ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

THE STORY No. 7 | FIELDWORK – THE LINNAEAN WAY

Writing and Drawing during Naturalist Journeys: Part 1

This Essay is part of the long-term research and publicise project

THE STORY | FIELDWORK THE LINNAEAN WAY

Relevant books to aid with classification work; paper journals kept in a well-protected folder; various paper qualities available for correspondence, collections, and fieldwork; pen and ink or pencils can be traced through several naturalists in the Linnaean network. Pehr Kalm’s travel account may serve as a foundation for knowledge of items purchased along the way on a natural history journey spanning several years. This initial essay on the subject will closely examine the various implements and accessories used for writing and drawing, as recorded by Kalm and other contemporary naturalists. One such artistic example is Sydney Parkinson’s half-finished drawing, presented below as an introductory picture.

Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771) may have aimed to save paint by colouring only part of a sketch, as in this Ipomoea indica found along the Endeavour River in Australia, 1770, and planned to be finished at home. Still, due to his untimely death on board, this had to be finalised by other artists, but it never happened. (Courtesy: Natural History Museum, London…; ’The Endeavour botanical illustrations’ no. 254).

Sydney Parkinson (1745-1771) may have aimed to save paint by colouring only part of a sketch, as in this Ipomoea indica found along the Endeavour River in Australia, 1770, and planned to be finished at home. Still, due to his untimely death on board, this had to be finalised by other artists, but it never happened. (Courtesy: Natural History Museum, London…; ’The Endeavour botanical illustrations’ no. 254).However, it is even more probable that Sydney Parkinson had limited time, as he initially coloured botanical sketches during the journey. Further on, the workload became too extensive when the botanical specimens, etc., were found in more significant numbers, and he had to prioritise. According to research conducted by The Natural History Museum in London, which keeps the drawings: ‘Supervised by Banks, Parkinson made 674 outline drawings on the voyage and 269 finished paintings. John Miller (1759-1796) created 99 finished paintings after the voyage, Frederick Nodder (c.1751-1800) made 272, and three other artists made 114.’ Joseph Banks (1743-1820) also mentioned the intense work in his journal, along the west coast of Australia: ‘This evening we finished drawing the plants got in the last harbour, which had been kept until this time by means of tin chests and wet cloths. In just 14 days, one draughtsman [Parkinson] has made 94 sketch drawings, so quick a hand has acquired by use. The informative note about ‘wet cloths’ offers further insights into the importance of textile materials for the success of their ongoing work. Another outcome from this part of the voyage was that, in total, about 400 plant specimens were collected along the Australian west coast, and seeds from at least six of these plants were cultivated in the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, 1771; one was named Eucalyptus gummifera.

This self-portrait by Sydney Parkinson was made by the young artist during the voyage, sometimes from the summer of 1768 up to his death on 26 January 1771 (Courtesy: Natural History Museum, London).

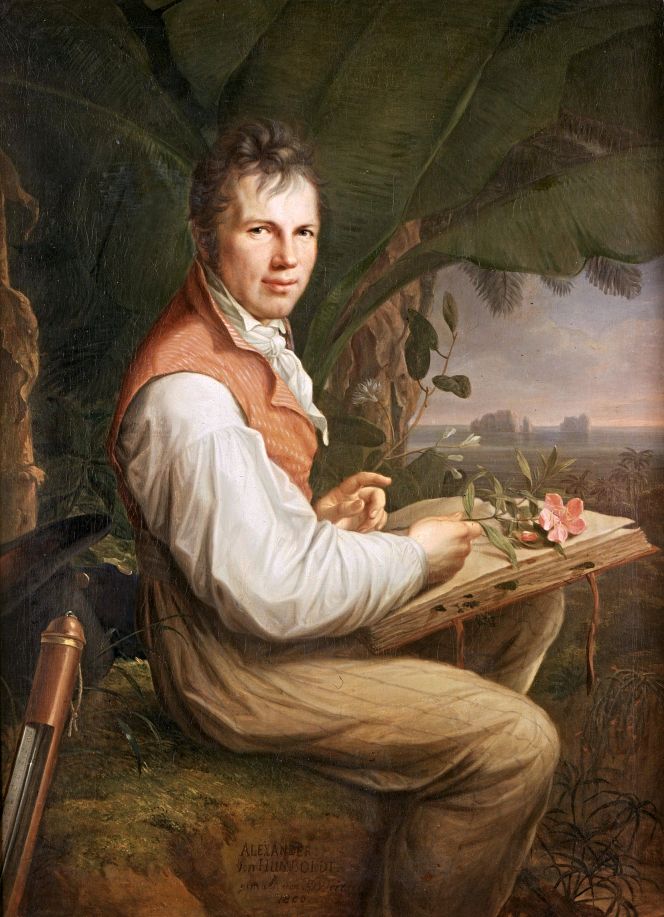

This self-portrait by Sydney Parkinson was made by the young artist during the voyage, sometimes from the summer of 1768 up to his death on 26 January 1771 (Courtesy: Natural History Museum, London). Another connection to Joseph Banks was the naturalist and polymath Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859). In his younger years in 1790, he visited Banks, among others, during his stay in London. Whilst this portrait is an artist's impression of Humboldt during his naturalist studies in South America in the year 1800, examining and making notes of botanical specimens to be pressed in his herbarium book. His field dress consisted of comfortable, loose-fitting striped trousers, a linen shirt, a linen or cotton neckerchief, and a silk waistcoat, in the hot, humid climate. (Courtesy. Alte Nationalgalerie, A II 828. Oil on canvas 1806, by Friedrich Georg Witsch (1758-1828).

Another connection to Joseph Banks was the naturalist and polymath Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859). In his younger years in 1790, he visited Banks, among others, during his stay in London. Whilst this portrait is an artist's impression of Humboldt during his naturalist studies in South America in the year 1800, examining and making notes of botanical specimens to be pressed in his herbarium book. His field dress consisted of comfortable, loose-fitting striped trousers, a linen shirt, a linen or cotton neckerchief, and a silk waistcoat, in the hot, humid climate. (Courtesy. Alte Nationalgalerie, A II 828. Oil on canvas 1806, by Friedrich Georg Witsch (1758-1828).On 14th June 1748, the naturalist Pehr Kalm (1716-1779) listed in his travel account a ‘paintbox to use during travels and a dozen brushes’ to a total of 11Sh.6d. in the month before leaving England for the North American colonies. Whether he or his assistant Lars Jungström (whose lifespan is unknown) used the paint for drawings of botanical or zoological specimens is unknown, as none of such works have been preserved. Judging by Kalm’s otherwise meticulously made observations from all possible perspectives, it is highly likely that such illustrations once existed among his personal herbarium as well as some manuscripts which were destroyed by fire in Turku [Åbo] in 1827. But fortunately, his travel journal was saved: ’The six parts of Kalm’s diary of the journey in the possession of Helsinki University Library, which was saved from destruction in the Great Fire at Turku in 1827 by virtue of being out on loan’ (Kerkkonen, 1959). To give an idea of the importance of his writing tools and his extraordinary diligence, the items listed below suggest that he needed a steady supply of stationery. The original list was written in the tiniest font to save paper.

On several occasions during his travels from Stockholm to Göteborg in Sweden, Pehr Kalm acquired various writing tools, also in Norway and, in particular, in London. It is worth noting that he bought surprisingly few such items during his almost two-and-a-half-year stay in the North American colonies. Perhaps this was due to his uncertainty about the supply of graphite pencils, as the only known large deposit of graphite was in Cumbria (northern England), meaning that all pencils of this sort were traded from England to America in the mid-18th century. Or, if he was aware of this, such pencils and maybe also ink powder – as he purchased ‘3 cones’ prior to the Atlantic crossing – were more affordable in London. It may also have been a combination of both reasons. All these items were probably kept for easy daily access among his personal belongings.

In Sweden – 1747

- 12 Oct. Pencils, 3öre.

- 20 Oct. Ink with a bottle, to keep it in, 9öre.

- 25 Oct. Ruler of boxwood, 18öre.

- 5 Nov. Drawing brushes, 6öre.

- 10 Nov. Pencils, 3öre.

- 18 Nov. Ink, 3öre.

In Norway and Norwegian money, 1747 to 1748.

- 19 Dec. Pencils, 8Shill.

- 9 Jan. Graphite pencils, 6Shill.

In England and English money, 1748.

- 3 March. Graphite pencils, 3d.

- 3 March. Ink, 2d.

- 16 March. Graphite pencils with steel holder, 6d.

- 3 May. Graphite pencils, 6d.

- 21 May. Graphite pencil, 2d.

- 24 May. Graphite pencil with holder, 10d.

- 26 May. A dozen good graphite pencils, 2Sh.6d.

- 27 May. Graphite pencils with brass holder, 1Sh.6d.

- 14 June. Holder for brushes, 1d.

- 15 June. Ink, 1d.

- 25 June. 3 cones of ink powder, 1Sh. 4d.

In America, 1748 to 1751

- 30 Oct. 1749. Pencils, 2d.

- 5 April. 1750. Pencils, 1d.

- 22 June. 1750. Pencils, 5d.

- 8 Nov. 1750. Graphite pencil, 8d.

In England and English money, 1751

- 8 April. Graphite pencil, 4d.

This graphite pencil is a rare survivor of an early model, dating from around 1700 or slightly later. Some of Pehr Kalm’s purchases of pencils were probably of a similar design, featuring a piece of graphite rock carved to a suitable size for writing. While a few of these listed pencils were also fitted with a holder or even a brass holder. (Courtesy: A.W. Faber-Castell Archive, Germany).

This graphite pencil is a rare survivor of an early model, dating from around 1700 or slightly later. Some of Pehr Kalm’s purchases of pencils were probably of a similar design, featuring a piece of graphite rock carved to a suitable size for writing. While a few of these listed pencils were also fitted with a holder or even a brass holder. (Courtesy: A.W. Faber-Castell Archive, Germany).Pencils – either listed as just pencil or graphite pencil – must have been a significantly more effective tool for Kalm than any pen and ink when working outdoors, partly because the writing was faster with a pencil than with a pen, and partially because pencils could also be used without the writing being spoiled by rain, floodwater or other outdoor moisture. In his journal, he further described the advantages of graphite pencils, which he learned during his stay in London on 23 April 1748: ‘Mr Warner told me yesterday that if one writes with a graphite pencil on clean paper and, as soon as one has finished writing, dips the paper slowly in clean water and then lets it dry well, it will scarcely be possible to erase any of what one has thus written with the pencil, but it will adhere to the paper almost as permanently as if it had been written with ink.’ Pen and ink were evidently in use when writing his journal and for correspondence, judging by extant manuscripts. Whilst the pencil holders of various materials were necessary to prevent staining your hands with graphite. Additionally, candles were frequently listed among the purchases in his travelling account, as they were indispensable for his writing tasks during the dark hours of the day.

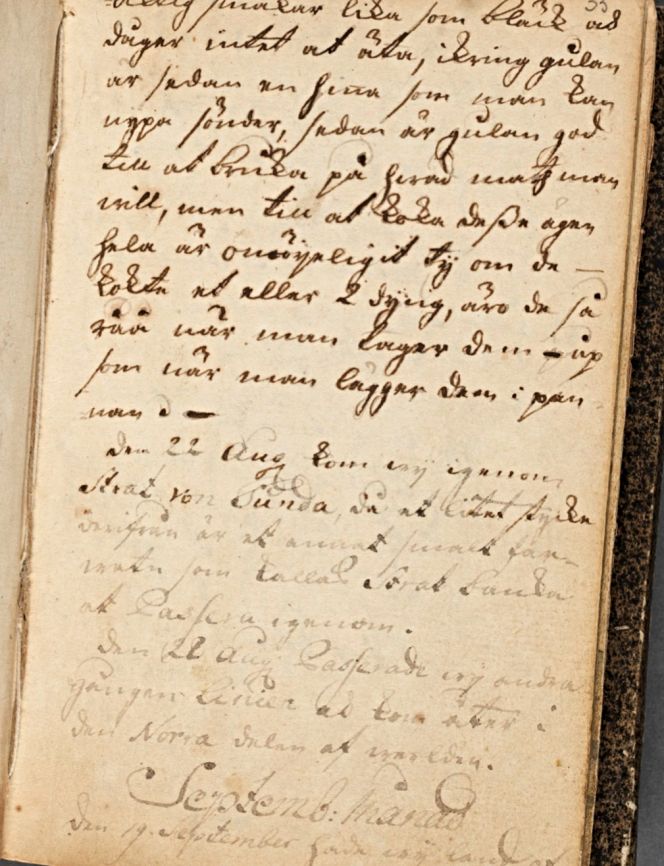

Lack of ink on long sea voyages must have been common, as many onboard used the time to write diaries, logbooks, and letters. Still, such items are rarely identifiable. An exception appears to be the journal of Carl Fredrik von Schantz (1727-1792), kept during a Swedish East India Company voyage that began on 24 August 1746 from Göteborg to Canton, when he was a 19-year-old apprentice for the admiralty. The young man kept a journal with about 15 pages from the period before arriving in Canton, where the ink seems to have been diluted to last longer during the sea voyage. However, there is some doubt whether this ink dilution occurred during the sailing, as the existing handwritten journal is partly a copied, revised version – in his own hand – with the first page showing the return date of ’20 June 1749’ and the introductory image marked with the year ‘1749’. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm: Carl Fredrik von Schantz’s journal. M 292 - 35r).

Lack of ink on long sea voyages must have been common, as many onboard used the time to write diaries, logbooks, and letters. Still, such items are rarely identifiable. An exception appears to be the journal of Carl Fredrik von Schantz (1727-1792), kept during a Swedish East India Company voyage that began on 24 August 1746 from Göteborg to Canton, when he was a 19-year-old apprentice for the admiralty. The young man kept a journal with about 15 pages from the period before arriving in Canton, where the ink seems to have been diluted to last longer during the sea voyage. However, there is some doubt whether this ink dilution occurred during the sailing, as the existing handwritten journal is partly a copied, revised version – in his own hand – with the first page showing the return date of ’20 June 1749’ and the introductory image marked with the year ‘1749’. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm: Carl Fredrik von Schantz’s journal. M 292 - 35r).Schantz was not a naturalist himself, but made a selection of natural history drawings and other watercolour depictions, which are still in pristine condition. These original illustrative materials were inserted as separate plates between the copied text pages in the handwritten journal. One motivating factor for this effort to document in both text and image might have been that on the same ship – Götha Lejon – another young officer, the 18-year-old Carl Johan Gethe (1728-1765), also kept a detailed journal, including watercolours. Together with that, such a ship’s journals, diaries or logs written by scribers/officers/supercargoes onboard were meant to be handed over to the Company for archival purposes after the voyages, which restricted private notes, but seemed to have encouraged illustrative documentation. It is also worth mentioning that several of Carl Linnaeus’ (1707-1778) former students travelled with the same East India Company as ship’s surgeons or chaplains at this time. Christopher Tärnström (1711-1746) voyaged in February 1746, while the young apprentices’ ship set sail in October, Carl Fredrik Adler (1720-1761), 1748-49, Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) left in 1750 and Olof Torén (1718-1753), 1748-49, and in 1750 he also sailed from Göteborg on the next voyage of the Götha Leijon. Some of them may have been inspiring “non-academically educated” young men to take an interest in natural history.

Even if Tärnström set sail the same year as the two young artistic men for Canton, they never met, as he died on Pulo Condore in December 1746. However, in the previous month, Tärnström’s journal gave a hint about how valuable drawings were as a supplement to the written notes of a natural historian. He wrote on 6 November: ‘But what I regretted most was that on such a long voyage I was unable to gather the strange Zoophyta and Lithophyta which were there in substantial quantities, and also the fact that I had nobody who could assist me with making drawings of them…’. Implying either that he was sorry he had not a young man as an assistant capable of drawing these jellyfish and sea acorns, or that such animals very rapidly became putrified in the warm climate of Pulo Condore, and he could not draw quickly enough. A combination of both is also likely as he must have been able to illustrate himself, which he gave several indications of in his two-part journal about a third existing journal on the voyage, named ‘R: B. = Rit-Boken’ (Drawing-Book), including at least 20 drawings, not currently known to exist, as stressed by Kristina Söderpalm (Tärnström… 2005).

References to drawings from natural history journeys no longer seem to exist; perhaps they were lost over the centuries, as drawings and written material were sometimes presented on separate sheets or in separate journals. An example of some thoughts on the accuracy of natural history specimens previously unknown from a European perspective is found in a letter from the naturalist Fredrik Hasselquist (1722-1752), dated Smyrna on 14 November 1751, to the secretary of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Pehr Wargentin (1717-1783). ‘I have the honour to send the attached to My Sir, description and drawing of an Egyptian four-footed animal, unknown to my knowledge within the Zoological History…The painter has not been altogether correct in the depiction; in shape, it is reasonably good, but the main mistake is the fur, which should not be drawn in stripes or clusters as he did, but instead smooth over the entire body. A printmaker of copperplates can rightly correct this.’ It may be coincidental, but this former student of Linnaeus sadly also died in the middle of his natural history mission quite shortly after this letter was written – on 9 February 1752, only 30 years old – and the mentioned drawing was never included in the posthumously published travel journal five years later. However, that has not been the case for all 18th century publications linked to lengthy travels, as other authors succeeded in including plates or sketches in their books.

One example from the perspective of trade is linked to Claes Alströmer (1736-1794), who began his European tour early in 1760. During his travels, he maintained ongoing correspondence with his former teacher, Carl Linnaeus, which lasted over more than four years. He kept him informed about natural history topics, sent seeds, and other items. In 1763, after visiting Portugal, Spain, and France, he stayed in London. During this period, a letter was sent on 11 November to Linnaeus in Uppsala. Alströmer wrote that he, following Linnaeus’ advice, had purchased 78 bird sketches from the naturalist George Edwards (1694-1773). Edwards had travelled in Scandinavia, France, and Holland during his youth, drawing from specimens that were alive, stuffed, or preserved in spirits. He published several volumes, including plates. Alströmer had arranged for the drawings to be shipped via the ship Pelican from London to Samuel Arfvedsson in Götheborg, who would later transport them overland to Linnaeus in Uppsala. There is some uncertainty whether the parcel with the valuable bird sketches ever reached Uppsala, since a letter dated 10 July 1764 from Amsterdam states that Alströmer had not yet received a reply from Linnaeus. Furthermore, the extant letter dated 1 December 1764, written when he was back in Sweden, does not mention this matter either. Additionally, Pehr Kalm, during his stay in London fifteen years earlier, met George Edwards and had the opportunity to carefully examine the drawings, as noted in Kalm’s journal on 22 April 1748.

- ‘In the evening, I was at Dr Mortimer’s, who is secretary to the Royal Society here, to whom I had been invited the previous day; here I met the great ornithologus Mr Edwards, who has published a book on birds in the English language with incomparable copper plates, all in natural colours, and who now showed me drawings of a number of more exotic birds from various places, which he had depicted exceedingly well and intended to issue in print.’

About one month later, in London, Kalm also had the opportunity to visit another traveller who was focused on publishing natural history plates based on his own collection work, sketches and paintings of birds, etc., over an extended period of time. This was the English naturalist Mark Catesby (1682-1749), who also had other contacts within the Linnaean network. He was interested not only in natural history from his home country but also in that from his lengthy stays in the North American colonies of Virginia, Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, as well as Jamaica and the Bahamas Islands – lasting from 1712 to 1719, and a second journey from 1722 to 1726. His publications included descriptions of the areas, their flora, fauna, and inhabitants. Still, the main features were artistically accurate coloured plates of birds, snakes, etc., along with English and French texts side by side. Even if he was a gentleman horticulturist himself, Catesby was not a wealthy man and needed patrons to fulfil his scientific mission. The long-term aims of his collections, writing, illustrating and publishing stretching over several decades were therefore assisted financially by several landowners and merchants in Virginia, subscribers to his forthcoming volumes, Hans Sloane and other associates within the Royal Society, as well as the linen draper, gardener and trader in plants Peter Collinson (1694-1768) in London.

‘Parrot of Carolina on Cypress tree’ shows Mark Catesby’s attention to detail, included in the first volume of The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands… printed in 1731. The preface of his volume also describes his arrival at Charles Town in 1722, his tools, expanding collections, and how he was assisted by Indigenous people: ‘In these Excursions I employ’d an Indian to carry my Box, in which, besides Paper and Materials for painting, I put dry’d Specimens of Plants, Seeds, &c. – as I gather’d them. To the Hospitality and Assistance of these Friendly Indians, I am much indebted…’ | Plate 11 from Catesby, Mark, The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands…1731. (Wellcome Images, London no: L0035347).

‘Parrot of Carolina on Cypress tree’ shows Mark Catesby’s attention to detail, included in the first volume of The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands… printed in 1731. The preface of his volume also describes his arrival at Charles Town in 1722, his tools, expanding collections, and how he was assisted by Indigenous people: ‘In these Excursions I employ’d an Indian to carry my Box, in which, besides Paper and Materials for painting, I put dry’d Specimens of Plants, Seeds, &c. – as I gather’d them. To the Hospitality and Assistance of these Friendly Indians, I am much indebted…’ | Plate 11 from Catesby, Mark, The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands…1731. (Wellcome Images, London no: L0035347).Due to courtesy or modesty some sentences in Catesby’s foreword also doubted his own abilities as a painter, but he also stated that: ‘At my return from America, in the Year 1726, I had the Satisfaction of having my Labours approved of, and was honour’d with the Advice of several of the above-mention’d Gentlemen [Hans Sloane (1660-1653) et al.], most skill’d in the Learning of Nature, who were pleased to think them worth publishing…’ Kalm’s visit took place in Catesby’s later years, and his illustrations were clearly admired by Kalm according to his journal notes on 23 May 1748: ‘I spent the whole afternoon mostly with Mr Catesby, a man who is fairly renowned for his attractive and valuable work, I mean his Natural history of Carolina in America, in which work he has depicted the rarest trees, herbs, animals, birds, fishes, snakes, frogs, lizards, insects in that region incomparably well in life-like colours, so that one can only think that they are alive where they appear in their natural colours on the paper…’ Another somewhat later naturalist and surveyor in the network was Bernard Romans (c.1720-1784), who was interested in the same geographical areas and published A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida in 1776. The ambitious work included more than 300 engravings and descriptions of plants, survey work, the Native Americans’ life, etc.

Sources:

- Beaglehole, J.C. ed., The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks – 1768-1771, 2 vol, Sydney 1963. (Quote: Vol. One. p. 62).

- Catesby, Mark, The natural history of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands… (2 volumes), London 1731 & 1743. (Vol. One: Foreword. pp. VI-XII).

- Cavanagh, Tony, ‘Australian Plants Cultivated in England and Europe from 1771’, Australian Garden History, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Nov./Dec. 1990), pp. 7-10.

- Hansen, Lars, ed., The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby, 2007-2012 (The journals of the Linnaeus Apostles).

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017.

- Helsinki University Library, Finland (Study of Pehr Kalm’s travel diary in manuscript form).

- Kalm. Pehr, Pehr Kalms Amerikanska reseräkning, published by Svenska Litteratursällskapet in Finland, Helsingfors 1956. (Translation & information from listed items related to books, paper, ink, pencils, etc., pp. 17-91).

- Kerkkonen, Martti, Peter Kalm’s North American Journey – Its Ideological Background and Results, Helsinki 1959. (p. 118, Illustration of Kalm’s original journals with information).

- Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm, National Library of Sweden: Two journals: (Schantz…M 292) & (Gethe…M 280).

- Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien, Stockholm. (Quote in translation: Letter from Hasselquist to Wargentin, 14 Nov. 1751).

- Meyers, R.W. & Beck Pritchard, Margaret, ed., Empire's Nature: Mark Catesby's New World Vision, Chapel Hill and London 1998 (pp. 9-13).

- Natural History Museum, London, UK. The Library and Archive Collection (The Endeavour botanical illustrations’ no. 254 & quote from online image source).

- Romans, Bernard, A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida, New York 1776.

- The Linnaean Correspondence. (Letters, L3330, L3427 & L3505 from Clas Alströmer to Carl Linnaeus, 11 November 1763, 10 July 1764 & 1 December 1764. One or more letters from Alströmer sent between July and December 1764 are not known to be extant today).

- Tärnström, Christopher, Christopher Tärnströms journal – En resa mellan Europa och Sydostasien år 1746, edited by Kristina Söderpalm, London & Whitby 2005.

- Wulf, Andrea, Opfindelsen af Naturen: Den eventyrlige beretning om Alexander von Humboldt, videnskabens glemte helt, Denmark 2019.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE