gallery of pictures and drawings is open every Wednesday and Saturday, from ten till one o’clock. The history of Marie de Médicis is placed on one side; and in the apartments on the other side, a great variety of other paintings. Many of the convents are large, having their courtyards, and often beautiful gardens, open to the public.’ (15 February 1771)

- ‘Here was also a small botanical garden, laid out for the cultivation of medicinal plants for the cattle, and furnished with a little hothouse. I visited the apothecary’s garden, which, though small, contains several curious plants, and has at the bottom a grove for walking in. Free admittance to this garden may be obtained for twelve livres, and about six more in gratuities to the attendants, when the gardener presents the subscriber with a catalogue, by which the plants may be found that are not yet numbered.’ (30 March 1771)

Sources:

- Coetlogon, Dennis de, An Universal History of Arts and Sciences, London 1745.

- Diderot, Dennis ed., Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, volume des Planches 8, (1771), Paris 1751-1772.

- Hansen, Lars ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, 8 Vol., London & Whitby 2007-2012 (Vol. Six C.P. Thunberg’s journal & Vol. Eight. Biography C.P. Thunberg. pp. 46-49).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (Carl Peter Thunberg’s chapter. pp. 253-282).

- Lacordaire, A. L. Tapisseries des Gobelins et de Tapis de la Savonnerie, Paris 1855. (‘Liste ’pp. 145-46).

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Online Collection: Historical information about the illustrated tapestry and upholstered furniture. no: 58.75.1–.22).

- Sandberg, Gösta, Purpur – Koschenill – Krapp, en bok om röda textilier, Stockholm 1994 (The history of Cochineal & Kermes. pp. 43-60).

- Thunberg, Carl Peter, Travels in Europe, Africa and Asia, performed between the years 1770 and 1779. vol I-IV., London 1793-1795.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE