ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

TEXTILE INDUSTRY AND URBANISATION

– A Case Study from 1850 to 1880

In 19th century Malmö, as in many other Swedish towns and cities, one of the effects of industrialisation was a rapidly increasing population – from ca 13,000 inhabitants in 1850 to circa 38,000 in 1880. This situation changed everyday life in all sorts of ways for the urban and close-by rural areas alike. The textile industry was central, including a wide range of woollen cloth factories, stocking weavers, ribbon production, spinning manufacturers etc. The aim of this essay is to take a local reflection on the new possibilities for factory owners, the consumer revolution for the middle classes, as well as the poor standard of living for the labouring individuals, often employed within the textile industries.

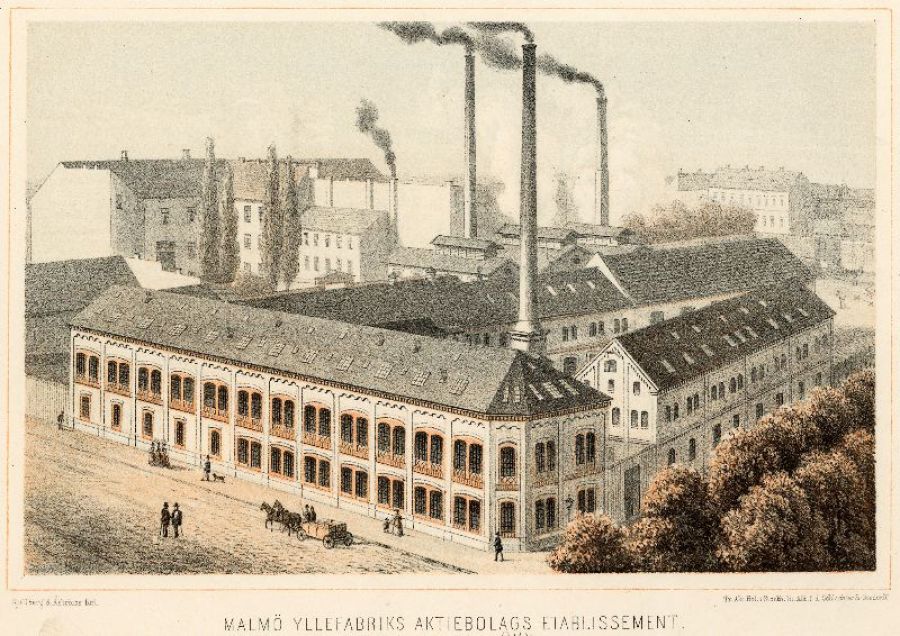

This Malmö woollen factory was established in 1861-62, here depicted about 10 years later. Initially the firm worked as a shoddy industry – weaving cloth from wasted woollens, clippings etc. At the time of this image, the workforce consisted of about two hundred employees who produced coarser cloths, corduroys and fabric for duffle coats. Lithograph after an original of unknown artist (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MM 042424).

This Malmö woollen factory was established in 1861-62, here depicted about 10 years later. Initially the firm worked as a shoddy industry – weaving cloth from wasted woollens, clippings etc. At the time of this image, the workforce consisted of about two hundred employees who produced coarser cloths, corduroys and fabric for duffle coats. Lithograph after an original of unknown artist (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MM 042424).A complex mix of circumstances resulted in the growth of textile industries in mid-19th century Sweden – as freedom of trade in 1846, increasing use of steam power, more effective looms and spinning machines, extensive cotton imports and movement of people from rural to urban areas. Even if several strata of society enjoyed the positive effects of the new innovations, it was not the case for many working-class families. The rapid movement to where industry employment was created gave rise to a shortage of housing, and many lived under extremely poor conditions. A contemporary observation gives an insight into working families’ beds: ‘The bed consisting of straw at the very bottom and both mattresses and cover feather bolsters are in use, which never are aired, and all is damp and impregnated with a stifling filthy odour, and which may be added various vermin at some even uncleaner homes’ (in translation from Swedish: Bjurling, p. 119). This was probably the reality for many within the textile industry, who worked almost 70 hours a week with poor pay.

Another local textile industry was P. Dahlström’s dye works founded in 1869. This block print of pear tree was used for printing the motif on fabrics up to the 1880s – probably on both cotton and woollen qualities. Furthermore, Malmö Museum keeps more than twenty contemporary wooden block prints once used in this particular 19th century establishment (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MM 006620:025).

Another local textile industry was P. Dahlström’s dye works founded in 1869. This block print of pear tree was used for printing the motif on fabrics up to the 1880s – probably on both cotton and woollen qualities. Furthermore, Malmö Museum keeps more than twenty contemporary wooden block prints once used in this particular 19th century establishment (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MM 006620:025).  This view of Malmö from 1857 was sketched from the nearby countryside and gives a good understanding of the early industrialisation, including the high chimneys from the spinning and weaving factories of the city. The new railway is not visible from this angle, but the first line was established just the year before and came to be of great importance for the urbanisation of the area. Pencil and tinted drawing by Carl Ludvig Ferdinand Messman. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MHM 002903).

This view of Malmö from 1857 was sketched from the nearby countryside and gives a good understanding of the early industrialisation, including the high chimneys from the spinning and weaving factories of the city. The new railway is not visible from this angle, but the first line was established just the year before and came to be of great importance for the urbanisation of the area. Pencil and tinted drawing by Carl Ludvig Ferdinand Messman. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MHM 002903).Cotton fabrics had, prior to this period, been quite expensive and, at large, been restricted to the well-to-do population, but with the increasing availability of the raw material, it became more and more popular in wider circles of society. It was not only for clothing, as it suited a range of uses within the home. Curtains, carpets, draperies and upholstery fabrics increased in number in apartments or villas of the middle class and gradually in some working-class homes, too. The need for imports of raw cotton packed in bales and possibly, to some extent, ready-spun cotton thread was due to the establishment of a spinning factory and weaving mill for cotton in the mid-1850s. Their production included machine-woven corduroy, moleskin, denim, calicos, etc, which made it possible to sell fabric at more “reasonable prices” than previous. At the same time, this machine-weaving became a competition for the long-lived traditions of hand-weaving in the local rural area.

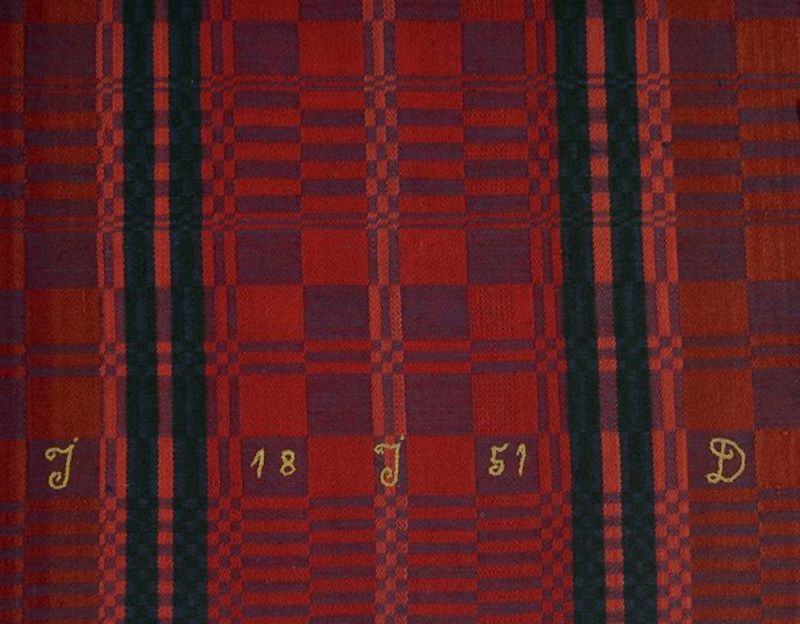

Despite the increasing textile industry with machine woven qualities, the hand weaving continued side by side during many years in the area, though with decreasing importance. This colourful bedcover of cotton warp and woollen weft is one evident example. The interior textile was produced in a home environment and clearly marked “1851” and the initials “JJD” in chain-stitch with silk thread. The unknown female weaver lived in the then rural area Östra Skrävlinge, which today is part of Malmö. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MM 003638, detail of bedcover, 178cm x 134 cm).

Despite the increasing textile industry with machine woven qualities, the hand weaving continued side by side during many years in the area, though with decreasing importance. This colourful bedcover of cotton warp and woollen weft is one evident example. The interior textile was produced in a home environment and clearly marked “1851” and the initials “JJD” in chain-stitch with silk thread. The unknown female weaver lived in the then rural area Östra Skrävlinge, which today is part of Malmö. (Courtesy of: Malmö Museum, No: MM 003638, detail of bedcover, 178cm x 134 cm).Notice: A large number of primary and secondary sources were used for this essay. For a full Bibliography and a complete list of notes, see the Swedish article by Viveka Hansen.

Sources:

- Bjurling, Oscar ed., Malmö stads historia, D. 3, 1820-1870, Malmö 1981.

- Hansen, Viveka, ‘Fyra sekel Malmö textil – 1650 till 2000’, Elbogen pp. 23-91, 1999 (pp. 50-51).

- Kjellberg, Sven T, Ull och Ylle, Lund 1943.

- Malmö Museum, Sweden (Online collection, four images & information – catalogue cards).

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE