ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

THE GREAT EXHIBITION IN 1851

– Textile Influence on a Coastal Town

The Great Exhibition of 1851 displayed, among many other technical inventions, a considerable number of tools and machines that facilitated the preparation of every kind of textile. The Exhibition had enormous influence at the time, and probably made a major contribution to the optimism felt by the population as a whole in response to the industrial progress made in the Victorian period. During my research of textile trades from the small coastal community of Whitby, some connections to the said exhibition were found, which in this short essay will be exemplified through one young tailor and one alum trader who both were included in the official catalogue of 1851.

This is one of two paintings from the finally accepted outlined sketches of Crystal Palace, by the artist William Simpson who illustrated ‘Owen Jones's design for the interior of the Great Exhibition’ in 1850. The colourful atmosphere depending on textile arrangements is among other details concluded as follows by the V&A: ‘The central fabric hangings shown in the William Simpson watercolour never materialised, but they would have complemented the hanging carpets in creating the atmosphere of an eastern bazaar.’ (Courtesy of: Victoria and Albert Museum, V&A, no. 546-1897, Watercolour on Paper, 1850).

This is one of two paintings from the finally accepted outlined sketches of Crystal Palace, by the artist William Simpson who illustrated ‘Owen Jones's design for the interior of the Great Exhibition’ in 1850. The colourful atmosphere depending on textile arrangements is among other details concluded as follows by the V&A: ‘The central fabric hangings shown in the William Simpson watercolour never materialised, but they would have complemented the hanging carpets in creating the atmosphere of an eastern bazaar.’ (Courtesy of: Victoria and Albert Museum, V&A, no. 546-1897, Watercolour on Paper, 1850).In the 1851 census from the Whitby/Ruswarp area, the 25-year-old tailor Luke McHill is listed as – ‘employing 10 men’ in Flowergate. This enterprising young man had already appeared in the 1841 census as a 14-year-old tailor’s apprentice under the name Luke Hill but was never featured in later censuses nor advertised in the Whitby Gazette (introduced 1854). On the other hand, he was an exhibitor at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, where he appeared in the Official Exhibition Catalogue in the ‘Immediate, Personal, or Domestic Use’ section as number ‘107. Hill, L.M. Whitby, Inv. – “Unique habit”, cut out in one piece, and having few seams’. Unfortunately, it has not been possible to discover anything more about his activities, or his exhibiting in London and ten employees of the same year. Nor is there any further information about the appearance of his invention or about how such a pioneering garment was cut.

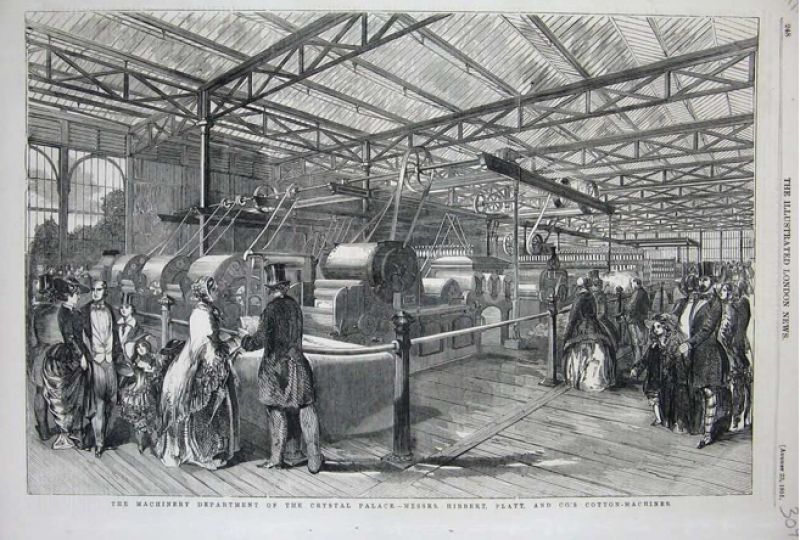

The Great Exhibition was open from 1 May to 11 October and attracted a third of the British population – about six million visitors – presumably numerous people from Whitby also took the opportunity to visit the capital in spring, summer or autumn of 1851. This illustration gives an impression of the exhibited textile machinery as well as the middle-class/wealthy visitors and their fashionable clothing. (Illustrated London News 1851: ‘The Machinery Department of the Crystal Palace – Messrs Hibbert, Platt. and Co's Cotton Machines’).

The Great Exhibition was open from 1 May to 11 October and attracted a third of the British population – about six million visitors – presumably numerous people from Whitby also took the opportunity to visit the capital in spring, summer or autumn of 1851. This illustration gives an impression of the exhibited textile machinery as well as the middle-class/wealthy visitors and their fashionable clothing. (Illustrated London News 1851: ‘The Machinery Department of the Crystal Palace – Messrs Hibbert, Platt. and Co's Cotton Machines’).The official catalogue for the exhibition also listed the Sandsend Alum Works as the seventeenth exhibitor under the heading ‘Chemical and Pharmaceutical Products’ issued for the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, thus providing an opportunity to advertise the many advantages of alum to a wider public: ‘Moberley, W., Mulgrave Alum Works Sandsend, near Whitby, Prod. and Manu. – Raw Alum scale, calcined shale, alum meal and finished alum, Sulphate of magnesia, rough and refined, Ammonia and magnesia, for manure as top dressing.’

A somewhat earlier illustration of the alum works at Kettleness close to Whitby on the Yorkshire coast is evidence of the hard work involved in hacking out alum slate for loading into wheelbarrows, for further transport to basins where the alum would undergo the alum works process. (Aquatint by Georg Walker engraved by Robert Havell, 1814.)

A somewhat earlier illustration of the alum works at Kettleness close to Whitby on the Yorkshire coast is evidence of the hard work involved in hacking out alum slate for loading into wheelbarrows, for further transport to basins where the alum would undergo the alum works process. (Aquatint by Georg Walker engraved by Robert Havell, 1814.)Among many uses, alum had been by far the most common mordant in the dyeing of textiles, being added either before or during the dyeing process. This salt had by no means been alone as a colour fixative for yarn and cloth since a long line of other substances were also used, including iron, potash, tartar, copper sulphate and tin chloride. Several alum works had been active in the Whitby area for a substantial period in the 19th century – Sandsend for almost 250 years, since 1607.

It may be concluded that traces after the tailor Luke McHill ended with the 1851 census and the catalogue of the Great Exhibition of the same year, whilst the Sandsend Alum Works closed their business twenty years later in 1871.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, The Textile History of Whitby 1700-1914 – A lively coastal town between the North Sea and North York Moors, London & Whitby 2015 (pp. 214 & 293-94).

- Illustrated London News, 1851.

- Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) online collection (The Great Exhibition & The Crystal Palaces) & quote and information about Owen Jones’ design (accessed 12/11/2015).

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE