ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

Crowdfunding Campaign

Crowdfunding Campaignkeep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource...

THE STORY No. 5 | FIELDWORK – THE LINNAEAN WAY

Purchases of Cloth and Clothes for Naturalist Journeys

This Essay is part of the long-term research and publicise project

THE STORY | FIELDWORK THE LINNAEAN WAY

Carl Linnaeus and his son, who shared the same name, revealed minute details of their clothing through journals, bills, correspondence, and writings linked to their natural history journeys over a fifty-year period. Carl Linnaeus the Younger’s work as a botanist was comparably modest. Still, due to his father, he had many connections to the extended Linnaean network, particularly after his father died in 1778. However, it is impossible to judge his full potential within natural history as he died at 42, less than six years after his father. Furthermore, these last few years seem to have been the most energetic in his life concerning natural history work and knowledge exchange. He travelled to England in 1781 and to Paris the following year, and maintained correspondence, including the exchange of seeds between naturalists in England, France, North America, Russia, and Sweden. His father, as a young man of 25, made the initial notations of necessary garments during his first provincial tour of Sweden. This will be closely examined with other general observations on the seventeen apostles’ clothes during fieldwork.

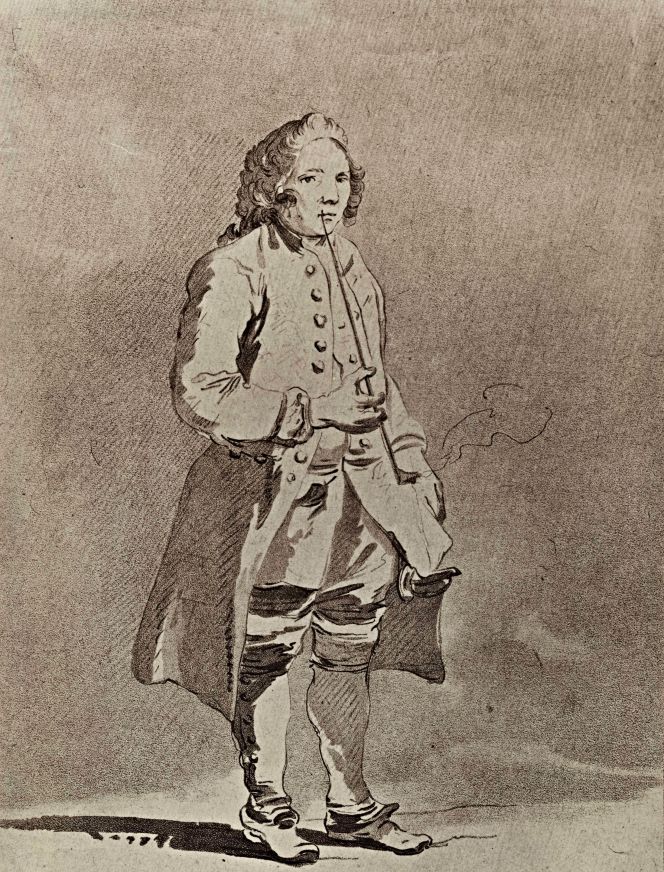

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) was a 40-year-old man in 1747, during the same decade when three of his provincial tours in Sweden took place, financed by the parliament to primarily find improvements for the nation's mercantile economy. This portrait, drawn by the artist Jean Éric Rehn (1717-1793), depicts Linnaeus in his everyday attire. He likely used the same or a similar collarless coat, long waistcoat, breeches, long white stockings and practical low-heeled square-toed shoes during his travels. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, No: 17222/Alvin, copy of original c.1830).

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) was a 40-year-old man in 1747, during the same decade when three of his provincial tours in Sweden took place, financed by the parliament to primarily find improvements for the nation's mercantile economy. This portrait, drawn by the artist Jean Éric Rehn (1717-1793), depicts Linnaeus in his everyday attire. He likely used the same or a similar collarless coat, long waistcoat, breeches, long white stockings and practical low-heeled square-toed shoes during his travels. (Courtesy: Uppsala University Library, No: 17222/Alvin, copy of original c.1830).At the age of 25, Carl Linnaeus himself, already during his first provincial tour to Lapland in 1732, described the importance of his clothing at the outset of the journey on 12 May in his journal (Iter Lapponicum – Lappländska resan):

- ‘The clothes were a small coat of västgötatyg (cloth from Västergötland), without hems with small lapels and a collar of worsted shag. Breeches quite neat of leather. A pigtail wig. A bast-green cap with ear-flaps, a so-called carpus, high boots on the feet. A small case of leather 1/2 ell long, somewhat shorter of width of worked leather, with loops on one side for shutting and hanging up; inside that were put 1 shirt, 2 pairs half-sleeves, 2 night coats, ink-well, a pen-case, microscope, spy-glass. Gauze veil to protect one from midges, notebooks; a pile of bound paper in which to keep plants, both in folio; a comb, my Ornithology, Flora Uplandica and Characteres generica; a hunting knife on one side and a small pistol between my thigh and the saddle; an 8-sided stick on which mensurae have been marked; a wallet in my pocket with a passport issued by the Chancellery of the University of Uppsala.’

This detailed and enlightening account of necessary clothing and equipment was written after his return home, also supplemented with a list of all expenses linked to the journey as financed by the Royal Society of Sciences (Kongl. Wettenskaps Societeten) in Sweden. Prices of cloth, tailor’s wages, etc., give a unique insight into costs during such a natural history journey stretching from 12 May to 10 October in 1732. Below is a translation of the listed garments, along with a few thoughts on purchases made prior to and during the five-month journey.

‘Before the journey itself started, I had to be supplied with necessary clothes, and as I was in some constrained financial circumstances, I chose the most common type of dress:

- 1 Coat, easy to use/walk in the mountains, which could also minimise the use of too many under-garments, of västgötatyg (cloth from Västergötland) with lining, lapels, tailor’s wage, etc. – 10 Daler Silver Coins.

- 1 Cap – 3 Daler Silver Coins.

- 1 pair of leather Breeches for travel – 2 Daler Silver Coins.

I did not include that my own previous clothes had become worn out altogether, such as a blue Coat, Linen garments, and socks, etc. I had high boots with me, but due to the problematic Skul Mountain and other similar places, they broke into pieces, so I had to buy new ones in Härnösand.

- 1 pair of Shoes – 2 Daler Silver Coins & 16 öre.

- 1 pair of Boots in Umeå – 1 Daler Silver Coin.

- 1 pair ditto in Luleå – 1 Daler Silver Coin.

- 1 pair ditto in the mountains – 1 Daler Silver Coin.

- 1 pair ditto in Qvickjock when arriving back – 1 Daler Silver Coin.

- 1 Hat in Kalix – 2 Daler Silver Coins.

- 1 pair of half-boots to use when travelling home in the wet autumn weather – 2 Daler Silver Coins.’

Linnaeus’ detailed account makes it clear that all types of belongings easily became worn out on a natural history expedition in mountainous terrain, and in particular, all types of footwear had to be replaced at regular intervals. Even if clothing amounted to a substantial sum, it was only a small part of the cost of the entire journey, which was 211 Daler Silver Coins. The Royal Society of Sciences assisted with the largest part of the journey’s expenses (c. 133), but still, the young naturalist had some difficulty finding the remaining 78 Daler Silver Coins. Like many other individuals in his strained financial position, he had to find money from several sources to cover ongoing and unforeseen expenses. By using his own saved funds (30), he became ‘relieved’ by a rural dean in Torneå (33), borrowed from Professor Spöring in Åbo (10) and finally owed a burgher in Åbo 5 Daler Silver Coins for repairs made on his saddle. Learned via some correspondence when back home, he received a further 40 Daler Silver Coins from the Royal Society of Sciences, but Linnaeus was still disappointed that he had travelled in the most modest way possible and still had to pay 38 Daler Silver Coins himself.

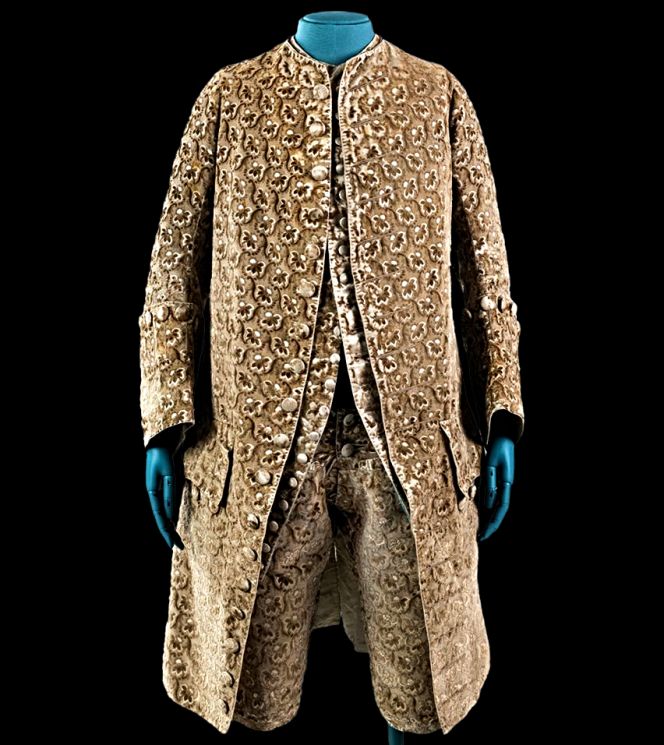

Three-part “habit à la Francaise”. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0105181A-C. DigitaltMuseum).

Three-part “habit à la Francaise”. (Courtesy: The Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0105181A-C. DigitaltMuseum).Carl Linnaeus’ fourth provincial journey took him to Västergötland in 1746, where he met the textile manufacturer Jonas Alströmer (1685-1761) in Alingsås, who once owned the three-part “habit à la Francaise”, illustrated above. It was a fashionable style popular among the elite in Sweden in the mid-18th century. Alströmer was also one of the six instigators of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1739 – so these two men knew each other well from the perspectives of natural history, household economy and in the mercantile spirit of the times, they advocated for fabrics produced in Sweden, stressing above all: the benefits for the domestic economy. However, the costly fabric of this three-part silk velvet habit was probably made in France or England.

While, after his second provincial tour in the province of Dalarna, according to his partly incomplete Foreign Travel journal, he returned to Uppsala and then to Stockholm on 24 November 1734. There, he remained for two weeks, mainly for professional reasons, but he also managed to arrange for some clothes to be made up for him before his impending journey to Holland. Detailed notes were not written about what type of clothes he ordered at the tailor, but they appear to have been made ready within two weeks, after which he returned to Uppsala. He then set off again in the direction of Hedemora and Falun. Here, Carl Linnaeus said farewell to his good friends and was honoured with a number of gifts in January 1735. For instance, he was given ‘beautiful linen garments’ by Mrs Sohlberg, supposedly linen shirts made by herself or other women of her household. It was customary in most areas of Sweden for women to make various linen garments themselves in rural and urban areas. Whilst most people, on the other hand, tended to hand their home-woven or purchased fabrics to the tailors to have their clothes made up according to whatever style was current. The same tradition was followed by Linnaeus, meaning that it was not unusual to receive useful linen garments for free or as a favour (in this case, stitched by the mother of medical student Claes Sohlberg coming along as an assistant on the journey). However, you had to pay a tailor to make breeches, waistcoats, jackets, and so on. Linnaeus’ friend and colleague, Peter Artedi (1705-1735), also met up with him in Leyden some months later, after a visit to London in 1736. Linnaeus’ autobiographical notes give some further indication of the reality of limited means and that some places were more expensive than anticipated: ‘Artedi regretted that his money had been consumed in London’ and that he needed new clothes, books, money for his journey home, etc. Linnaeus seems to have been willing to assist, but sadly, the young man who specialised in ichthyology drowned in Amsterdam the same year.

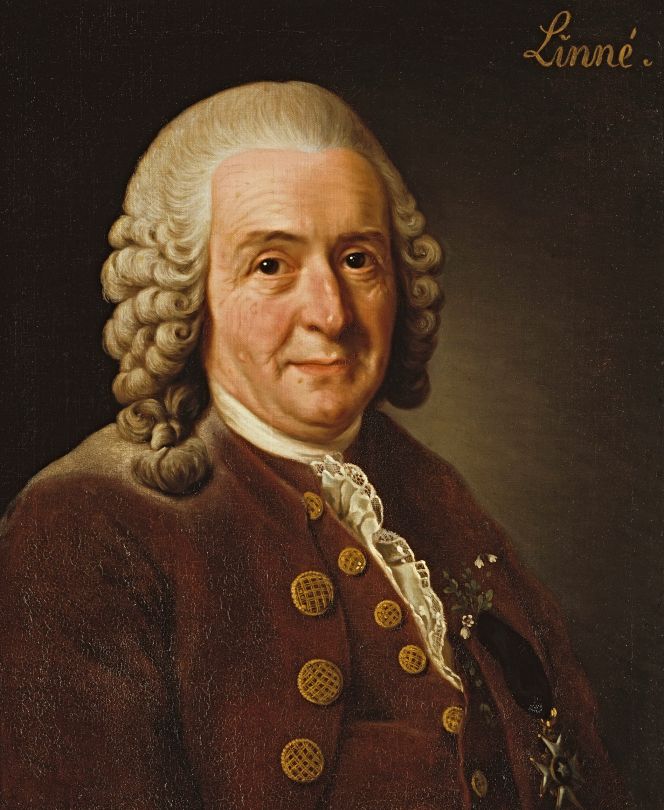

In this oil on canvas by Alexander Roslin (1775), Carl Linnaeus is portrayed relatively late in his life, 26 years after his final provincial tour in Sweden. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden (The National Portrait Collection).

In this oil on canvas by Alexander Roslin (1775), Carl Linnaeus is portrayed relatively late in his life, 26 years after his final provincial tour in Sweden. (Courtesy: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden (The National Portrait Collection).In this portrait, Linnaeus was dressed in a ruffled shirt and probably ‘a frock coat of mixed colours with gilded buttons’ listed under ‘Everyday Clothes’ in the estate inventory three years later. It is evident that, even as an older man, Linnaeus dressed in a coat and waistcoat of a similar cut to what had been fashionable at the time of his wedding, indicating that the fashion changes in men’s formal attire were negligible. Collars and lapels on coats had become common in the 1760s, but, like many other older men, Linnaeus appears not to have adopted that new trend. The same can be seen in Per Krafft the Elder’s painting from 1774, where the bust portrait of Linnaeus shows the clothes in the same style: ‘blue cotton velvet coat with waistcoat ’, judging by the description in the estate inventory.

Close-up detail of a red silk waistcoat dated to 1778. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0044146).

Close-up detail of a red silk waistcoat dated to 1778. (Courtesy: Nordic Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. NM.0044146).Johan Alströmer (1742-1786) was not a former student of Carl Linnaeus himself, unlike his brother Claes, but they belonged to a wealthy Swedish manufacturing family that advocated mercantilism and an economy based on domestic production, founded by their father, Jonas Alströmer. During Johan’s Grand Tour of Europe from 1777 to 1780, he stayed approximately a year in England, from October of the first year of travel, with most months spent in the capital and its surrounding areas. His goals were to learn more about economic matters related to industry and to pursue his interest in natural history. Due to the latter, he is believed to have had frequent contacts with Joseph Banks (1743-1820), Daniel Solander (1733-1782) and others in their network of connections. During this stay in London, Johan, assisted by corresponding relatives, had a tailor create a red silk waistcoat in the spring of 1778 in Sweden. A rare example of a preserved garment, linked to a specific individual, which was useful to add to one’s wardrobe during 18th-century travels as well as at home. This close-up detail shows the skilled tailoring work, including the precise placement of seams, cloth-covered buttons and buttonholes. The Alströmer brothers were not only contemporaries of Carl Linnaeus the Younger, but their visits to London also occurred around the same time.

Carl Linnaeus the Younger (1741-1783) was portrayed at an unknown date, probably in his early twenties. He wears a shirt with front lace ruffles and a collarless coat with shoulder decorations. (Courtesy: Upplandsmuseet, Sweden. No: LIN000179. Sciopticon image of an oil painting. DigitaltMuseum).

Carl Linnaeus the Younger (1741-1783) was portrayed at an unknown date, probably in his early twenties. He wears a shirt with front lace ruffles and a collarless coat with shoulder decorations. (Courtesy: Upplandsmuseet, Sweden. No: LIN000179. Sciopticon image of an oil painting. DigitaltMuseum). However, when Carl Linnaeus the Younger died of jaundice at the age of 42 in November 1783, the preserved estate inventory from him became a detailed source giving proof and examples of several items purchased during his Grand Tour in England, France, Holland and Denmark in 1781-1783, that is to say during the years before his death. The personal items used for his work and clothing purchased abroad were:

- 1 French Gold watch with an English steel chain

- 2 English barber razors with linings

- 1 English penknife with four blades

- 1 English folding rule

- 1 White English coat and waistcoat with spangle buttons

- 1 Grey English coat with a waistcoat with black buttons

- 1 Brown English coat with steel buttons and silk lining

- 1 Fine green English dress coat with steel buttons

- 1 Blue cotton velvet French dress coat

- 1 English woollen coat with wide breeches

This document and a somewhat earlier preserved receipt (kept at The Linnean Society of London) – to ‘Mr Linné’, dated September and December 1781, from ‘Fell. Mayne & Thorne, St Martin’s Lane’ in London – give further clues into clothes and other personal items useful for a well-to-do late 18th century European traveller. The total sum of the tailors’ receipts amounted to £12.0.03/4. This substantial expense, including fine cloths for a dress coat, waistcoat, frock coat, linings, buttons, trimmings, flannel interlinings, furnished pockets and wages for work done, can be compared with his clothing listed as “English” in the estate inventory two years later. An enlightening detail about this trade is that the tailors’ actual work was only valued at £ 2.7sh. 12d or less than 25% of the cost. It is also worth noting that it is somewhat uncertain which garment corresponds to which, as the original receipt was written in English and the estate inventory in Swedish, with various details highlighted. During his time in London, Carl Linnaeus the Younger also visited – most likely quite frequently – the naturalists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander (who died in May 1782), as well as other individuals in their network, to enhance his reputation and knowledge of natural history, being the son of the famous Carl Linnaeus.

Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) also had problems keeping clothing, books etc., dry during his long 18th century sea voyage. On June 12th 1751, towards Java, the final destination was Canton for the Swedish East India ship he mentioned. ‘The sea raged excessively and was driven by the wind, as the snow is on the land. The colour of the waves, and their height indeed, resembled hills of snow. At three o’clock in the afternoon, a great body of water burst into the cabins through the windows and spoiled all the sugar, clothes, books, & etc., which it met with. This accident put us in great confusion. Such was the reception we met with at the rocks of St. Paul and Amsterdam, from whence, the next night, a storm attended with hail so effectually helped us away that the reefed mizzen and foresails only were sufficient, whereas at other times we were obliged to add twenty more sails.'

An 18th century oil on canvas depicting the East India ship at Wampoo, in the river leading up to Canton, comparable to Pehr Osbeck’s journey on an East India ship in 1751. (Courtesy: Sjöhistoriska Museet, Sweden. No. S 3100/part of Canton. DigitaltMuseum).

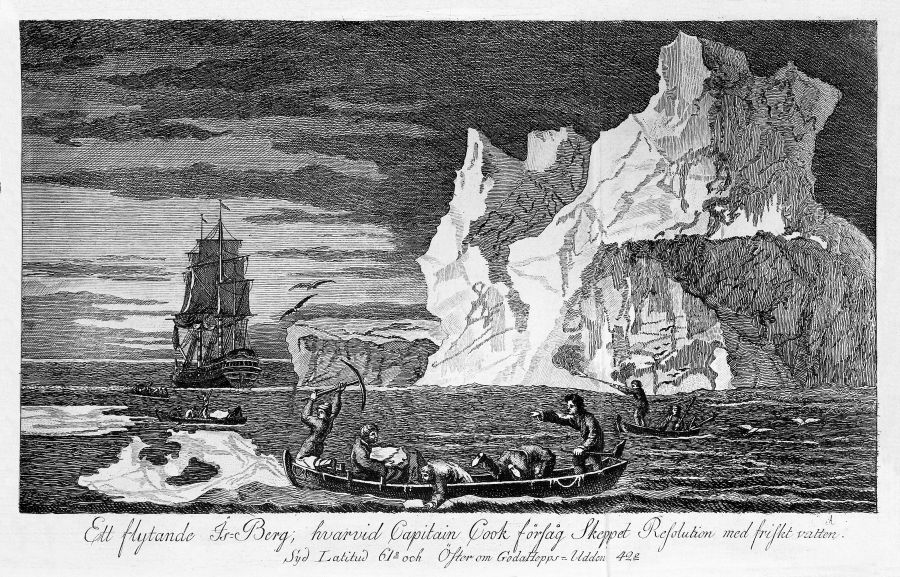

An 18th century oil on canvas depicting the East India ship at Wampoo, in the river leading up to Canton, comparable to Pehr Osbeck’s journey on an East India ship in 1751. (Courtesy: Sjöhistoriska Museet, Sweden. No. S 3100/part of Canton. DigitaltMuseum). ‘A floating iceberg where Cook provided his ship Resolution with fresh water. Latitude 61° south and 42° east of the Cape of Good Hope’, which clearly shows how the crew were dressed while sailing through icy cold waters. (From: Anders Sparrman’s travel journal published in 1802).

‘A floating iceberg where Cook provided his ship Resolution with fresh water. Latitude 61° south and 42° east of the Cape of Good Hope’, which clearly shows how the crew were dressed while sailing through icy cold waters. (From: Anders Sparrman’s travel journal published in 1802).Textile observations onboard generated several reports. Fabrics of varying quality and totally different usage generally played a big part in the ships and their crews’ ability to cope with lengthy sea voyages. It might have been a matter of heat, as when Daniel Rolander (1723-1793), for example, on his way to Suriname in 1755, described a sturdy linen cloth being used as protection against the sun in the scorching heat, or Anders Sparrman (1748-1820) during the second voyage with James Cook (1728-1779), in the Antarctic regions, when extra warm clothing was handed out to the crew. Interestingly, this picture illustrates the same voyage.

The same was noted by Joseph Banks on Cook’s first voyage as they donned their warmest clothes by the Falkland Islands, ‘…myself put on flannel Jacket and waistcoat and thick trousers’ (6 Jan. 1769). Pehr Osbeck wrote that the Swedish sailors wore Danish sheepskin coats in the early 1750s. Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828) experienced what effects a lack of warm clothing could have, as the captain of the Dutch East India Company did not hand out the necessary ration of clothing in 1772, which was thought to have contributed to the calamitous consequences of many fatalities onboard. The ship’s doctor, Carl Fredrik Adler (1720-1761), noted with concern in his patient records in bartering clothes for rations of liquor, went on board a Swedish East India ship in 1753. Whilst Christopher Tärnström (1711-1746), during his East India journey in 1746, pointed out the importance of the quality of the sail cloths for the long voyages of the ships and what strains they had to endure.

However, well the travellers kept their garments from dirt and harmful insects, the fieldwork was tough on the clothes. Daniel Rolander, for example, made several notes on the subject in Suriname: thorny bushes tore clothes to pieces; pockets were useful for fieldwork, handkerchiefs could be used for catching insects; he also stressed the significance of the material of the clothes for the wearer’s well-being in the heat. From western Africa, Adam Afzelius (1750-1837) wrote that it was impossible to dry clothes in the tropical climate during the rainy season, while at the same time Berlin’s travelling companion, Henry Smeathman (1742-1786), gave much good advice for fieldwork to be successful, mainly that: clothes of linen and silk were most suitable in hot countries, but not to forget some sturdy woollen garments for chilly nights, oiled garments for rainy periods, a silk handkerchief to wear around the neck and also long trousers to protect against insects, and the importance of having one ’s feet covered, avoiding long garments in thorny thickets and the great value of mosquito nets. On his northerly journey, Anton Rolandsson Martin (1729-1785) was poorly equipped for the cold; he suffered extreme cold during the three-month-long journey to and from Spitsbergen, and his return journey within Sweden and around its coasts presented him with similar problems. After a lengthy journey in southern Africa, Anders Sparrman described in detail the state of his clothes. At the same time, Carl Peter Thunberg noted that it was difficult to know what clothes would be suitable in such a changeable climate as that of the Cape and, like several others, he had trouble getting his sodden clothes to dry when working in the field. Above all, the travelling accounts, kept by Pehr Kalm (1716-1779), is a unique source of information together with his correspondence during the years after his American journey to the secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Pehr Wargentin (1717-1783), where Kalm continued to specify how torn all his clothes had become, as well as the ones he had originally brought with him and the garments he had acquired along his travels and the costs incurred.

Sources:

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Wästgöta-resa på riksens högloflige ständers befallning förrättad åhr 1746…, Stockholm 1747.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Egenhändiga anteckningar af Carl Linnaeus – om sig sielf med anmärkningar och tillägg, (ed. Adam Afzelius) Stockholm 1823 (pp. 23 & 26).

- Linnaeus, Carl, Linnés Dalaresa – Iter Dalecarlicum, (ed. Arvid HJ. Uggla) Stockholm 1953. (The incomplete Foreign Travel journal in 1735, included in this publication).

- Linnaeus, Carl, Iter Lapponicum – Lappländska resan 1732. Published after the manuscript by Algot Hellbom, Sigurd Fries and Roger Jacobsson. vol. I., Umeå 2003.

- Linnaeus, Carl, Iter Lapponicum – Lappländska resan 1732. Published with notes and registered by Ingegerd Fries and Sigurd Fries. Edited by Roger Jacobsson, vol. II., Umeå 2003. (Notice: clothing only is studied from this list of expenses; for a complete list and comments, see the Swedish quoted list in this book).

- Osbeck, Peter [Pehr], A Voyage to China and the East Indies, 2 vol., London 1771.

- Sparrman, Anders, Resa omkring Jordklotet, I sällskap med Kapit. J. Cook och Hrr Forster. Åren 1772, 73, 74 och 1775…Första afdelningen, Stockholm 1802.

- The Linnean Society of London: Linnean Collections, Manuscripts. Receipt to Carl Linnaeus the Younger [Mr Linné] in 1781, ‘Fell. Mayne & Thorne, St Martin’s Lane’, London].

- Wallin, Sigurd, ‘Urkunder rörande familjen Linnés ägodelar’, Svenska Linnésällskapets Årsskrift 1950-1951, pp. 67-94.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE