ikfoundation.org

The IK Foundation

Promoting Natural & Cultural History

Since 1988

UNIQUE TEXTILE REFLECTIONS

– Diary kept during a Swedish East India Voyage from 1746 to 1749

Carl Johan Gethe (1728-1765) was 18 years old when he set out on the voyage towards Canton [today Guangzhou] with a Swedish East India Company ship in 1746. He kept a detailed diary and made coloured drawings of various local events, clothing, flora, fauna, coastlines, and more. This personal account, written in a clean copy of his hand, was penned after the journey – as evidenced by the title page, which includes the return date of the voyage – and has survived as a single volume at the National Library of Sweden. In later years, it has been digitised in full. The young man seemed interested in almost “everything” of ongoing life in the diverse coastal societies visited along the route, equally as on board the ship. However, as in many other European travel accounts of the 18th century, his text must be viewed in the context of its time. This essay will examine five watercolours, a selection of quotes from a translation of the original Swedish diary, and some comparable journal notes made by contemporary long-distance travelling Linnaeus Apostles.

In a previous essay about Carl Fredrich von Schantz (1727-1792), who travelled on the same ship as Carl Johan Gethe, it was mentioned that one motivating factor for this effort to document in the text as well as the image may have been that these two young officers inspired each other. The rare circumstance that both documents – clean, copied diaries of their own hands with inserted watercolours bound in volumes from this particular East India voyage – have been preserved to this day makes it even more exciting and informative. Here, Gethe’s illustrated, folded ‘Map of the Archipelago of Canton’ was inserted as a final illustration in the diary. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… Carl Johan Gethe’s journal. p. 213).

In a previous essay about Carl Fredrich von Schantz (1727-1792), who travelled on the same ship as Carl Johan Gethe, it was mentioned that one motivating factor for this effort to document in the text as well as the image may have been that these two young officers inspired each other. The rare circumstance that both documents – clean, copied diaries of their own hands with inserted watercolours bound in volumes from this particular East India voyage – have been preserved to this day makes it even more exciting and informative. Here, Gethe’s illustrated, folded ‘Map of the Archipelago of Canton’ was inserted as a final illustration in the diary. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… Carl Johan Gethe’s journal. p. 213).Moreover, Carl Johan Gethe travelled on the ship Götha Leijon to the East Indies from 1746 to 1749, at the same time as some of the early apostles of Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), who voyaged to the East Indies as a ship’s surgeon or chaplain-cum-naturalist:

- Christopher Tärnström (1711-1746) travelled in February of the same year, while Gethe’s ship set sail in October (initially from Stockholm along the Swedish coast to Göteborg).

- Carl Fredrik Adler (1720-1761) from 1748 to 1749.

- Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) left Sweden in 1750.

- Olof Torén (1718-1753) from 1748 to 1749, and in 1750, he also sailed from Göteborg on the next voyage of the Götha Leijon.

Unlike the Linnaeus Apostles, Gethe did not study at Uppsala University but marked out a military career for himself from a young age. Already as an 18-year-old, he had the opportunity to go to China, thus at an earlier age than the Uppsala students, except the somewhat later born Anders Sparrman (1748-1820), who also undertook an East India voyage at the same age, but as far as is known without keeping a diary. Particularly with Gethe’s youth in mind, his diary is highly comprehensive and well-written. Although there is no mention of textiles from the point of usefulness or the view of desirable dyestuffs that could be brought back home, there are several observations of clothes recorded that show a striking likeness with the reports of the apostles travelling to the East Indies.

Just as on Osbeck’s and Tärnström’s outward voyages, the ship Götha Leijon also victualled at Cadix. In February 1747, Gethe noticed how fashionably the prosperous Spaniards were dressed.

- ‘Men of distinction go dressed as in Sweden as far as clothes fashions are concerned, but gold and silver ornamentation one sees everywhere. The more commoners go about in long, dark brown coats and underneath small waistcoats of several kinds of fabric. Wide-brimmed hats, but the hair is tied up in a loop. The high-ranking Spanish women are rarely seen except in carriages. Then they are without any stiff petticoats, without any headgear other than their own hair pinned and curled and here and there with small posies stuck in. The prosperous ones go mostly dressed in black, without any headgear, and a thin black overskirt which they pull up over the head.’

The traveller also saw the people take part in a religious procession along the streets of the town and wrote, for example, the following on the outfit of the dressed-up Virgin Mary: ‘On top of which the Virgin Mary stood deep in sorrow with tears in her eyes, dressed in a blue cloak with stars of gold sprinkled all over it and a head-cover of the same kind.’ The others in the parade were described in similar terms, making it clear that Gethe found a cascade of various fabrics, silk brocades, golden braids, and magnificent gold and silver. His journey then continued towards the East Indies after a six-week break in Spain.

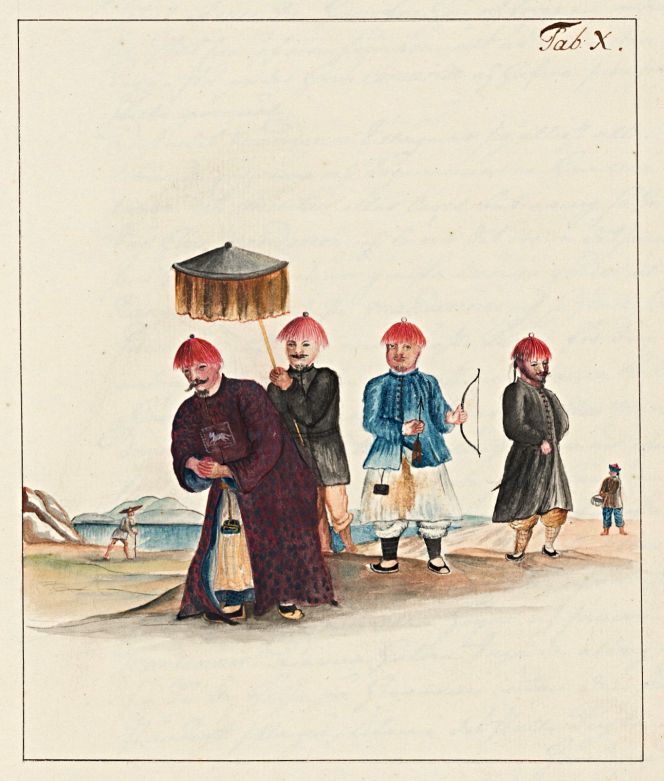

Chinese tradition was depicted in Carl Johan Goethe’s journal. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket…Gethe’s journal. Plate X, p. 96).

Chinese tradition was depicted in Carl Johan Goethe’s journal. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket…Gethe’s journal. Plate X, p. 96).The ship lay anchored at Canton from October 1747 until December 1748, giving him ample time to familiarise himself with the surroundings. He made meticulous notes there concerning the harbour environment, the city’s pulse, customs and traditions, Chinese ships, and the local fauna. Attention was moreover paid to their manner of dressing: ‘All the mandarins use a hat or cap, which is all over covered with a kind of red hanging silk hair, all of which is fixed at the pointed top of the cap and hang down over their eyes; uppermost is a bead which may be of various kinds, merely marking the difference between mandarins of higher or lower status.’ However, some of his further written reflections on local traditions, ceremonies, the roles of men and women, and the use of garments, among other things, mainly came to be assumptions viewed from his European perspective, sometimes in a derogatory manner. Overall, the young man had little knowledge about the complex, long-lived ceremonial events he came to witness through the Buddhist religion, the Lantern Festival, Chinese weddings, and so forth.

The traveller depicted the Chinese costumes in three plates, including drawings of the caps mentioned above. Gethe also included a glossary of common Chinese words and expressions, among which he learnt some terms relating to textile crafts and fabrics, such as:

- byxor [trousers] – kau

- hatt [hat] – måo

- kläde [broadcloth] – tå-lå-jång

- mössa [cap] – måo

- nål [needle] – tiama

- näsduk [handkerchief] – siaokamm

- sax [scissors] – kaotzeun

- segel [sail] – lej

- silke [silk] – sitsao

- strumpor [stockings] – mådd

- skiorta [shirt] – siåmm

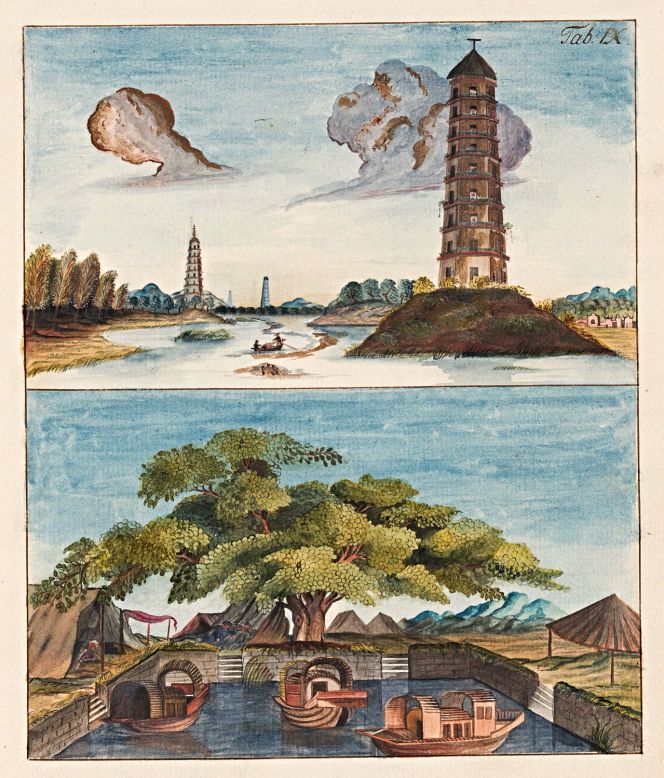

The written text, supplemented by watercolours in Carl Johan Gethe’s journal, in combination with studies of journals kept by Swedish naturalists on East India voyages, often reveals the realities of everyday life for travellers and local citizens alike. This detailed illustration of sailing on the Pearl River near Canton in 1747 is a good example. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… Carl Johan Gethe’s journal. Plate IX/p. 82).

The written text, supplemented by watercolours in Carl Johan Gethe’s journal, in combination with studies of journals kept by Swedish naturalists on East India voyages, often reveals the realities of everyday life for travellers and local citizens alike. This detailed illustration of sailing on the Pearl River near Canton in 1747 is a good example. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… Carl Johan Gethe’s journal. Plate IX/p. 82).Gethe described the large tree among other learned experiences along the river: ‘Just outside the city, you see an indescribably large tree, which by seafarers is named Lazari tree, as everyone having serious illnesses like leprosy, etc., are staying here. This tree has a considerable trunk and a crown measuring 20 fathoms in diameter.’ His depiction and adjoining description of the tree and illnesses is of particular additional interest to the naturalist Pehr Osbeck’s observation of the very same location in September 1751. He noted: ‘The Lazarus tree is further up on the right; it was said that people having leprosy and other nasty diseases lived under this tree, which has very luxuriant branches. Some little inns, which stand several of them close together, somewhat higher up on posts, above the river, make the beginning of the suburbs: before them lie innumerable small and great sampans quite crowded, as well as junks or large Chinese vessels.’

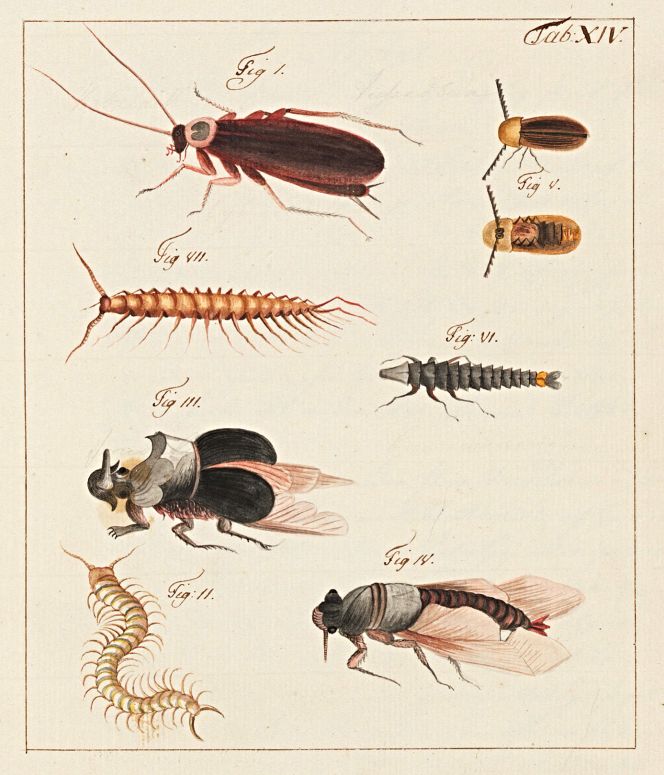

This truthful illustration in Carl Johan Gethe’s journal, originating from his stopover with a Swedish East India Company ship in Canton, shows a selection of troublesome insects from both a practical and a healthy perspective. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… Carl Johan Gethe’s journal. Plate XIV/p. 142).

This truthful illustration in Carl Johan Gethe’s journal, originating from his stopover with a Swedish East India Company ship in Canton, shows a selection of troublesome insects from both a practical and a healthy perspective. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… Carl Johan Gethe’s journal. Plate XIV/p. 142). For instance, the cockroach (Fig. 1) was described in great detail by himself in 1747: ‘A ship can hardly lie in Canton for a month before it is infested by such vermin which multiply most spectacularly. They are normally one breadth of a finger long and can, nonetheless, in marshy places, grow to an inch in length. They are brown-yellow with long feet, enabling them to run extremely fast. Besides, they have wings and fly like dung beetles. A cockroach multiplies in one go with more than a hundred young and is immediately ready to run as fast as the mother. The insect has its uses in that it eats all other harmful insects, but does not spare anything else it might encounter, such as food, clothes, shoes, wood and the human body itself in its sleep, even if somewhat sweaty…’ The naturalist Olof Torén had a similar experience at the same location four years later (Letter VII), where he also pointed out that this species, commonly known as cockroaches in English (Blatta orientalis), is brought to Europe in great numbers via the East India ships.

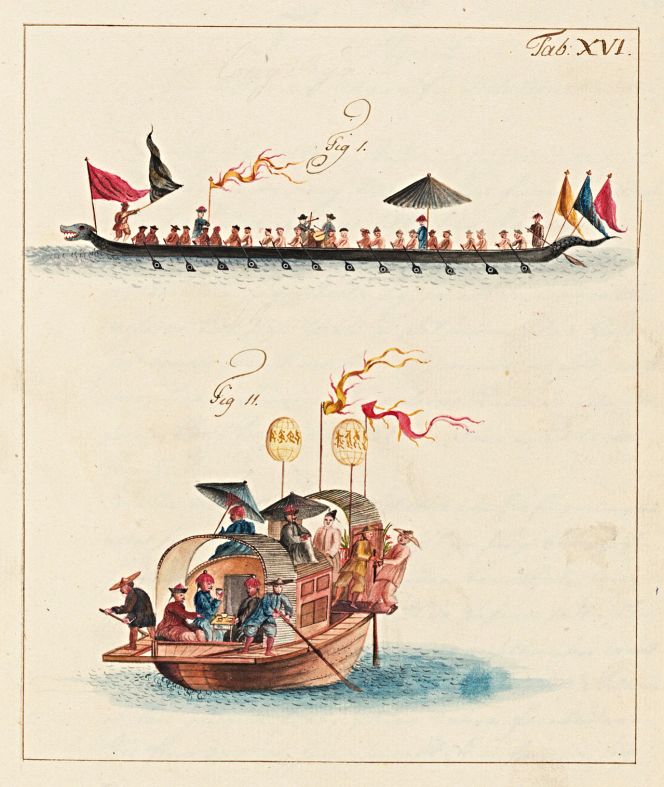

One of Carl Johan Gethe’s watercolour plates also depicted a ‘Long Sampan’ where rowers, drummers, et al. were dressed in either indigo blue coats and trousers with a contrasting red hat or overall more reddish-brown clothing. Equally, details of the local men’s dress had been observed more closely on the smaller ‘Sampan’ boat in Figure II. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… Carl Johan Gethe’s journal. Plate XVI/p. 152).

One of Carl Johan Gethe’s watercolour plates also depicted a ‘Long Sampan’ where rowers, drummers, et al. were dressed in either indigo blue coats and trousers with a contrasting red hat or overall more reddish-brown clothing. Equally, details of the local men’s dress had been observed more closely on the smaller ‘Sampan’ boat in Figure II. (Courtesy: Kungliga Biblioteket… Carl Johan Gethe’s journal. Plate XVI/p. 152).The return voyage to Europe commenced in December 1748 from Canton, when the ship set sail through the China Sea, passing via the Straits of Banca, Sumatra, to Java. There, he, among other matters, noted that the men were only dressed in a loincloth and a cloth wrapped around their heads. After a few days of victualling on Java, the ship set sail towards the Indian Ocean, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, passed St Helena and anchored close to the shore of Ascension Island. Just like for many other East India ships, this place had become an essential stopover along this sea route due to the capture of green sea turtles in the months of March, April, and May, when the turtles lay their eggs on the island. According to his diary, they had managed to take 23 turtles to the ship and ‘one such creature only was enough to feed our entire crew of 130 men.’ On 8 April 1749, the sea voyage continued, passing close to the Canary Islands, and sailed via the English Channel, Dogger Bank, before reaching Göteborg on 20 June of the same year.

Sources:

- Hansen, Lars, ed. The Linnaeus Apostles – Global Science & Adventure, eight volumes, London & Whitby 2007-2012 [Volume Seven: Journals of Pehr Osbeck, Olof Torén and Christopher Tärnström].

- Hansen, Viveka, Textilia Linnaeana – Global 18th Century Textile Traditions & Trade, London 2017 (pp. 448-450).

- Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm, Sweden (National Library of Sweden); Dagbok hållen på Resan till Ost Indien, Begynt den 18 octobr: 1746 och Slutad den 20 Juni 1749’ by Carl Johan Gethe (M 280) | ‘En kort beskrifning uppå en Ostindisk resa till Canton uthi China. Förrättat af Carl Fredrich von Schantz Ifrån åhr 1746 Till åhr 1749.’ (M 292).

- Osbeck, Peter [Pehr], A Voyage to China and the East Indies, 2 vol., London 1771.

- Rydén, Bo, ‘Carl Johan Gethe – Dagbok hållen på resan till Ostindien 1746-1749’, Svenska Linnésällskapets Årsskrift 1975-1977, pp. 51-128 (This article includes more information about Gethe’s diary, a transcription and biography of his life. All in the Swedish language).

- Tärnström, Christopher, Christopher Tärnströms journal – En resa mellan Europa och Sydostasien år 1746, edited by Kristina Söderpalm, London & Whitby 2005.

More in Books & Art:

Essays

The iTEXTILIS is a division of The IK Workshop Society – a global and unique forum for all those interested in Natural & Cultural History.

Open Access Essays by Textile Historian Viveka Hansen

Textile historian Viveka Hansen offers a collection of open-access essays, published under Creative Commons licenses and freely available to all. These essays weave together her latest research, previously published monographs, and earlier projects dating back to the late 1980s. Some essays include rare archival material — originally published in other languages — now translated into English for the first time. These texts reveal little-known aspects of textile history, previously accessible mainly to audiences in Northern Europe. Hansen’s work spans a rich range of topics: the global textile trade, material culture, cloth manufacturing, fashion history, natural dyeing techniques, and the fascinating world of early travelling naturalists — notably the “Linnaean network” — all examined through a global historical lens.

Help secure the future of open access at iTEXTILIS essays! Your donation will keep knowledge open, connected, and growing on this textile history resource.

For regular updates and to fully utilise iTEXTILIS' features, we recommend subscribing to our newsletter, iMESSENGER.

been copied to your clipboard

– a truly European organisation since 1988

Legal issues | Forget me | and much more...

You are welcome to use the information and knowledge from

The IK Workshop Society, as long as you follow a few simple rules.

LEARN MORE & I AGREE