Larry and his wife on the John Muir Trail in the Sierra Nevada.

Forty years ago, in the 1970's, I was doing research in the private family archives of the von Bernstorff family at one of their estates for a book on early 19th Century Germany. Direct archival work, in original manuscripts – letters, diaries and other records – is the detective work of historians. In general terms we know what we are looking for but there are usually many surprises that lie hidden in the materials. In that sense the details as well as the overall setting are your building blocks for description and analysis. It is fundamentally similar in that way to the empirical approach propounded by Carl Linnaeus. This was certainly the case for the story of the writing of my most recent book,

Undying Curiosity: Carsten Niebuhr and the Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia, 1761-1767.

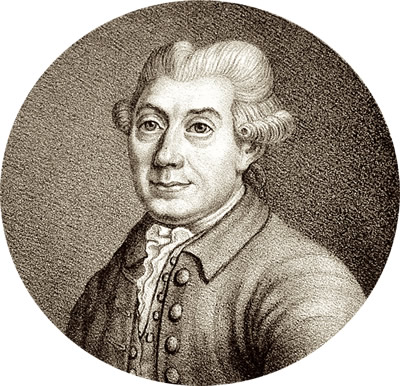

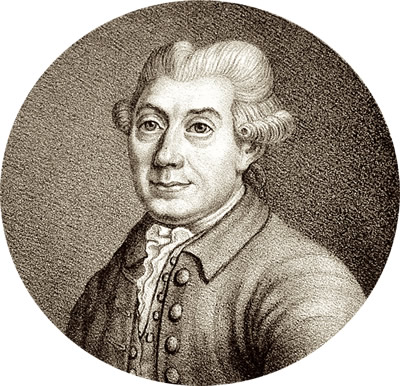

Carsten Niebuhr

Carsten Niebuhr (17 March 1733 – 26 April 1815). Source: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

For three centuries the Bernstorff family had a distinguished record of political and diplomatic service in Hanover, Denmark, Prussia and later a unified Germany. The last politically active member of the family, the diplomat Albrecht von Bernstorff worked to save the lives of Jews persecuted in Nazi Germany, was imprisoned by the Nazis at Dachau and elsewhere, and later executed by the Gestapo just days before the close of World War II for his participation in the German resistance movement against Hitler. While searching through the family papers I found in one chest documents belonging to an early member of the family, Johann Hartwig Ernst von Bernstorff, that contained references to Carsten Niebuhr and an expedition to Arabia in the 18th Century sponsored by the King of Denmark-Norway. Bernstorff was the Danish Foreign minister and was the champion of the expedition in Copenhagen. The reference looked quite intriguing although at that time I knew nothing about the trip. Upon a little investigation I discovered that Niebuhr was the father of the famous historian of Rome, Barthold Georg Niebuhr, and that later after the expedition he became a royal official for the province of Dithmarschen in the town of Meldorf on the North Sea Coast. In the 18th Century Dithmarschen was a territory of the Danish crown, but today is part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. The name Meldorf caught my eye. It was my grandmother's birthplace and the location of her family since the 14th Century. Indeed still today my cousin owns and oversees the family property, a large dairy and grain farm on the coast of the North Sea. My grandmother was born when the area was still part of the Danish Kingdom.

“

Interesting, I thought. I put the few notes I had taken on Niebuhr and the expedition in a folder and filed it away purely out of curiosity.

”

More than thirty years later after retiring from a university career and one in business and public service, I returned to the writing of history. Over the years I had accumulated a number of files on topics that seemed quite promising as research projects. The most slender and nearly forgotten was on Niebuhr and the expedition, but after exploring quite a range of possibilities, the adventures of Niebuhr,

Peter Forsskål and the other members of the expedition emerged as the most compelling and challenging. A multi-year appointment as a Visiting Scholar in the History Department at my alma mater, Berkeley, provided the opportunity for me to begin serious research. Thus began my own journey into the world of 18th Century European scientific exploration, including that of the apostles of Linnaeus, and the lands of the Middle East.

The Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia has been called by the London Times “one of the most extraordinary journeys of all time.” It took me a while before I came to appreciate the basis for that statement. The seven-year long expedition brought together a team of six men – a philologist, a botanist/zoologist, a cartographer/astronomer, a physician, a professional illustrator and an orderly. It was truly a Northern European group – two Danes, two Swedes and two Germans. The team

included as its naturalist, Peter Forsskål, one of Linnaeus' most talented and energetic apostles. Unfortunately, as was not unusual in the experience of 18th century explorers, the expedition was beset by much tragedy. After a little more than three years, Forsskål and four of his colleagues had died from malaria leaving Niebuhr, the cartographer, as the sole survivor of the original team. Nevertheless Niebuhr continued the journey as a solitary explorer, riding his horse or donkey with his instruments and kit, dressed in local clothing, speaking Arabic, and learning and recording an extraordinary amount of information on the diverse peoples and places with which he interacted. By the end of his journey, the expedition as a whole produced a remarkable amount of scholarly information on the Middle East. This included the most complete published description of the flora of Egypt and Southwestern Arabia, and pioneering work in marine biology, especially the first scientific description of the marine life of the Red Sea, all by Forsskål. It provided the most accurate maps and charts of the region produced in the 18th Century, including ones for Yemen, the Nile Delta, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Shatt al Arab and Oman. It yielded the most accurate and scholarly description of the ancient Persian ruins at Persepolis, and invaluable copies of hieroglyphs and cuneiform inscriptions. Niebuhr's work in cultural geography for the areas they visited became the most open-minded and culturally generous description of the Middle East published in the 18th Century. The list could gone on.

Given this multidisciplinary character of the expedition it led me into many different fields of study – some were familiar to me, many were not. They included navigational astronomy, antiquities, cultural geography, paleography and epigraphy, botany, zoology, marine biology, cartography, Middle Eastern Studies, religious studies, the Enlightenment in Northern Europe, biblical philology and many others. Some I had worked in before. As a navigation officer in the United States Navy in the era before GPS, I had done a lot of celestial navigation at sea. I was comfortable with cartography and I had worked on the Enlightenment and in German and Scandinavian history. Exploration, in general terms had been a long standing interest. But, I was not trained in the natural sciences, knew little of philology, and had scant knowledge of Ancient Persia and the significance of Persepolis and other nearby sites. Similarly the Middle East in the 18th Century was a field about which I had only superficial knowledge, and my understanding of its diverse religious and cultural groups was weak. There were other aspects of the project about which I knew little. So I began the adventure of learning a great deal that was new to me. Intellectually I sort of replicated after the fact, and on a very small and secure stage, some of the investigatory experiences of the expedition.

Fortunately, the resources at hand for making such an investigation were rich. They included documentary collections in Copenhagen, Kiel, Göttingen, Berlin and Meldorf – official manuscript records, original field notebooks, personal letters, drawings, maps and charts completed in the field, botanical and zoological specimens, astronomical observations, navigational instruments and the like. The research led me into libraries diverse in their location and focus, from the Royal Library in Copenhagen and the old Library in Göttingen, to my own here at the University of California, Berkeley, and into many specialized libraries. My goodness, the topic was a wonderful platform for learning. Of course, the human side of the project was even more rewarding. Scholars in many countries were extraordinarily generous in sharing their expertise and knowledge. To cite just a few, Ib Friis, who was Professor of Botany at the University of Copenhagen, and Head of the Botanical Museum for the Natural History Museum of Denmark, was of immense help in answering questions and reviewing drafts on Forsskål's work. Friis is the co-author of an updated and analyzed version of Forsskål's

Flora Aegyptiaco-Arabica, the very best study of the work available. Together we went over Forsskål's

Herbarium at the Museum. Professor Dieter Lohmeier, Director of the Schleswig-Holsteinischen Landesbibliothek, was extraordinarily helpful in my exploration of Niebuhr's many manuscript documents.

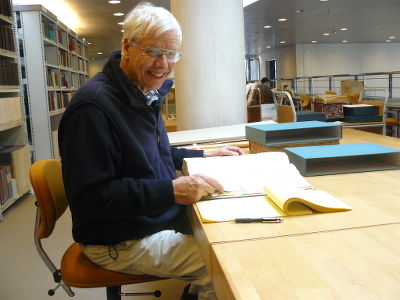

The author working in The National Library of Denmark (Det Kongelige Bibliotek).

Then Josef Wiesehöfer, Professor of Ancient History at the Christian-Albrechts University in Kiel, one of the world's leading scholars on Ancient Persia, shared his knowledge of the expedition and of Niebuhr's detailed work in the ruins of Persepolis and other sites in Iran. Professor Peter Paret, my mentor at Stanford and then Professor of Humanities, Emeritus, at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, an expert in historical analysis and the period of the Enlightenment, examined my drafts with his very sharp, critical intellect, and we had many great discussions on issues of the study. Jürgen Osterhammel, Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at the University of Kontanz, a great scholar on Enlightenment travel and exploration in Asia, very generously critiqued my work; Stig Rasmussen, Head of the Department of Orientalia and Judaica at the Royal Library in Copenhagen did likewise, as did Professor Ira Lapidus, Professor of Middle Eastern History at Berkeley, and a world expert on Islamic Societies. Lars Hansen was of great help regarding Linnaeus, the apostles and specifically the diary of Forsskål, which was published in English as part of his monumental collection on the apostles. I had studied Swedish years earlier as a student, but I had rarely used it and my knowledge of eighteenth century usage was poor. So the availability of the translation was of great help. The list could go on and on. The kindness and generosity of scores of people – librarians, archivists, curators and other scholars was remarkable. My many stimulating and rewarding discussions and communications with them, from which I learned so much, was truly an extraordinarily satisfying part of the project.

In addition, it was wonderful for me to go along with the members of the expedition, after the fact so to speak, through the reading of their personal papers, and to share in their experience of exploration. Exploration has been for me, since childhood, a subject of real interest. On the mantel piece over the fireplace at our family home rested the large, beautiful telescope that Commander Robert Peary, the American explorer, took on his trip towards the North Pole. It still had on it the original canvas wrapping, worn leather lens cap, and rope sling from Peary's trip. My uncle, an engineer in the United States Navy, had connections to the expedition more than a hundred years ago. As a little boy I looked up at that telescope and dreamed about polar exploration. At night I was allowed to go outside and very carefully use it to look at the moon and stars. Growing up I read as much as I could about exploration, especially about the Antarctic. Later, although I mainly focused on other aspects of the history of Germany and Scandinavia, my interest in exploration never left. Moreover, my wife Jane, to whom

Undying Curiosity is dedicated, and I have enjoyed discovery on a miniature scale. We have taken long hikes in different parts of the world together – the famous treks in New Zealand, the Tour de Mt. Blanc around the Mt.Blanc Massif, across the western half of the Pyrenees, through the Dolomites in Italy, across England on the Coast to Coast Walk from the Irish Sea to the North Sea, and the GR5 from Chamonix to Nice, to name just a few. Here in the U.S. we have hiked in the Rocky Mountains, and at home in California we have explored many of the nooks and crannies of the Sierra Nevada Range, including the John Muir Trail. Jane really knows her flowers so it has been like having a naturalist on our trips. Later, I spent a year with the U.S National Science Foundation and went to Antarctica for the annual season. It completed a dream I had of going to the South Pole, where I was able to stay at our scientific station there. I also went over much of Western Antarctica and participated in an expedition to scientifically explore the Ellsworth Range, which includes the continent's highest mountains. What an experience! So I sort of looked at the experience of the Arabian expedition through the lens of our own tromping on trails in various places, my time in Antarctica, and of my work as a navigator in the Navy using one's sextant and tables to find out where we were as we made our many crossings of the Pacific and sailed in other waters.

Finally, it was a great opportunity to deepen the great interest and affection we have for Europe and its languages. With our children and grandchildren we have visited many times. We have so many friends and colleagues there that it is always wonderful to go back. My wife was a Visiting Professor at the University in Aarhus, Denmark, a country for which we have great affection. I first went to Germany almost 60 years ago as an exchange student. We have traveled across the continent from Russia to the Isle of Skye, and from Istanbul to Norway. At the same time I was learning so much that was new to me about the lands and peoples of the Middle East at a time when the region is so very much on our minds, about its history, culture and diversity. That experience was extraordinarily enriching.

So in short, the work of conceiving and writing the book was a terrific learning experience, stimulating in many exciting ways my own curiosity. Thus my experience merely mirrored the character of the expedition itself. The Arabian Journey was a quintessential project of the Enlightenment in Northern Europe manifesting really the remarkable commitment to inquiry of that age. The expedition contributed immensely in an open-minded way to a better understanding of the culture, peoples and ecological domains of the Middle east. Of course working on the book was not a project of true field work, so I do not think that it would meet Linnaeus' exacting empirical standards, but I surely learned a lot in the process and enjoyed crafting an account that shared that learning with others.

Lawrence J Baack spent a year with the U.S National Science Foundation and went to Antarctica.

Carsten Niebuhr (17 March 1733 – 26 April 1815). Source: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Carsten Niebuhr (17 March 1733 – 26 April 1815). Source: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Sveaskog, Stockholm, Sweden

Sveaskog, Stockholm, Sweden